Regular breaks can be an effective way to rebalance your body’s chemistry and regain your sense of control (Illustration: Raúl Soria/The New York Times)

Regular breaks can be an effective way to rebalance your body’s chemistry and regain your sense of control (Illustration: Raúl Soria/The New York Times)

Written by Kiran S & Deepak P

We now live in a world where our phones are our best friends and the most used object every day and it is not surprising that social media has affected our relationships. Global Web Index’s Social Media Trends 2019 report shows that the average daily social media usage of internet users worldwide amounted to 144 minutes per day. According to a 2014 study by Pew Research Center, 42 per cent of couples reported being distracted by their phones, 18 per cent reported arguing over time spent online, and eight per cent reported problems with how a partner spends their time online.

Social Media, Wellbeing and Being “in Control”

According to a survey in 2017 by the Royal Society for Public Health, UK, Britons aged 14-24 believe that Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat and Twitter have detrimental effects on their wellbeing. While the social networks gave them extra scope for self-expression and community-building, the platforms exacerbated anxiety and depression, deprived them of sleep, exposed them to bullying and created worries and “FOMO” (“fear of missing out”). An experiment regarding the Neural Systems Sub-Serving Facebook Addiction by five neuroscientists in 2014 showed that Facebook triggers the same impulsive part of the brain as gambling and substance abuse. Communication expert and author Leslie Shore has observed that fostering relationships online can hurt our relationships offline, and that they can even make us less able to communicate.

Yuval Noah Harari spoke about humans becoming demigods by having control over other species – but are we in control over ourselves? The success of the first societies and civilisations was based on how people interacted with each other and forged relationships – they had a certain level of social intelligence. However, in the era where the persistent power of a mouse click is more important than the universe of shared facts, lesser relationships become the new normal and building strong, deep relationships will take more time and will be more difficult to maintain. Social media gives an illusion of having more social engagements, social capital and popularity masking one’s true persona. Electronic “likes” become more important than a life with friends and family.

The dawn of the previous decade saw the emergence of suicidal games like the Blue Whale Challenge on the internet which claimed innocent lives. Enough discussions have happened about the psychological effects of such games and how it gets into the victims. However, the premise is already prepared by the ever-increasing friendship with social media and more importantly the five inch screens.

The problem is simple – people have more friends on the social media platforms rather than in real life. We rush to see the number of likes on our Facebook and Instagram pages, rather than speak up with your family and friends in person or even on the phone.

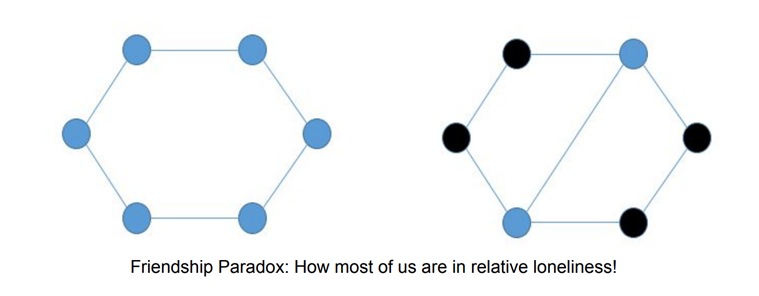

Friendship Paradox: Social Isolation through Social Media

In 1991, Scott Feld, a Professor of Sociology at Purdue University, wrote a paper with a curiously interesting title, “Why Your Friends Have More Friends Than You Do”. His subject of study was real-world friendship networks, not the e-friendships that are created through clicking on a ‘connect’ button on social networks. But, as it sometimes happens in science, the real worth of Scott’s work began to be understood much later. It was in the 2010s, which some of us may rightly recognise as the social network decade, that Scott’s work on what is called the ‘friendship paradox’ started getting noticed.

Apart from relative social isolation, friendship paradox exacerbates other biased patterns to the detriment of users’ mental health

Apart from relative social isolation, friendship paradox exacerbates other biased patterns to the detriment of users’ mental health

The friendship paradox is best understood through a simple visual example. On the left hand side is a perfectly socially egalitarian social network, where each person, represented as a circle, has two friends. Now, let us suppose that a friendship has blossomed between a new pair, leading to the network on the right. Consider any black node in the right figure. She has two friends, but her friends have two and three friends respectively, thus 2.5 friends on an average. Alas, she has less friends than her friends do! If she were the kind of person who would like to be very socially connected, which many of us are, she would find this as a cause of worry. This relative social isolation is true with each black node, which form four out of the six people in the network overall. This is Scott’s theory in action, best summed up by just rephrasing the essence of the title of his paper: “Most people would be less socially connected than their friends”. Real-world social networks have widely non-egalitarian connection patterns, leading to a large majority of people in the network experiencing relative social isolation.

Apart from relative social isolation, friendship paradox exacerbates other biased patterns to the detriment of users’ mental health. Simply consider what we post on social media and what we do not. A visit to a beach is a reason to post on Facebook, but being down with fever is not. Getting promoted in a job is celebrated on LinkedIn, but a failed promotion application is not. A rare culinary success finds a place in Instagram, but none of the vast number of botched cookery experiments make it there. Thus, social media makes us believe that our friends are all having great lives with vacations, job successes and great food. Alas, our own life doesn’t look anything like that! This feeling of misery, much like the friendship paradox, is shared by the vast majority. An increasing number of cases of suicides and self-harm have been linked to social media activity, which often leads us to TV debates as to how they could do that despite their social embeddings in online networks. Scott’s theory may be telling us that the very embeddedness may actually be among the reasons!

Digital Minimalism

The solution to most of these could lie in adopting what Cal Newport, Provost’s Distinguished Associate Professor in the Department of Computer Science at Georgetown University calls ‘digital minimalism’ – minimising the use of electronic devices to a bare need-based minimum – essentially a digital declutter. He says that digital minimalists are the calm, happy people who can hold long conversations without furtive glances at their phones. The over reliance on social media for instant recognition has started affecting the very edifice of humans mastery of this world – the ability to forge relationships. Social networks celebrate virtual relationships. But we have seen the hydra like tentacles popping out to threaten humanity. While complete social media disengagement may be far from feasible in the age of social media, we could try and restrict the time spent on social media, to free up time for other activities. Much like any other addiction, the digital addiction needs to be tapered slowly, not in one go.

Okay, how do we go about it? In this age, every solution comes as an app – not any different for the digital declutter either. The apps have interesting names; AntiSocial, SocialX, Stay Focused, UsageSafe and many others. Many of these enable you to set limits on social media usage, and some even allow you to set limits on specific apps. Let us be the master of the networks too – smartly but surely. May be it is time to listen to the likes of Cal Newport.

Free up some of your social media time to pick up a book, make that call to the old friend you have been looking to connect with, or simply relax and take your time to enjoy your cup of coffee. Next time you are tempted to post your #lockdown photos on Instagram or Facebook and then wait for ‘likes’, hold on. Life will be better without the wait for ‘likes’. After all, humans are not wired to be constantly wired.

Kiran S is an IPS officer. Deepak P is an Assistant Professor in Computer Science at Queen’s University Belfast. His interests are in AI and data ethics.