There is an open question about how much economic loss a nation should take in order to slowdown the pandemic. (Illustration by C R Sasikumar)

There is an open question about how much economic loss a nation should take in order to slowdown the pandemic. (Illustration by C R Sasikumar)

India’s COVID-19 numbers are surging. In terms of the total number of infections, the country has rapidly risen through the ranks to now occupy the third place in the world, behind the US and Brazil, having overtaken Russia over the weekend.

If instead of counting COVID infections, which have a large margin of error, we look at COVID-deaths, and if we correct for population size (as indeed we should), all countries in Africa and Asia, including India and China, come out much better. But within this region, India’s performance is notably bad. In terms of COVID deaths per million population, that is, the Crude Mortality Rate, India is doing worse than China, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bangladesh, Malaysia and many other nations, including most of Africa.

How did this happen when India was one of the first emerging economies to announce the lockdown? The total lockdown did make many observers worry about the economy. It was felt that, since COVID mortality seems to be much lower in Africa and Asia (maybe because of our younger population or some innate immunity), we should not mimic and try to outdo rich European and North American nations in terms of the severity of the lockdown. There clearly had to be a lockdown, but it should have been carefully targeted and curated for our region.

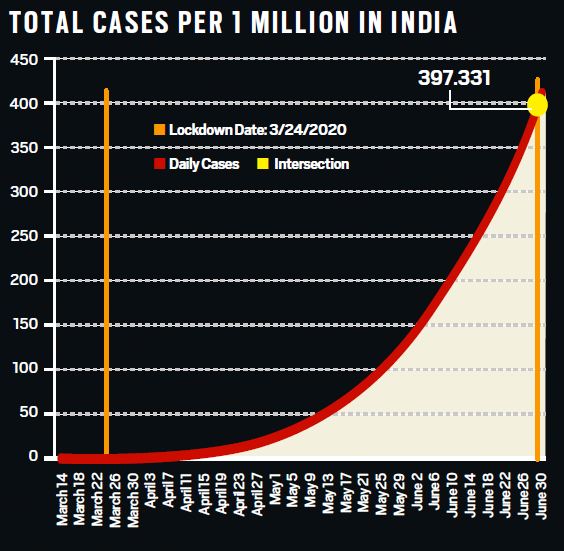

There is an open question about how much economic loss a nation should take in order to slow down the pandemic. In some early writings, I had raised these matters and at the same time appreciated the early action of our government. What happened subsequently turned out to be a double shock. India’s economy is spiralling down and the pandemic is spiralling up. The accompanying graph sums up the story. I am very disappointed about what is happening. The lockdown, announced on March 24, far from controlling the spread of the pandemic, seems to have made it worse. Two weeks after the start of the lockdown, the infection rate picked up and it has been on an alarming upward climb since then.

Why did this happen? India’s lockdown has been described widely as the most stringent in the world. At the time of the announcement, with a four-hour notice, there was a natural expectation that the government had plans of how to handle the sudden stoppage of work and movement of people, and the break in supply chains. But there was no evidence of any of these ancillary actions. I do not have enough information to know what plans there were, but the total absence of any supporting action, to ramp up testing, expand the medical sector and to help the millions of stranded poor workers, was baffling. It was almost as though some people in government — bureaucrats and even some politicians who are part of this government — had decided to sabotage the Prime Minister’s lockdown by sitting back and doing nothing. We know that in the case of South Africa, which also went for a severe lockdown, immediately after the announcement, there was a massive step up in building hospital facilities and testing centres. One did not see that happen in India. In most countries, after the lockdown announcement, minimal transportation was kept open, letting people go home. In India, for weeks there was no sign of any effort to handle the problem of migrant workers, huddled and hungry, far away from home.

Opinion | Society needs to regain moral compass

I am assuming that for such a major announcement with a four-hour notice, there must have been a team of senior bureaucrats who knew and planned this policy in advance. And I know how talented India’s bureaucracy is. Surely, they should have acted to execute the plan. The stories that appeared in the news all over the world, of tens of millions of poor Indians trying to walk hundreds of miles to get home, were tragic. In addition, it damaged India’s global image; India got far worse international press than it may have received any time since independence. The Economist magazine (June 13) estimated that India issued “well over 4,000 different rules” during the first two months of the lockdown, many of those rules being corrections of many of those rules.

Quite how this policy disaster happened will take time to uncover. But one thing has now become clear. The way in which the lockdown was executed, the lockdown itself became the source of the virus’s spread. By having people huddle together, infecting one another, and then having the same people travel hundreds of miles, the pandemic has been made much worse than it need have been.

This double shock is showing up on all data. India’s growth, which had already been on a steady downward trajectory for two years before the pandemic, has now dropped even lower. The IMF has predicted India will end up with a growth rate of -4.5 per cent in 2020, which will be the lowest growth India has seen since 1979. There was an expectation that capital would move out of China because of the pandemic, and India would be a beneficiary. But that has not happened. The big beneficiary seems to be Vietnam and a few other nations, and, ironically, China seems to be holding back a lot of its foreign investment. The unemployment rate in India in May climbed to an astonishing 23.5 per cent, compared to Brazil’s 12.6 per cent, the US’s 13.3 per cent and China’s 6 per cent. China’s official data on unemployment needs to be taken with caution, I hasten to add. But that does not detract from India’s disproportionate poor economic performance and the fact that this price was paid for no purpose.

This article first appeared in the print edition on July 8, 2020 under the title “The virus and the lockdown”. The writer is C Marks Professor at Cornell University and former Chief Economist and Senior Vice President, World Bank