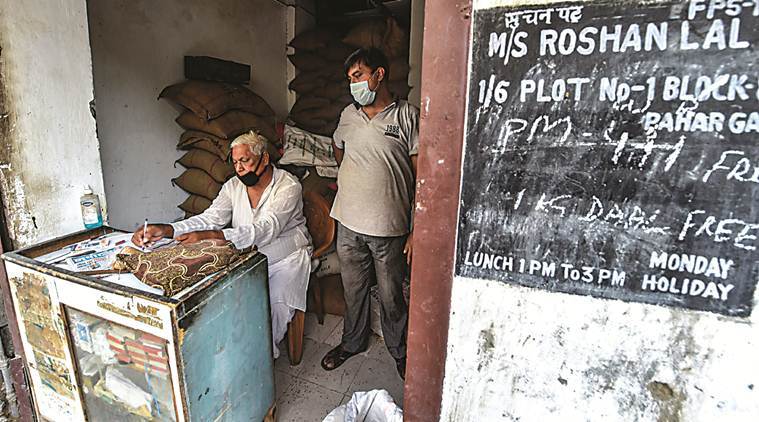

Workers at a fair price shop prepare to distribute ration. (PTI)

Workers at a fair price shop prepare to distribute ration. (PTI)

In the early days of India’s lockdown, stories of food insecurity were rampant. As “Unlock 2.0” progresses, many analysts hope that labour markets will provide the much needed economic resources to the vulnerable. But amidst a range of localised lockdown measures, immediate economic distress continues to persist. The Centre and state governments need to expand the ambit of food transfer programmes and bolster policies that target people most at risk of malnutrition.

There is sound policy that can be built on. The Central government has extended the provision of extra rations of five kg of wheat/rice and one kg of pulses through November, making good use of its abundant grain stocks. Many state governments have stepped in to fill gaps — Bihar’s recent expansion of rations and transfers to school children is one such example. And, a good monsoon points to the potential for bumper crops.

Yet, our analysis of data from several surveys and previous research suggests the persistence of food insecurity, especially among economically and socially disadvantaged groups.

First, even with smooth access to rations, those out of work and with little or no savings will find it hard to cover their households’ full caloric needs. Our research team recently evaluated how Chhattisgarh’s public distribution system functioned through the lockdown and how rural households were faring in the state. Ration shops functioned well: Out of over 4,000 PDS shops we surveyed, 99 per cent were open through the lockdown and stock-outs were extremely rare. Of the over 3,900 households we surveyed in rural Raipur, 95 per cent reported receiving rations. But 20 per cent of the surveyed households worried they would run low or out of food in the coming weeks. Interviews with anganwadi workers revealed that households were eating fewer fruits and vegetables, and more rice and dal than before the lockdown. This is consistent with the NSS data that suggest free rations in Chhattisgarh helped households cover 15 to 33 per cent of their monthly food expenditure, depending on the ration card holder.

Second, distribution of food within households could be worsening both during the lockdowns and under increased economic hardship. With anganwadis shut in many states, daily hot meals for young children have been replaced by erratically distributed take-home dry rations. This change is likely to hit girls hard — substantial inequalities in food consumption within the same household are well-documented. Too frequently, girls and women still eat last at home. Research shows how failing to meet nutritional needs among mothers, potential mothers and young children has long-lasting repercussions on women’s health, morbidity and mortality and the human capital that constitutes the next generation. This type of food insecurity is often invisible, yet can lead to glaring health, cognitive, educational, and wealth deficits in the years to come.

Third, significant gaps in the food security safety net remain for returning migrants. While the prime minister extended two months of rations for eight crore migrant workers in May and June, irrespective of their ration card status, there is no sign that the programme will be continued (although the timeline for distribution was extended). Official data suggest that it remains difficult to get rations to migrants. In April, we began phone surveys of migrants, who were formerly working in urban areas across India. Half of the respondents reported recent food insecurity (eating less than normal). In more recent rounds of surveys in June and July, this share increased to two-thirds. Implementation bottlenecks within the delivery system are further restricting access to food and cash transfers in many areas.

So, how can the Centre and state governments address these concerns?

Like many others, we favour providing food to all who arrive at ration shops seeking it, regardless of identification. Waiting for all systems to be fully operational and online for the One Nation, One Ration Card scheme could cause fatal delays. This is especially critical to ensuring that returning migrant workers without ration cards can access food transfers. In the short-run, it will also ease implementation bottlenecks.

For young children, adolescent girls, and pregnant and lactating women, a period of malnutrition can have lifelong adverse consequences. Identifying ways of maintaining social distancing while reopening anganwadis for essential services (such as vaccinations and hot meals) should be a priority to ensure these individuals, and not just their households, receive food.

Finally, the central and state governments should consider diversifying and expanding products available at fair price shops to help households meet nutritional needs while stabilising local food prices. The short-term introduction of free lentils via the PDS system is welcome. Governments could expand this list to include other essentials such as oil, sugar and locally procured items (such as vegetables and milk). Research has shown that access to rations via PDS helps insulate poor households from food price spikes. Our survey of fair price shops in Chhattisgarh also produced similar results: Prices for chana in private shops in panchayats where PDS shops also stock chana are 10 per cent lower than in panchayats where PDS shops do not stock chana.

India should not allow one emergency — the pandemic — to turn into another. Food security problems are not abating and there are clear steps that should be taken before it is too late.

This article first appeared in the print edition on July 23, 2020 under the title ‘Holes in the safety net’. Pande is the Henry J Heinz II professor of economics and director of the Economic Growth Centre at Yale University, Schaner is assistant professor (Research) of economics at University of Southern California and Troyer Moore is director for South Asia Economics Research at Yale University’s MacMillan Centre