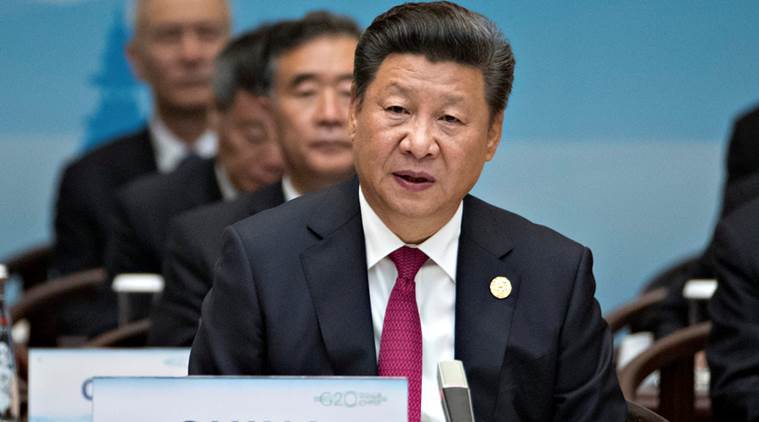

Chinese President Xi Jinping. (File Photo)

Chinese President Xi Jinping. (File Photo)

I am no China expert. And I certainly cannot add to the wisdom already expressed in these pages on the current Sino-India border crisis. But I have had, in a very narrow sense, a ringside view of this conundrum. It has been a staple of our family’s dinner table conversations for decades. So driven by the reflection that the past can offer some, albeit imperfect, guideposts for the future and “one should read nothing but biography for that is history without theory”, I would like to share a few personal vignettes.

My father, Jagat Singh Mehta was a diplomat and to the extent, our foreign service acknowledges specialisation, he was considered a Sinologist. Directly or indirectly, he was engaged with China for most of his working life.

Directly, he was part of the Indian delegation in 1960 that sat across the table from their Chinese counterparts for six continuous months to gather and compile historical data in support of the border claims of the respective governments. The Indian report, which ran into 600 pages, was presented to Parliament in 1961. Clearly these discussions did not have the impact everyone had hoped for as the two countries went to war in October 1962. Almost immediately thereafter, in 1963, my father was posted to the Indian mission in Peking. I remember we lived in a large ugly block of a house. There must have been at least 25 rooms in the house, but we were advised to limit our family conversation to only three rooms. The rest of the house was reportedly bugged. We had eight Chinese “domestics” — they were all spies and made no pretence of being anything but that. Our movement was restricted and we were followed everywhere. It was exciting for us “kids” to live amongst spooks and in the knowledge that perhaps much of what we said was being recorded by someone in the recesses of the Chinese government.

But I suspect my father was on the edge. He was forever returning from banquets to a meal of dal and chawal. This was because the Chinese hosts had a habit of delivering anti-India speeches before dinner. He had to walk out in protest leaving untouched a 20-plus course banquet. I remember one time he came back to claim he might have just acquired the distinction of being the first diplomat to walk out of a banquet hosted by Chairman Mao.

One day, he was summoned to the Chinese foreign office in the middle of the night to receive an ultimatum that India must withdraw a few yaks and demolish some bunkers on the border. Or else… It was 1965 and the India-Pakistan conflict was in full flow. My father advised Delhi not to react. He felt the threat to open a second front was a bluff and no more than an affirmation of diplomatic support for Pakistan. He called it right and was commended for his judgement by Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri. The message of commendation is hung on a wall in our home in Udaipur.

On another occasion, my father, who was back in Delhi, received a call to be told the Chinese had dispatched a plane to pick up two of their diplomats who had been expelled by our government in response to the treatment meted out to our officials a few days earlier. The Cultural Revolution was at its height and the Chinese had accused two of our diplomats of spying. They had put these diplomats on a hopping flight from Peking to Hong Kong and at every stop, crowds at the airports had subjected them to verbal abuse and at times, physical humiliation. My father must have already cleared his lines for I recollect him informing the caller, in no uncertain terms, that were the Chinese plane to breach Indian air space, it would be shot down. The Chinese diverted the plane to Kathmandu.

My father regarded Mao’s China as a disruptive force. He believed Mao was bent on fanning the ideological polarities of the Cold War to get the developing continents of Latin America, Africa and Asia (“the villages of the world”) to “surround” the developed continents of Europe and North America (“the cities”). Mao supported the “Che Guevara” strategy in Latin America, anti-colonial revolutions in Africa, the Naxalites and OPEC’s embargo of oil supplies, all towards this end. He was not interested in any form of detente.

My father saw Deng Xiaoping’s China in a different light. Deng too was motivated by great power aspirations but sought to realise them through policies that blended with the rules-based framework of the post-World War II multilateral system. My father believed that the Sino-India border issues could have been legally resolved during the Deng era. That they were not was because of the exigencies of our domestic politics.

I suspect my father would have regarded President Xi Jinping’s China as cut from the Maoist mould. He would have argued that President Xi’s aggressive and expansionist “Belt and Road” strategy bore comparison with Mao’s policy to polarise the world between the “haves” and “have-nots”. That China’s heavy-handed moves to change the status quo in the South China sea, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and now the LAC, are contemporarised mirror reflections of Mao’s efforts to upend the established international order.

One can only speculate as to why President Xi decided to trigger the crisis with India. But if he does indeed think like Mao, he may have made the strategic calculation that, given the weakened state of the Indian economy, a conflict with India would be a low risk way of distracting attention from his domestic vulnerabilities.

I know my father would have advocated India find a diplomatic solution to the current imbroglio. No one gains from conflict. But given his experience of Maoist China, he would have also urged that our velvet glove of diplomacy must now cover an iron fist of resolve.

The writer is Chairman and Senior Fellow, Brookings India