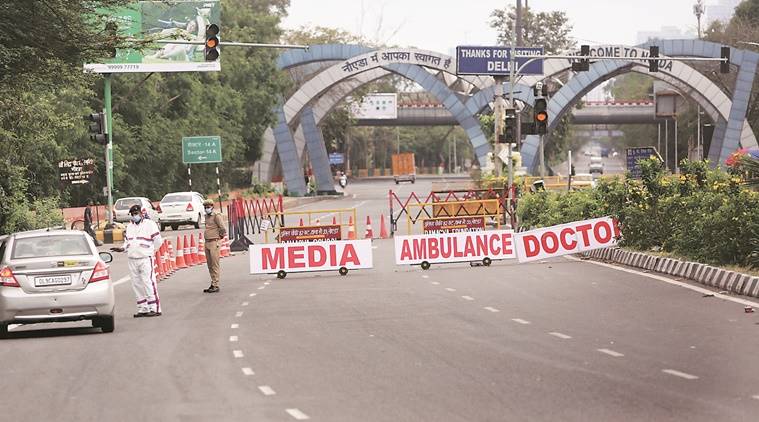

At the Delhi-UP border in Noida. (Photo: Abhinav Saha)

At the Delhi-UP border in Noida. (Photo: Abhinav Saha)

Borders have not been so nebulous, and yet so firmly drawn, as in the past three months.

A virus that originated in China, travelled with people, along with their passports and visas, to distant parts of the globe and became a world-wide pandemic. A cyclone in the eastern Indian Ocean devastated coastal regions in India and Bangladesh, two countries separated by a border for over 70 years. Locusts, benefitting from a freak confluence of multiple climate events in the Indian Ocean region (leading to torrential rains in the Middle East and north African regions in 2018), have swarmed over India and Pakistan, the warring off-spring of an ill-fated Partition in 1947.

On the other hand, nations and regions have firmed up their boundaries, to prevent and regulate movement of people and goods across nationally and internationally recognised territories. This irony cannot have been more poignant anywhere than in India, a country forever in motion. As technology has made it easier to travel across city, state or national boundaries, cities, states and nations have used physically marked and fenced boundaries, documentation and surveillance, to make border crossings as difficult as possible.

In these months, regimes of boundaries have multiplied and become visible in ever shrinking domains of cities, townships, localities, and finally, housing societies, with each promulgating a different set of rules. Each one of these has attempted to prevent access to ones suspected of being carriers of the virus through emergency rules and regulations. This has disrupted connections of employment, health care, education and sociality in cities otherwise intrinsically connected by growing metro rail networks, for example Delhi, Noida, Ghaziabad, Gurugram and Faridabad. Strict imposition of state boundaries during and after the lockdown by Delhi, UP and Haryana left those working across state borders without access to work, and therefore incomes. This included health practitioners living and working across the borders.

In the Delhi-NCR region, state boundaries normally go unnoticed by people who cross them every day to go to work, study, shop, get medical attention in three different states. Similar examples exist in other parts of India, where, but for administrative markers, it is difficult to guess which side of state boundary could a village or town belong to. Borders disrupt historical, social, cultural and emotional relationships between people who can hardly be differentiated from each other, if it were not for the documentary identities that they carry. However, in modern state-systems, rights as citizens/residents get defined through documentary proofs that entitle citizens/residents with access to state benefits. In doing so, they end up creating separate categories of residents, who despite accessing the same borderlands on daily basis, get divided when it comes to access to administratively defined benefits. For example, a resident of Delhi, while possessing all documentary proof required for a domicile in Delhi, gets debarred from applying to 85 per cent Delhi state quota, if she passes the qualifying exam in UP or Haryana even while living in Delhi.

While pre-modern empires in India and other parts had a general sense of their territories, their internal and external borders were not very clearly defined. Frontiers existed as borderlands where multiplicity of jurisdictions led to complex understandings of sovereignty. Borderlands were zones of possibility which allowed their residents to access more than one region. However, with the emergence of colonial state, cartographic anxiety took over, requiring regions to be mapped and marked with exactitude as legal spaces with clarity of jurisdictions and rights. Post-colonial India redefined internal boundaries in reorganisation of states several times over. These include linguistically reorganised states as a result of the State Reorganisation Act, 1956, as well as the reorganisations that followed like Maharashtra-Gujarat and Punjab-Haryana-Himachal in the 1960s, North-eastern states in 1971, Uttarakhand, Jharkand, Chhattisgarh and Delhi in the 1990s, and Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh in 2019.

While the redefined states are viewed as self-defined entities with internal coherence, there remain several internal conflicts within states which challenge the assumption of coherence. The idea of Harit Pradesh, for example, emphasises on socio-cultural continuities with parts of Punjab and Haryana, than Uttar Pradesh that it currently is part of. Therefore, it is clear that state boundaries are not cast in stone, and nothing prevents newer boundaries from being drawn in future.

While in the premodern contexts borderlands were often uninhabited, hostile geographies, the expansion of agrarianism and urbanism has ensured that state and district boundaries are very often densely populated sprawls. In case of ever expanding metro cities, the sprawl often crosses district and state boundaries with special industrial and economic zones, as well as sub-urban housing complexes located in multiple jurisdictions placed in close proximity to each other. This leads to the creation of new borderlands connected through expanding transport networks, with people living in one state and working in another. These borderlands have their own challenges, particularly in the matters of maintaining law and order, as well as with regard to access to state specific benefits.

In India, central and state powers and responsibility get clearly defined through the Union, state and concurrent lists. However, these do not address the issues faced in borderlands of the states where resources are shared on everyday basis. Therefore, what we need is a multidimensional perspective, which helps locate the rights of residents/citizens in a broader discourse of access, unhindered by state boundaries. Just like non-resident Indian origin people can claim benefits in India through OCI status, similarly residents of different states who are placed in the borderlands should be able to have access to opportunities to work, healthcare and education in the borderlands that they live in, without the borders becoming a hindrance. The pandemic has necessitated thinking about daily circulations in state borderlands and how these need to be facilitated within the federal structure of the Indian Union.

This article first appeared in the print edition on July 10, 2020 under the title ‘The regimes of boundaries’. The writer teaches history at Ambedkar University, Delhi.