Inside the “snake museum” at the Nepal Red Cross Snake Bite Treatment centre at Damak, 16 species of snakes are on display. Photo credit: Khem Chandra Adhikari

Inside the “snake museum” at the Nepal Red Cross Snake Bite Treatment centre at Damak, 16 species of snakes are on display. Photo credit: Khem Chandra Adhikari

Sonia Jabbar first learned of the Chaarali Snakebite Treatment centre in Nepal when an employee at the Naxalbari Tea Estate in northern West Bengal was bitten by a cobra two years ago.

With few medical facilities in Naxalbari town equipped to deal with such cases, Jabbar arranged for her employee to be taken to the North Bengal Medical College in Siliguri, approximately 30 minutes away.

“Then her husband came running and said that he did not want her treated here and would take her to a treatment centre in Chaarali. She was fine by evening,” recalled Jabbar.

The Indo-Nepal border as seen from the Indian side at Panitanki. On the other side of the border in Nepal is Kakarbhitta. Photo: Rajib Saha

The Indo-Nepal border as seen from the Indian side at Panitanki. On the other side of the border in Nepal is Kakarbhitta. Photo: Rajib Saha

In the Indo-Nepal border region skirting the states of West Bengal and Bihar, snakebites are common, particularly during the monsoons when the rains flush out snakes, leading to human-wildlife conflict.

The snakebite treatment centre at Chaarali, approximately 15 km from the border near Naxalbari, is well-known to Indians living in neighbouring towns and villages. In fact, it is the preferred medical facility for when a snakebite occurs.

While the approximately 1,751 km long international border between the two countries has several entry points in four Indian states, in West Bengal’s Darjeeling district, Panitanki serves as the main border crossing with an integrated check post that processes the passage of cargo and immigration for travellers.

Snakebite patients in north Bengal use this border crossing to enter Nepal on their way to the snakebite treatment centre at Chaarali.

The patients are usually placed on a motorbike and taken across the border, crossing the bridge across the Mechi river that acts as a natural boundary between India and Nepal. Snakebite patients and their companions do not need passports to enter Nepal.

A challan is provided by Nepali border guards at Kakarbhitta on the other side of the river, who are familiar with the frequent passage of patients from India seeking treatment in Chaarali.

The Mechi river acts as a natural boundary between India and Nepal. A bridge starting at Panitanki allows passage to Nepal on the other side with entry at Kakarbhitta. Photo credit: Rajib Saha

The Mechi river acts as a natural boundary between India and Nepal. A bridge starting at Panitanki allows passage to Nepal on the other side with entry at Kakarbhitta. Photo credit: Rajib Saha

“The border guards prioritise processing their entry requests over other vehicles especially when there is a lot of traffic,” explained Rajib Shaha, 23, a wildlife rehabilitator in Naxalbari who has been researching snakes in the region for four years and has also observed the treatment administered to snakebite patients in Nepal.

A snakebite requires specific treatment administered by trained doctors and paramedics, that is not commonly available in hospitals and medical centres, making centres like the one at Chaarali indispensable for people in the region.

“The treatment for snakebites is not taught in most medical schools in India and Nepal because these schools are based in cities. So when a patient comes with a snakebite, they have to refer the patient elsewhere because they don’t have the treatment,” said Dr. Sanjib Kumar Sharma, Professor and Department Head of Internal Medicine, BP Koirala Institute of Health Sciences in Nepal, who has conducted extensive research on the subject for over 22 years.

The Snakebite Treatment centre at Chaarali was set up by Nepal’s army in 2003, as a field hospital that was later converted into a more permanent structure. Photo credit: Durga Bhattarai

The Snakebite Treatment centre at Chaarali was set up by Nepal’s army in 2003, as a field hospital that was later converted into a more permanent structure. Photo credit: Durga Bhattarai

In 2003, to counter the high prevalence of snakebite cases in the area, the Nepal government set up a field hospital in Chaarali, in southeastern Nepal. Over the years, word spread about the quality of treatment at this hospital through Nepali workers employed in Indian border towns and villages and through Indians working in similar circumstances in Nepal, making Chaarali the prefered treatment centre for snakebite patients.

Treatment in Chaarali

When Hemlal Bhujen, 28, was bitten by a snake three years ago, he was fortunate to have survived. His older brother had died at age seven due to a venomous snakebite some 35 years ago in Tarabari, their native village in northern West Bengal.

Bhujen believes that it was a case of being in the right place because he had been working in Bamondangi, Nepal during the time of his injury and his co-workers knew exactly where to take him for help. “I was working as a construction worker and after I finished at 6 p.m., I went to a nearby house to eat. That was when a gokhro (cobra) bit me,” said Bhujen. He screamed and villagers rushed to help, taking him to Chaarali some 20 kms away on a motorcycle.

Patients undergoing treatment for snakebites at the centre in Chaarali. Photo credit: Durga Bhattarai

Patients undergoing treatment for snakebites at the centre in Chaarali. Photo credit: Durga Bhattarai

“The treatment was good. They gave me saline and a fever came. Then, my head started spinning and I felt nauseous. I had seen the snake that had bitten me and I recognised the species and told the doctor,” Bhujen recalled. His symptoms exacerbated and he was taken into an emergency room—the last thing he remembers.

It took him five days to recover and cost 10,000 Nepali Rupees, a huge sum of money for a daily-wage earner. Arranging for funds to pay medical bills in a foreign country was difficult, but Bhujen borrowed from acquaintances.

He returned to West Bengal and sold his goats and cows to return the money but he does not regret his decision.

“The treatment there was very good and I haven’t experienced anything like it in India. I would have died if I had wasted time coming here,” he said from his home in Tarabari.

Time is key in treating snakebites, explained Dr. Sharma, because the venom causes paralysis, attacking the respiratory system. “So it is crucial that people reach the treatment centre within 30 minutes to an hour after the bite.” However, snakebites by the most common venomous species found in the Indo-Nepal border region, cobras and kraits, occur during nighttime when the person is asleep and is unable to realise that they have been bitten.

“Cobras bite people at dawn or at dusk and kraits bite people at night. Krait bites are usually painless, so people don’t even come to know that they have been bitten,” he said. A substantial delay in identifying that the case involves a snakebite and administering the right treatment are among the leading causes for medical complications, including death, in these cases, according to Dr. Sharma.

There are 84 such centres operating across Nepal now, but only two of these centres are frequently visited by Indian citizens because of their proximity to the border. The second one at Damak in Jhapa district, run by the Nepal Red Cross Society, is approximately 20 km from Gauriganj, a Nepali border town that is the entry point for travellers crossing over from Bairia village in Bihar’s Kishanganj district.

The Nepal Red Cross Snake Bite Treatment centre at Damak is also close to the Indo-Nepal border. Photo credit: Khem Chandra Adhikari

The Nepal Red Cross Snake Bite Treatment centre at Damak is also close to the Indo-Nepal border. Photo credit: Khem Chandra Adhikari

The snakebite treatment centre at Damak was established some 23 years ago and has been receiving Indian patients since it first opened. “Mostly snakebite victims from Kishanganj come to Damak. We don’t have specific data on how many Indians visit, but many come here for treatment,” said Khem Chandra Adhikari, 31, a paramedic at the Nepal Red Cross Snake Bite Treatment Centre. “Word spread through people who work in the border areas.”

Treatment for snakebites at Damak costs 2,250 Nepali Rupees regardless of the patient’s citizenship, an amount that goes into costs involved in running the centre. The anti-venom necessary for treatment is provided for free by the Nepal government.

“The patients are mostly poor labourers and daily-wage workers and many don’t have permanent homes. So those who can’t pay, are given treatment for free after a committee at the institute looks into their economic status. But we can’t do it for everyone because we are reliant on the fees,” said Adhikari. For other patients, treatment is sometimes given at discounted rates.

Damak’s “Snake museum”

A unique feature at Damak is its “snake museum”, a small room in the centre where 16 species of snakes most commonly involved in snakebites in the region, have been preserved and kept on display.

The specimens are used by paramedics and doctors to help patients identify the snake that bit them since many are unable to name the reptile species.

The “snake museum” at the Nepal Red Cross Snake Bite Treatment centre at Damak. Photo credit: Khem Chandra Adhikari

The “snake museum” at the Nepal Red Cross Snake Bite Treatment centre at Damak. Photo credit: Khem Chandra Adhikari

In Chaarali, photographs of snakes are displayed and are used in a similar way. “We analyse cases depending on whether the case is venomous or not depending on the symptoms, but snake identification is important because the public should be able to recognise the different species,” Adhikari said.

Adhikari recalled a case that occurred a little less than two years ago, where a man thought he had been bitten by a non-venomous rat snake. “Some villagers said it still needed to be treated and they brought the patient along with the snake.” It turned out to be a black krait, a venomous species. “It had already been three hours since the snakebite and the symptoms started showing up. He had to be put on a ventilator. So identification of snakes is important,” said Adhikari.

Inside the “snake museum” at the Nepal Red Cross Snake Bite Treatment centre at Damak, 16 species of snakes are on display. Photo credit: Khem Chandra Adhikari

Inside the “snake museum” at the Nepal Red Cross Snake Bite Treatment centre at Damak, 16 species of snakes are on display. Photo credit: Khem Chandra Adhikari

The 25-bed snakebite treatment centre at Chaarali is 16 years old and is jointly run by Nepal’s army, the government and locals. “Most patients from India come between March to August and the army administers the treatment here,” said Durga Bhattarai, 67, chairperson of the Chaarali Snakebite Treatment Centre.

Treatment here can run up to 3,000 Nepali Rupees but like at Damak, it is also administered at discounted rates and sometimes for free if the patients are unable to afford it.

According to figures provided by Bhattarai, last year between March and August, approximately 660 patients visited Chaarali of which 20 involved venomous cases. Bhattarai indicated that there were plans to upgrade the facilities and to acquire ventilators.

Over the years, doctors and paramedics at both Chaarali and Damak have picked up Hindi language skills and speak a mix of Nepali and Hindi when dealing with patients.

Patients undergoing treatment for snakebites at the Nepal Red Cross Snake Bite Treatment centre at Damak. Photo credit: Khem Chandra Adhikari

Patients undergoing treatment for snakebites at the Nepal Red Cross Snake Bite Treatment centre at Damak. Photo credit: Khem Chandra Adhikari

A neglected public health issue

In 2017, the World Health Organization recognised snakebites as a neglected tropical disease and assigned it high priority for large scale action and research.

Research led by Ralph Ravikar published in 2019 indicates that in South Asia, including Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka collectively constitute nearly 70 per cent of snakebite mortality in the world, the region being a biodiversity hotspot for venomous snake species.

In addition, snakebites also cause amputations and other permanent disabilities.

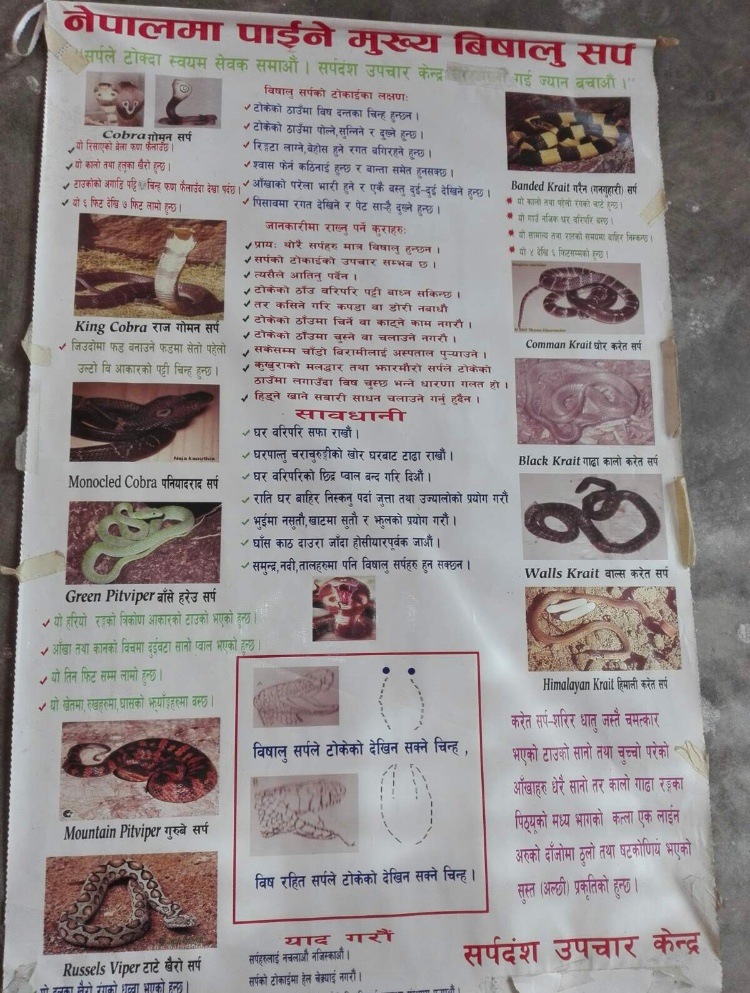

A poster inside the treatment centre at Damak with photos of common snakes in the Indo-Nepal belt to help patients identify the species that bit them. Photo credit: Khem Chandra Adhikari

A poster inside the treatment centre at Damak with photos of common snakes in the Indo-Nepal belt to help patients identify the species that bit them. Photo credit: Khem Chandra Adhikari

Since most snakebite-related deaths occur in rural areas, they aren’t reflected in hospital or government statistics and accurate numbers are difficult to find. However, researchers believe that these numbers are high in South Asia. According to Dr. Sharma, it is a serious issue particularly in the Indo-Nepal belt.

According to Ravikar’s research, nearly 97 per cent of snakebites occur in rural areas and are mostly an agrarian occupational hazard, where treatment delayed beyond six hours can be fatal. With a lack of access to equipped medical centres, in some cases treatment can only be available after as long as two weeks from the bite.

“As a result, 70 to 80 per cent of fatalities happen before patients reach the health facility,” Ravikar writes.

The krait (top left), the rat snake (bottom) and the cobra (top right) are the three most common snakes in the Indo-Nepal belt that cause snakebites. Photo credits: Rajib Saha

The krait (top left), the rat snake (bottom) and the cobra (top right) are the three most common snakes in the Indo-Nepal belt that cause snakebites. Photo credits: Rajib Saha

Experts in India and Nepal believe that long distances to medical centres, a lack of access to transport, little financial resources, a lack of awareness of treatment methods and fear push the rural poor in this region to faith healers known as ‘dhami’ in Nepal and ‘ojha’ in India.

“I do not know exactly what (the ojha/dhami) do, but it doesn’t remove the venom,” said Adhikari. “There is only one treatment for poisonous snakes— antivenom. About 90 per cent of patients say they ‘get well’ after going to a dhami or ojha because they don’t know that they have been bitten by a non-venomous snake,” he said.

Recognising this reliance on faith healers, in 2002, Dr. Sharma and his associates began training the dhami in eastern Nepal on how to recognise venomous bites. “We began training them to understand symptoms like paralysis etc. and to send patients to the centres. So in eastern Nepal these days, you wouldn’t find many dhami or ojha,” said Dr. Sharma.

“People don’t just die of snakebites. A cobra has to inject 15 to 20 mg of venom to kill a healthy patient. Anything less than this will cause (severe) symptoms but not death,” explained Adhikari. The 10 per cent who don’t survive is because of venomous bites and a delay in treatment.

Man-made borders

It is common to see the patients arrive at the centers on a motorcycle, sandwiched between the driver and a companion holding onto the patient for the duration of the journey. This method of transporting patients is the most common and has its roots in the ‘motorcycle volunteer programme’ established in Damak in 2004 that has saved countless lives.

An undated image of a snakebite victim secured between the driver and the companion on a motorcycle, seen here in southeastern Nepal during an operation of the motorcycle volunteer program. According to Dr. Sharma, the patient is not wearing a helmet to ensure “continuous assessment of his state of consciousness by the assistant pillion-rider during transport.” Photo credit: Dr. Sanjib Kumar Sharma

An undated image of a snakebite victim secured between the driver and the companion on a motorcycle, seen here in southeastern Nepal during an operation of the motorcycle volunteer program. According to Dr. Sharma, the patient is not wearing a helmet to ensure “continuous assessment of his state of consciousness by the assistant pillion-rider during transport.” Photo credit: Dr. Sanjib Kumar Sharma

Dr. Sharma explained that the programme was focussed on developing a network of motorcycle owners who would volunteer to transport snakebite patients to the Damak treatment centre, regardless of the time of day, as quickly as possible.

The first volunteers were a group of four villagers with their own vehicles, vetted by the local district vehicle registration office, who would receive recognition for their work and fuel costs for the day.

The programme was successful and variants of it began to be implemented across the border when patients from rural India began coming in using this method.

When Adhikari started working at Damak some 13 years ago, approximately 1,300 snakebite cases would be registered at the centre every year. “We do not have exact numbers but we had at least 100 cases from India on an average.” These days, during the peak season, the centre registers approximately 60 patients from across the border.

The entry point at Panitanki to the bridge over the Mechi river, that travellers need to cross into Nepal. Photo credit: Rajib Saha

The entry point at Panitanki to the bridge over the Mechi river, that travellers need to cross into Nepal. Photo credit: Rajib Saha

The centres at Chaarali and Damak operate 24 hours a day, seven days a week, accessible even now, when coronavirus has forced international border closures.

The Indo-Nepal border crossing at Panitanki-Kakarbhitta closes every night at 8 pm and opens the next morning at six, but an exception is made only for snakebite patients who are ushered into Nepal.

“Humanity does not know borders. They are all man-made,” said Dr. Sharma. With India and Nepal’s diplomatic relations at a particular low over recent territorial disputes, this border crossing has become even more significant for ordinary citizens on both sides of the border.