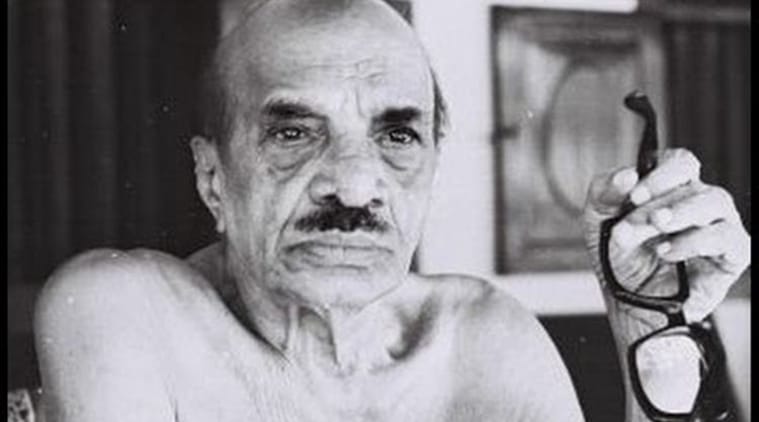

Malayalam writer Vaikom Mohammed Basheer. (Credit: iemalayalam.com)

Malayalam writer Vaikom Mohammed Basheer. (Credit: iemalayalam.com)

Once upon a time in India, before Indian philosophers became institutionalised renouncers, philosophy flourished. But after the first century CE, strangely, the Subcontinent did not produce a single original philosopher. The many philosophical schools that developed here between the second and the 11th century CE, albeit clever and competent, were only interpretations/reinterpretations of thoughts that had originated earlier.

However, 20th century India produced two outstanding original philosophers. One was Gandhi, the philosopher of ahimsa/satya, who invented a new way of life, which finds practitioners even in the 21st century. The other was Vaikom Mohammed Basheer, the well-known Malayalam writer, whose death anniversary fell on last Sunday.

Basheer is not as well-known as Mahatma Gandhi — he cannot be credited with inventing a new way of life that can be called the “Basheerean Way of Life”. This was, I think, largely due to his commitment to Islam — as a committed Muslim, he could never have conceived a way of life, distinct from Islam.

No one has so far proclaimed Basheer as a philosopher; but he was, in fact, a philosopher of goodness. (Illustration: Vishnu Ram)

No one has so far proclaimed Basheer as a philosopher; but he was, in fact, a philosopher of goodness. (Illustration: Vishnu Ram)

Basheer never distanced himself from Islam. But like Gandhi, he tried his best to transform the religion of his birth into an ethical religion through his writings and his style of living. But his reach of influence was confined to his circle of friends and the people who read his writings. Basheer, like his hero Gandhi, was not a “religious” person in the conventional sense. Basheer took the Koranic injunction, “Let there be no compulsion in religion: Truth stands out clear from Error; whoever rejects evil and believes in Allah hath grasped the most trustworthy hand-hold, that never breaks. And Allah heareth and knoweth all things”, literally, and so assumed certain liberty.

To Basheer, the first three pillars of Islam were the most significant ones. The acknowledgment of the first pillar, “There is no god but God, and Muhammad is the Messenger of God”, is visible in all his autobiographical writings. The second pillar of five mandatory prayers, gets a new interpretation in his writings. According to him, helping all the life forms created by Allah is a form of prayer and he practiced this instead of the traditional namaz (prayer facing Mecca five times a day). The third pillar is that of zakat (almsgiving). For Basheer, that was also part of his concept of goodness and so he followed this tradition without fail. He did not see the last two, “fasting” and “pilgrimage to Mecca”, as important enough.

Basheer is not as well-known as Mahatma Gandhi — he cannot be credited with inventing a new way of life that can be called the “Basheerean Way of Life”. (Illustration: Vishnu Ram)

Basheer is not as well-known as Mahatma Gandhi — he cannot be credited with inventing a new way of life that can be called the “Basheerean Way of Life”. (Illustration: Vishnu Ram)

Irony is the most visible trope in Basheer’s writings. Basheer wrote Ana al-Haqq in the mid-1940s. It is a beautiful biographical prose poem about the famous Sufi mystic, Hussein Ibn Mansur al- Hallaj, who lived in Baghdad around the beginning of the 10th century. Mansur al-Hallaj was persecuted and killed because of his heretical pronouncement, “Ana al-Haqq” (I am the Truth).

Ana al-Haqq was republished in 1984 with a short footnote which read: “This story was written some 40 years back. Now I believe that ordinary human beings who are just the products of the All Mighty saying things like ‘I am God’ is a sin. I had also claimed that the work is based on a real story, but now, take it just as a fantasy. Ana al-Haqq”. Many who saw in this a return of Basheer to orthodox Islam, had obviously missed his tongue in cheek repetition of the title of his story — “Ana al-Haqq” — at the end of the footnote.

Since Basheer was deeply spiritual and a philosopher of goodness, it is necessary to talk about a “thinma (evil)” that had gripped him. At one point in his 82-year-long life, Basheer was affected by what he described as “thinma”. His “thinma” was the self-created habit of consuming alcohol. There are many functional alcoholics, but in the case of Basheer, alcohol played havoc and twice he had to be treated for insanity caused by excessive alcohol consumption. But in 1970, I am told, he became a teetotaller. I believe what rescued him from this “thinma” was his spirituality and his innate goodness. He, I believe, was an iconic example of the Socratic dictum, “a virtuous person cannot be harmed”. Socrates himself drank alcohol, but it did not harm (psychologically) or morally corrupt him. That was also true of Basheer. All those who knew him referred to him with utmost respect. His biographer, the scholar-professor, M K Sanoo, called him “the recluse of solitude”, while acknowledging the “thinma” that gripped him at one point of his life. Sukumar Azhikode, the Malayali public intellectual who was also a Gandhian and an anti-alcohol crusader, always compared Basheer with the Upanishadic seers of India and mystic Sufis.

It is only very recently that professional philosophers have come to acknowledge Gandhi as a philosopher. No one has so far proclaimed Basheer as a philosopher; but he was, in fact, a philosopher of goodness. He once defined “goodness” as the act of “giving a little water to a welted plant or giving food to a hungry being”. It is these simple acts of goodness that he practiced and propagated through his writings. Why should we practice goodness? Most of his writings are attempts at answering that question. It promotes “spirituality” in the doers.

What then is “spirituality”? Basheer, unfortunately, did not give a simple definition like he did in the case of “goodness”, but we can glean it from his writings and also from the way he lived.

What does it mean to practice goodness? His 1947 novella, Voices, stands out for its startling novelty. There are only two voices. The voices of an unnamed stranger and the intermitted occasional voices of, again, an unnamed literary personality, who is taking down the “confessions” of the stranger. Most readers of Voices seem to have heard the voices only of the stranger and many, even though they appreciated its craft, they found the autobiographical voices of the stranger too blatantly sexual for their moral sensibilities. In fact, the “stranger” is a paradigm case of “pre-occupation with oneself”. Basheer, in fact, was presenting, through the voices of the “stranger”, the existential crisis such a preoccupation creates. There is no redemption if one is preoccupied with oneself. All that is undesirable emerge from such preoccupation. That is the lesson we get if we pay attention to the second set of voices.

Voices is the story of a stranger, who looks more like an insane beggar and barges into the house of a well-known writer late at night, and pleads with him to listen to the story he wants to tell. The writer receives the stranger with exemplary kindness and promises to listen to what the stranger wants to tell him, the next morning. That is the first manifestation of goodness. Then the writer gets the stranger to bathe and change his clothes. He shares his food with the stranger. The stranger after a sound sleep narrates next morning a harrowing tale of his life. The novella ends with the stranger recounting his failed suicide attempt. Just before that climax, the writer asks: “Have you ever done anything all by yourself and derived happiness from it? Growing things… planting at least one seedling and seeing it bloom and bring forth fruit. Given water to a thirsty dog or food to a hungry person? At least some things like these?

(The stranger replies): “No. I killed people. And I have attempted to commit suicide”

What Voices manifests is the “spiritual” aspect of Basheer’s writings. In most of his writings, there is an implicit theme of the need to guide a disturbed being to a peaceful state, whether that being is a human or a nonhuman form of life. I call this Basheer’s spirituality. That, indeed, is one form of goodness. The writer in the Voices is the personification of that spirituality. Basheer’s contention is that as far as human life is concerned, without disengaging from selfishness, one would not achieve a stable state of peacefulness. The only way one could achieve it is by practising goodness continuously throughout one’s life. Here was a world of innumerable life-forms that Allah had created for humans to practice goodness and to experience perpetual peace. But unfortunately, according to Basheer, the humans instead, convert the whole world into an enormous “blade company”.

Let me end this with an incident that was recounted to me by M N Karassery, a younger writer who was close to Basheer. In the last 15-20 years of his life, Basheer used to walk barefoot. Once when a friend asked him why he was not wearing footwear, his reply was: “I don’t use footwear. It makes me uneasy if I step on this earth with footwear.” This response gives an insight into the philosopher that Basheer was. It was not only humans, but all that he believed to be Allah’s creations, Basheer treated with the same reverence. All creations are Bhoomiyude Avakashikal, that is all beings have equal claim to this earth.

The writer taught philosophy at St Stephen’s College, Delhi University