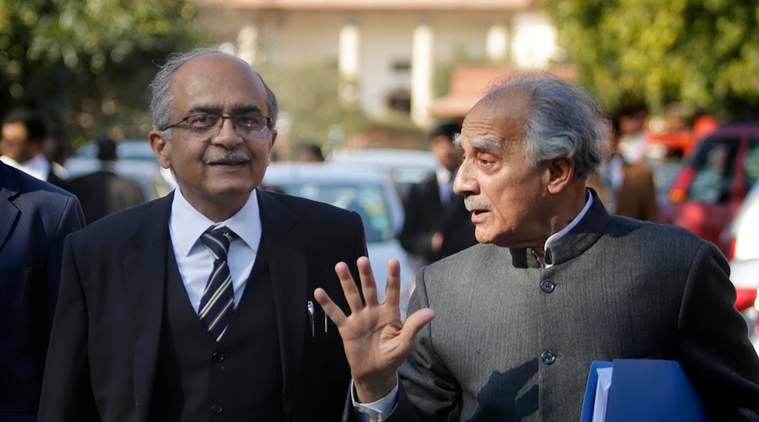

Prashant Bhushan and Arun Shourie. (Express file photo by Praveen Khanna)

Prashant Bhushan and Arun Shourie. (Express file photo by Praveen Khanna)

The challenge to the Constitutional validity of the court’s power to punish for its criminal contempt by advocate Prashant Bhushan and veteran journalists N Ram and Arun Shourie reopens the debate on free speech and “reasonable” restrictions imposed on it.

The centuries-old debate on the law that punishes “scandalizing the court” has been upheld by the courts and invoked frequently. In 1969, a three-judge bench of the SC dismissed a challenge to the law on the grounds that it is an unreasonable restriction on free speech.

Contempt of court is one of the “reasonable restrictions” listed under Article 19(2) of the Constitution on the fundamental right to freedom of speech and expression.

Incidentally, a bench headed by Justice Arun Mishra in two different cases, one involving the Rajasthan disqualification of MLAs and the other, the contempt case against Bhushan, is currently debating the right to voice dissent and restrictions on free speech.

The Supreme Court’s use of powers of contempt started from 1953 in Aswini Kumar Ghose v Arabinda Ghose,where the court said that “if an impression is created in the minds of the public that judges in the highest court in the land act on extraneous considerations in deciding cases, the confidence of the whole community in the administration of justice is bound to be undermined and no greater mischief than that can possibly be imagined.”

A 2006 amendment to the Contempt of Courts Act clarified that the court may punish for contempt only when it finds the speech “is or tends to be substantially interfering with the due course of justice.”

However, the courts have read the provision to make “scandalizing or tending to scandalize” the authority of the court itself a punishable offence regardless of whether it causes obstruction of justice.

Under Article 129 of the Constitution, the Supreme Court derives its powers to punish for its contempt. Similar powers exist for high courts under Article 215. Apart from the jurisdiction to punish for contempt of court, the SC has also invoked Article 142 which gives the court the power to pass any order “necessary for doing complete justice in any cause or matter pending before it,” to punish lawyers for professional misconduct.

Legal scholars have often drawn parallels between criminal contempt of court and the offence of sedition under the Indian Penal Code, which also refers to bringing “hatred or contempt” towards the government.

The SC has narrowly read sedition in landmark rulings, essentially limiting the offence to cases where there is an incitement to violence. However, for scandalizing the court, the SC has widened the offence in a 1996 case to include all acts that “bring the court into disrepute or disrespect or which offend its dignity or its majesty or challenge its authority.”

Although the origins of the court’s power to punish for contempt originates from English law, prominently from a 1900 case R v Gray, Britain has substantially reversed its position. In 2012, its Law Commission recommended the abolition of the offence of “scandalizing the court” which was accepted by the British Parliament in 2013.

The Commission’s report termed the offence “self-serving” and was never intended to protect the “personal dignity of judges” but rather the “integrity of the judicial system.”

“Quite apart from the effect of any actual prosecution, the uncertainty has a chilling effect on expression in general, as a person cannot know in advance whether a proposed statement will fall within the offence,” the report said.

In India, however, a 2018 report of the Law Commission said that the law on contempt needed no change.

“Viewed from the angle of the frequent indulgence of unscrupulous litigants and lawyers alike with administration of justice, it would not be in the interest of litigants and the public at large to minimise the effect of the exercise of powers of contempt as and when the need arises. Therefore, the Commission does not consider it necessary to make any amendment therein for the present,” the 2018 report said.