Picture courtesy: Suvir Saran

Picture courtesy: Suvir Saran

All humans, including refugees who have been dispossessed of their birthplace, are of a certain ethnicity. We might choose to be nomads, or migrants or live in a land far away from our homeland, but our ethnicity never changes. We are born to it, and die being of it.

At 20, I found myself in Manhattan, the financial, cultural and urban epicentre of the United States. Often called “The City” by those who have visited, lived in, or done business there. With its high energy, endless opportunities, and rare ability to help people realise their dreams, it is incomparably cosmopolitan and uniquely ecumenical.

My arrival in New York City made me aware of my ethnicity for the first time. As a college-goer in India, I was routinely confronted with the question, “What are you?” When I answered “I am a human child”, I provoked disgust at my naïveté. And, then, impatience at my unwillingness to accept such questions and their expected answers as commonplace. My questioners, mostly Maharashtrians, were quick to consider me Punjabi or Kashmiri. Some even assumed I was “mixed breed”. Many had no qualms about calling me chikna, code for someone fair, smooth and soft, or even feminine, pretty, or gay. It further needled my questioners when I refused to give my last name. Those familiar with popular American music would accuse me of fashioning myself after Madonna. Truth be told, I was a student of Hindustani classical vocal music. Not even remotely a fan of Madonna. I was also not a fan of being boxed into stereotypes and “isms”.

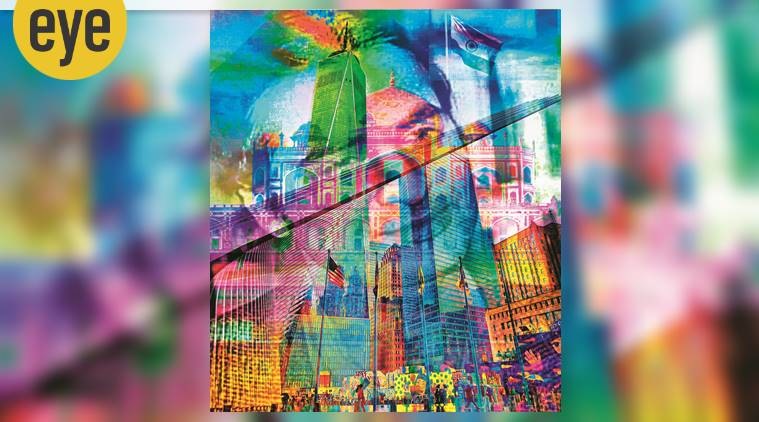

I saw life through a prism of my own making. Monochromatic life bored me. I preferred a colourful way of thinking, living and being. Mumbai was, to my late teen sensibilities, the Manhattan of India. Yet it was New York City where I wanted to study, come of age, and chart the course of my life’s journey. Visiting it in my mid-teens, I saw firsthand the potential of the peerlessly brilliant city. I left it hungry for more. Leaving behind bits and bobs of me waiting to reunite with my soul. Yearning for a sense of home and belonging.

Manhattan was everything I wanted it to be and then some. The people of Manhattan and its boroughs were a unique and interesting lot of humanity. A pool and creed of people for whom all that mattered was their love of a richly diverse city, the plurality driving them to greater heights and keeping them restless in the pursuit of whatever it was that made them tick.

Manhattan had visitors like me coming to it from all around the world. The tourists from lands afar had sensibilities similar to my own. With these foreigners, I had a concordance. Discordance — accompanied by a visceral ugliness — came mostly from small-town Americans. These were the people who asked about my ethnicity and my religious beliefs. They wanted to place me into a stereotypical, formulaic category. In times of communal tensions like 9/11, they were the ones who spat on me, called me racial epithets, and even struck me. Thankfully, these were rare occasions, about a dozen moments in 27 years.

As I make my home in Delhi at 47, I find myself in a city very different from what I left at 18. Delhi is a city of incredible beauty and shocking challenges that come with a booming urban sprawl and industrial growth. I see the hustle and bustle that was New York in 1993, but nowhere near as comfortable with urbanisation as NYC of 2020. I see the glitz and glamour, and I see heart-wrenching poverty. I see cacophonous traffic, and sections of the country still coming of age, struggles similar to the rural outpost where I set up a farm in New York State. Towns and peoples ignored by fellow citizens and country, left behind in the 19th century.

I am shocked to find the food I grew up eating, the regional attire, the architectural sensibilities, the decorative arts — those things from the past that connect me to my birthplace — now considered “ethnic”. Commodities brought into the motherland from nations far, far away are accorded accolades and price points that deify their being. Celebrated for their Northern European provenance, these things are called “food”, “design”, “art”, and “dress”. While what I left behind and returned craving to become one with again is now labeled as “ethnic” — “ethnic clothing”, “ethnic food”, “ethnic art”, “ethnic dress”.

Colonisers long gone, colonies as we knew them done with, the norms of the past ought to be fading away and replaced with happily acceptable and accepted old ways and traditions. When we willingly succumb to Stockholm Syndrome and brand our own social and cultural identity as “ethnic”, we are playing right into the hands of the oppressors. In this moment, one we own and influence, we are furthering the stereotypes and deepening the divides that damage our human collective. When hate is perpetuated and perpetrated, it ends up hating the hater in the end.

I am hoping to see a day when I am simply Suvir. A human being. A day when my food, clothing, art, style and language are simply nouns, with no belittling adjective. A time when they are not reduced to some “ethnic” version of the “norm”, but have a place of pride in their own homeland. The beginning of homeland security.