Shane Warne: The story of Australia great's tough season with Accrington CC

- From the section Cricket

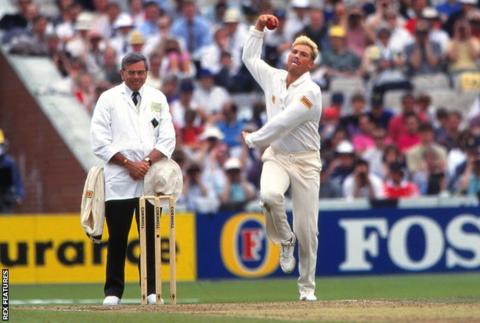

On 4 June 1993, a young Australian leg-spinner called Shane Warne, little known outside his own country, delivered what is widely regarded as the greatest ball in cricket history.

The blond-haired 23-year-old ambled up to the stumps before letting the ball rip towards England batsman Mike Gatting. It drifted in the air, pitching outside Gatting's leg stump, before fizzing past his bat and clipping the off stump.

It was spectacular. It took everyone by surprise. No-one had seen spin like it. With one delivery, Warne had become a household name.

But only two years previously, the same youngster who had just bowled 'The Ball of the Century' was struggling in English club cricket, and was deemed not good enough by Accrington of the Lancashire League.

He hadn't even been their first choice.

Warne was only signed by Accrington as their professional player for the 1991 season because another player pulled out at the last minute.

"We had to sign Shane because we would have been fined by the Lancashire League if we didn't have a pro by the first game of the season," recalls Andy Barker, who was captain at the time. "So, by default, we ended up with Shane Warne."

In the pre-internet age, few knew much about the leg-spinner on his way to Lancashire. On his arrival, many of the players thought the 19-year-old looked like he belonged on a surfboard rather than a cricket pitch, but he fitted in immediately, buying rounds at the bar in the clubhouse.

"He got a lovely warm reception and he liked a beer at the time - he was a young kid," Barker recalls.

But if Warne thought he was in for an easy ride at Accrington he was wrong.

"East Lancashire is the country of the old cotton mill towns. Rainfall is quite high. He did struggle early in the season because the wickets were very wet and it was cold," says Nick Marsh, who opened the batting for Accrington and played with Warne in 1991.

"Coming from Australia, he was used to bowling on wickets that were very hard and flat and here he was bowling on something that was like a pudding in April. If you bowl too short there are good players in the league and they'd just sit back and whack you."

Warne was getting whacked. He wasn't picking up wickets, and he wasn't fairing any better with the bat. Of his first five matches, Accrington lost four.

"The first game, batting at four, I got run out," Warne writes in his autobiography, No Spin.

"The committee called me in and said: 'Listen, the pro never gets run out. You have to learn to turn your back on the bloke and burn him.'

"I argued back, saying the run out was just one of those things and that I wasn't going to be burning anyone. 'No way,' they said. 'The pro doesn't get run out. End of story.'

"I was thrown by this and didn't bowl great. The opposition hammered me. Not a great start."

Things got even worse in Warne's second outing - bowled out first ball against Ramsbottom.

"I watched the stump cartwheel all the way back to the keeper, and as I walked off I heard, 'Go home, pro, you're roobish,' Warne writes.

"I didn't bowl too good that game either. We got smashed and I started to think, 'Jeeeeesus, I should have stuck with footy this winter,'" he continues, in reference to Australian rules football, which he had played at a high level back home.

Barker was in the changing room when Warne trudged in after receiving a mouthful from the locals.

"It really affected him," he recalls. "He said: 'Barks I just don't understand it, I was buying them drinks on Friday night.' I just looked at him and said: 'Welcome to the Lancashire League. In this part of the world, this is Test cricket.'"

Barker decided the youngster needed a bit of a lift, so he and a few senior players took him out on the town.

"He was staying in the house and I said: 'Come on, we'll go out and have a few beers.' I just said I want you to enjoy yourself, just forget it, relax. We had a bit of a 'burster'."

Warne remembers this in his book. "I woke up on Monday morning and gave myself a good hard look in the mirror. 'Grow up, stop larking about and have a crack.'"

Fully settled in and becoming better accustomed to the damper conditions, Warne soon started to show glimpses of what was to come.

"We had a return fixture against Ramsbottom in the cup on the Sunday and he took 6-29. It all changed," Barker recalls.

Warne's leg-spin was beginning to shine. It was too much for most of the batsmen in the Lancashire League to deal with. But his wide array of deliveries was also causing problems for his own team.

Warne would work on signals for his different deliveries with the club wicketkeeper in training - a touch of the right foot to signal a flipper and a scratch of the backside for a googly - but when it came to matches, the keeper would struggle to spot the secret signs.

"You couldn't pick his googly," Barker says. "In one game we had to change the keeper three times and one of them threw his gloves down and said: 'I can't keep to him.' It was a bit embarrassing."

Warne was settling into Accrington life and was well known around the small town. While some overseas players in the past had been a little distant and were quick to shoot off after a game, he would always stick around.

"I was still drinking beer then," Warne writes in his book. "It wasn't until Sri Lanka 1992 that I woke up and got off it. At Accy we had collections for the pro if he scored 50 or a 'Michelle', a fiver-fer.

"They usually amounted to something between 20 and 40 quid and I'd always say, 'Let's put it behind the bar.' I was told that the pros previous to me had kept the money in their pockets and headed back to their digs at the first opportunity, and they loved that I hung around with them and spent it."

Paul Barratt, who played with Warne that season, said the young Australian was a regular feature at the town's watering holes. "If he'd go to the local pubs there would often be a good few people around him. He was a bit of an attraction - it's a small place," he says.

"He had a great sense of humour. He liked a beer, his pizza and his beans on toast. There wasn't a lot of salad and quinoa around at that time."

Marsh adds: "The club gave him a battered old white Ford Escort as his car and it was full of crisp papers, fag packets and beer cans. He liked a Mars bar."

While Warne was proving his ability with the ball, issues with the bat continued all season. In his later years, he turned himself into a handy lower-order batsman, but his time at the crease in Lancashire was usually short-lived.

"His batting was just a nightmare," Barker laughs. "At times he thought he was Viv Richards but he wasn't. He didn't know what a defensive shot was."

Despite having a young man on their books who would go on to take 708 Test wickets, the selection committee at Accrington did not want to keep Warne for a second season. They expected the professional player to chip in with both wickets and runs.

He had finished the 1991 season as the sixth best bowler in the league, with 73 wickets at an average of 15.4. But he scored just 329 runs at an average of 15, making him the 73rd best batsman.

"I told them: 'This kid's going to play for Australia.' They all laughed at me," Barker says. "I said: 'We've got a raw kid here who's just come in, he's 19. If you want my opinion he's worth another punt but if not you'll probably lose him anyway.'"

He was right.

Warne was called up for the Australia B team which toured Zimbabwe in September of that year - 1991. He worked himself up to Australia A and made his Test debut in January 1992 after playing just seven first-class matches. Despite struggling early on against India and Sri Lanka, Warne made the squad for the Ashes tour of England in 1993.

His first ball in the Ashes was the Gatting delivery - the 'Ball of the Century'. Shane Warne had arrived on the global stage.

But the world's best bowler never forgot those who helped him during his tough season in Accrington.

"I remember speaking to him that night because I phoned him up. He said: 'Did you see it?'" Barker recalls. "He just said 'Ah, it was unbelievable. Everything just felt great Barks.'

"He's always kept in contact with everyone. He's an icon - he's up there with Brian Lara and Sachin Tendulkar - but he's still humble enough to remember the people who have been a part of his life, and who may have helped him."