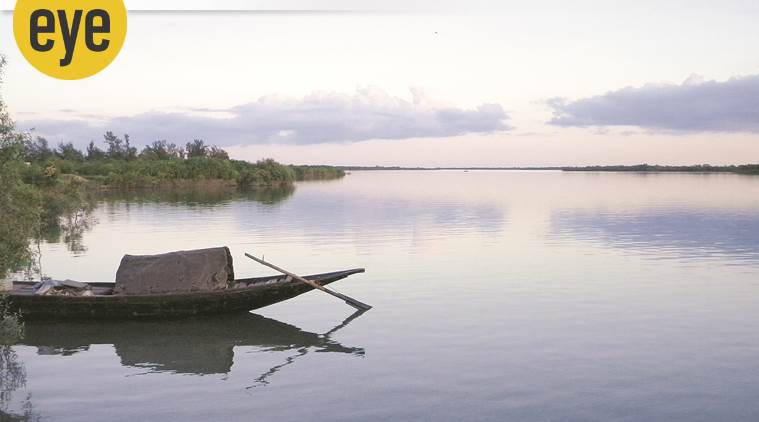

People of the Sundarbans live in close proximity to tigers, crocodiles, snakes and sharks. (Mousumi Mandal/Picture courtesy: Sahapedia)

People of the Sundarbans live in close proximity to tigers, crocodiles, snakes and sharks. (Mousumi Mandal/Picture courtesy: Sahapedia)

How does a goddess defeat a storm? When Amphan swept through the Sundarbans on May 20, theatre actor Anita Mondal, who lives in Annpur, a remote village on the islands, crawled under a charpai with her husband and children. “Even if the walls fell, we would live if we hid under the bed,” she says over the phone, a month later. Clutching a bag of precious belongings, she heard the wind tear down huge siris trees and coconut palms, and blow away the thatched roof of their house. As the ground began to tremble, they grabbed the legs of the charpai to keep it from flying away.

As the storm raged, Mondal was praying for help from the protagonist she plays on stage on calmer days — Bon Bibi, the deity of the forest and the central character of Bon Bibi’r Palagaan, a musical drama unique to the Sundarbans. “We do not have a roof but I feel blessed. Bon Bibi saved our lives,” she says.

The Sundarbans boasts of almost 30 troupes that perform Bon Bibi’r Palagaan in various islands through the year. Traditionally, the performances are held near Bon Bibi temples or villages bordering the forests, in the light of solar lamps and bulbs powered by generators. Mondal has essayed the role of the goddess for 20 years now, which means something in the Sundarbans, where the audience comprise people who go into the mangroves to collect honey, prawns, fish or crabs every day. They see the play as a part of their daily life, for it is by the grace of Bon Bibi that they believe they survive in tiger country.

Like everything else in the Sundarbans, Amphan has ravaged through the art form and its practitioners. The pink sari that Mondal’s Bon Bibi used to wear on stage has been wrapped in a plastic packet and put away. The spaces where the palagaan used to be played are now sites of destruction. The island has not had a single performance for more than three months, the longest in recent memory. Its poetry lies submerged in brackish water. “I have no work so I am sitting at home. The only time I go out is to get traan (relief),” says Uttam Barik, a rickshaw-puller from Gosaba, one of the main islands of the Sundarbans, and a third-generation performer.

In the largest continuous mangrove forest in the world, humans reside a short distance from a thriving population of crocodiles, snakes, sharks and man-eating Royal Bengal Tigers. Many of them depend on the forest for their livelihood as fishermen, crab-collectors and gatherers of the thick and strong honey that grows in combs on the hetal, gorjon, goran and sundari mangrove trees.

The people of Sundarbans believe that you can enter the forest anytime you like. Whether you will leave it depends on Bon Bibi. Last month, alone, one man went out to get firewood from the forest and another to fish. Tigers took them both. Hence, the 54 inhabited islands of the 102 deltaic islands of the Sundarbans are studded with temples to Bon Bibi and her twin brother, Shah Jongoli.

Legend has it that Bon Bibi was born far away in Saudi Arabia. Her father was Fakir Ibrahim, who lived in Medina, and her mother was Gulal, a woman from Mecca. “Bon Bibi realises that they have been sent to earth to fulfil a divine purpose and must leave Medina and that is how she reached the Sundarbans,” says Kanailal Sarkar, 66, author of History of Sundarbans (2011), who was born in Lahripur, a village in Gosaba.

The palagaan recounts her birth and the story of Bon Bibi and Shah Jongoli’s triumph over the fierce Dokkhin Rai and his mother Narayani, who represent tigers. It is the third part of the story, Dukhey Jatra, which is most performed in the Sundarbans. “In the play, we are a group of honey-gatherers who go to the forest with a little boy called Dukhey. His mother wants him to stay home but cannot afford to feed him as they are desperately poor. When you have nothing to eat, you have no choice but to go to the forest to work, just like us. Unfortunately, Dukhey does not return from the forest. The honey-gatherers tell his mother that he has been taken by a tiger and will never return to her lap again,” says Barik. In the forest, the child calls out to the goddess for protection. Bon Bibi rescues Dukhey and restores him to his mother.

“When I visited the Sundarbans in 2014 for research, I stayed in several remote villages of Gosaba. Something fundamental about the people, especially those who were very poor, was that they identified themselves with Dukhey and thought of themselves as Bon Bibi’s children,” says Amrita Sen, assistant professor in the department of humanities and social sciences at the Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur.

In one of the most ecologically fragile regions of the world, a strict code, tied to the belief in Bon Bibi, governs human acquisition. The islanders believe that one must enter her kingdom without carrying any weapons. “…the islanders often explained that Bonbibi (sic) had left them the injunctions that they were to enter the forest only with a pure heart/mind’ (pobitro mon) and ‘empty hands’ (khali haathe). The islanders explained that they had to identify completely with Dukhe, whose unfailing belief in Bonbibi had saved him,” writes anthropologist Annu Jalais in Forest of Tigers: People, Politics and Environment in the Sundarbans (2010).

The farthest shores: A performance of the ‘Bon Bibi’r Palagaan’. (Poulomi Das/Picture Courtesy: Sahapedia)

The farthest shores: A performance of the ‘Bon Bibi’r Palagaan’. (Poulomi Das/Picture Courtesy: Sahapedia)

“You must also not take more than you need,” adds Sen. You may enter only if you have nothing to eat at home and have to seek your livelihood in the forest. You must not defecate in the forest, smoke beedi or wash utensils. “I never carried any weapons when I went into the forest to fish or catch crabs. Bon Bibi would be angry if I did. She is the one who protects me in the forest,” says Sanjit Mondol from Pakhiralay, a village on Gosaba island. What if he were attacked? “When a tiger chooses you, there is nothing to do anyway,” he says.

Sanjit is a regular member of the audience of Bon Bibi’r Palagaan, whose story can be found in a 19th-century text called Bon Bibi Johuranama (The Chronicles of Bon Bibi’s Glory). “It is difficult to confirm whether the performative text of the palagaan precedes the printed johuranamas or vice versa,” writes Mousumi Mandal, assistant professor, Presidency University, in Bonbibi-r Palagaan: Tradition, History and Performance, on Sahapedia. The language of the johuranama is Musalmani Bangla, written in the Bengali script, but with the book opening to the right, in the Arabic style. “Her worshippers do not think of her in terms of ‘Muslim’ or ‘Hindu’ but as a ‘forest super-power’ who extends her protection over individuals of all communities equally,” writes Jalais. “When people read Bon Bibi johuranama, they punctuate the verses with a chorus of ‘Allah Allah Bol (Say the name of Allah)’,” adds Mehebub Sahana, a research associate in the School of Environment, Education and Development, University of Manchester, the UK.

There are no documents to confirm when the performances started, a problem with most folk art forms in India. Sahana says that the Bon Bibi cult spread during and after the Great Bengal Famine of the early 1770s, which killed lakhs. “Since agriculture was destroyed by the famine, people who lived and farmed in the upper parts of the Sundarbans, came to the lower parts of the islands to fish and live off the forest. They became bonojeevi or people who work in the forest. As the pressure of humanity grew on the forests, there was the inevitable clash with wild animals, especially tigers,” he adds.

In the palagaan, human protagonists are not the heroes but the subjects or prey of nature — a lesson that the pandemic is spreading across the world. People reduced to their primal condition — frail skin and bones, fear and helplessness — against the whims of nature is the old normal. And so, the actors of Bon Bibi’r Palagaan not only educate or entertain but also advocate total surrender. “When we go into the forest, we think, ‘Ja hobey hobey, sheta porey bhaba jaabey. Jodi phiri toh bhalo, na phiri toh ki kora jabey?’ (Whatever has to happen will happen. If I return home, it would be good. If I don’t, nothing can be done about it),’” says Sanjit.

In a scene in the play, the fishermen are in the middle of the huge Raimongol river, which is so vast that you cannot see its end, when clouds sweep through the sky. They do not ask the waves to recede. They submit, asking the boatman, to row the boat quickly and take them ashore, with the help of Bon Bibi.“When you see a wild animal, you should not fight but move out of its way. If a tiger has chosen you, only Ma Bon Bibi can save you,” says Anuja Adhikari, 37, from Lahripur village in Gosaba, who also plays the deity in the Bon Bibi’r Palagaan. She runs a kirana shop and catches fish and crabs in the forest. “The money I bring home runs the family. The only time I forget my troubles and feel happy is when I act and sing as Bon Bibi. I have faith that Bon Bibi will look after us,” she says.

A few years ago, when she was returning home after playing Dukhey’s mother in Bon Bibi’r Palagaan, Adhikari smelt the animal nearby. “The tiger had crossed the river from the forest into the village. I kept telling myself, ‘Ma achche, oshubida hobey na’ (Mother will look after me),” she says. She found the tiger in a cattle shed of a milkman. “If the tiger had not found its aahar (food) in a cow that day, I wouldn’t be alive. Through my performances, all I want to tell people is to have faith that Bon Bibi will save you,” she says.

Battered by cyclones through the ages, and now buffeted by the pandemic as well as Amphan, the Sundarbans is down to its last dreg of resilience. Life on the islands will only become harsher with the rise in sea temperatures and climate change. In this turmoil, the palagaan will also have to adapt, as it has in the past. While night-long ritual performances were still held, tourist lodges had become the new platform in the last few years, with shows tailored to suit foreigners or metropolitan Indians looking to experience an exotic Indian art.

But, increasingly, it is becoming hard to keep the faith. A few years ago, Sanjit used to play Dukhey in Bonbibi’r Palagaan. The family had a fishing boat at the time that cost Rs 15,000. During cyclone Aila in 2009, the boat was tied tightly to a tree by the side of the river. “When we went back after the storm, it was in splinters. Machine parts had been flung on the bank. Aila also destroyed our house, broke the river’s dam and flooded the island,” says Sanjit. He decided to end his career on stage. “I could also see that the days of Bon Bibi’r Palagaan were numbered. A lot of people are not accepting of the Bon Bibi faith anymore,” he says. Today, the 23-year-old is a construction worker in Tamil Nadu and other parts of West Bengal and an eco-tourism guide in the Sundarbans.

On the other hand, the island has sent out its first graduate from the National School of Drama in Delhi. Sajal Mondol, 38, who graduated in 2011, chose to return home to work in the local theatre form. He staged a major show of the palagaan in 2013 in the Sundarbans and Kolkata and was supported by the state’s ministry of culture. But he, too, discovered that the Sundarbans did not offer opportunities to an artiste.

Across the world, theatres are shutting down as a virus stipulates new rules of social interaction. Will the palagaan be staged again? Adhikari says, “Things will be all right, have faith in Bon Bibi. The pandemic will be over soon and we will, once again, sit together to pray and perform. After all, Sundarbans will not be Sundarbans without Bon Bibi.”