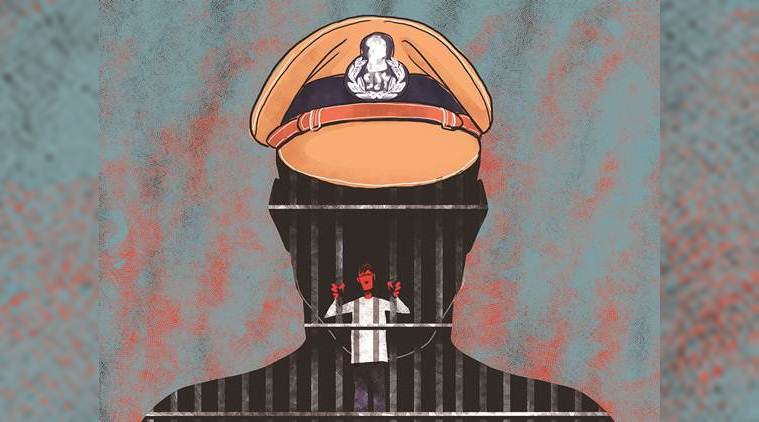

The recent death following alleged custodial torture of P Jeyaraj and his son Bennix in Tamil Nadu has put the spotlight back on the case. (Illustration: Suvajit Dey)

The recent death following alleged custodial torture of P Jeyaraj and his son Bennix in Tamil Nadu has put the spotlight back on the case. (Illustration: Suvajit Dey)

It was the mid-1980s and Calcutta, as it was known then, was witnessing the final phase of the Naxal movement — an armed peasant revolt against the zamindars, which had begun in the summer of 1967 in Darjeeling district’s Naxalbari area. To counter the movement’s violent turn in the 1970s, the State adopted equally violent measures to suppress it. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, newspaper columns were full of reports of Naxal deaths in police lock-ups and staged encounters.

Stories of these custodial deaths, published in The Indian Express, The Telegraph and The Statesman, prompted Justice (retired) Dilip K Basu, then Executive Chairman of the Legal Aid Services of West Bengal and a senior lawyer at the Calcutta High Court and the Supreme Court, to send a letter along with the newspaper clippings to then Chief Justice of India, P N Bhagwati, on August 26, 1986.

Chief Justice Bhagwati, who introduced the concept of Public Interest Litigation to the Indian judicial system, treated the letter as a writ petition, and the Shri D K Basu, Ashok K Johri versus State of West Bengal and State of Uttar Pradesh case was taken up by the apex court in 1987. (In July that year, Johri had written to the CJI over the death of an Aligarh resident, Mahesh Bihari, in police custody.) Senior lawyer Abhishek Singhvi, now a Congress leader, was appointed amicus curiae.

That case led to the landmark order in 1996, known as the D K Basu judgment, on the guidelines to be followed by detaining authorities for any arrest.

The recent death following alleged custodial torture of P Jeyaraj and his son Bennix in Tamil Nadu has put the spotlight back on the case. Justice Basu, who now heads an NGO called the National Committee for Legal Aid Services, recalls, “One day, three men approached me to represent one of their friends who used to be a part of the Naxalite movement but had disassociated himself from it and had been picked up by the police. They said they were not aware of even the police station where he had been taken… I deployed my juniors in different courtrooms, but the youth wasn’t produced in court for three-four days. We eventually found he had been kept in what was a torture house near Alipore (in south Kolkata). I posted some people in a tea stall outside the house and they confirmed they could hear loud cries of pain from inside. I approached the magistrate to order the police to produce him in court.”

After he was brought before court, the man was let off.

Basu says the young man was not alone. Many youths with suspected Naxal links were picked up by the police across the state at the time, a large number of whom were not produced before a magistrate within the stipulated 24 hours, and several ended up dead in “encounters”. Despite two inquiry commissions set up by the Left Front government after it came to power in 1977, the truth of the killings remains unknown. “The commissions submitted their reports but they were never made public,” says CPI (M-L) Liberation leader Abhijit Majumdar, son of the Naxalbari movement leader Charu Majumdar.

As recently as 2014, another inquiry was set up by Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee into the 1971 Cossipore-Baranagar massacre in which reportedly 150 youths alleged to be Naxals or having links with them were killed. Although the report was filed in 2017, it is yet to be tabled in the state Assembly.

Basu, who went on to become a judge at the Calcutta High Court in January 1987, says, “In my letter to the CJI, I underlined the necessity of custody jurisprudence to counter custodial deaths, custodial rape and custodial injury. The police will always claim (any incident of custodial death) as suicide.”

In their order in 1996, Justices A S Anand and Kuldip Singh laid down 11 “requirements” to be followed “in all cases of arrest”. The apex court mandated that the police officer concerned must prepare a memo containing details of the place and time of the arrest, “attested by at least one witness”; inform the next of kin of the person arrested “within a period of 8 to 12 hours after the arrest”; and examine him or her for any injuries and record the same, if requested.

The family members of Jeyaraj and Bennix have alleged that the father and son were remanded in custody despite being visibly injured and bleeding when brought before a magistrate.

Since the D K Basu case, the apex court has issued eight more orders dealing with custodial violence, the last in 2015 on a miscellaneous petition filed by amicus curiae Singhvi, to enforce the implementation of the 1996 judgment. These orders introduced many more guidelines including setting up of state human rights commissions and filling up of vacancies in existing ones.

Justice Basu says that as a judge he went on to deal with many cases of alleged torture. “In my judgments, I directed district judges to carry out surprise visits to police stations, check on individuals held in lockups and find out if the police had registered cases against them and their details.”

However, piecemeal actions are hardly the solution, the 85-year-old says. “If custodial torture has to stop, the D K Basu judgment has to be implemented in spirit.”