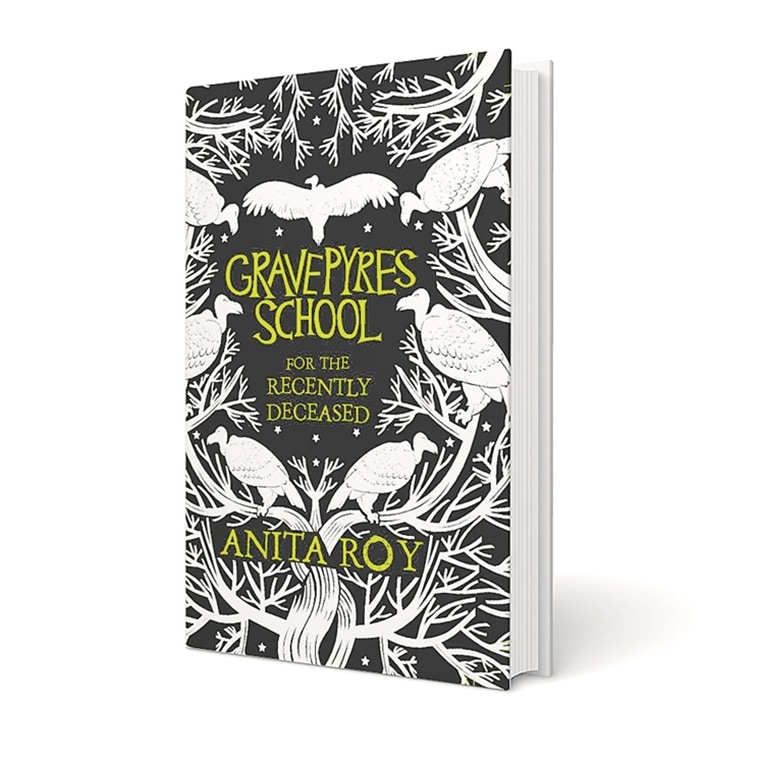

Till death do us part: Gravepyres School for the Recently Deceased is Anita Roy’s first novel, meant for young adults.

Till death do us part: Gravepyres School for the Recently Deceased is Anita Roy’s first novel, meant for young adults.

Editor-writer Anita Roy, 55, has played a pivotal role in Indian publishing for children and young adults. In 2004, she set up Young Zubaan, an imprint that promotes diversity in children’s publishing; she was also one of the founding members of the popular Bookaroo Festival of Children’s Literature in 2008. In this interview, the UK-based Roy speaks about her debut YA novel on death and ecological destruction and darkness in children’s literature. Excerpts:

Gravepyres School for the Recently Deceased is out at a time when the world is facing its own fragility. What made you contemplate a book on death?

There’s a point in the novel when Jose, the main protagonist, remembers his grandfather saying: it’s amazing how it’s the one thing that is 100 per cent guaranteed to happen to everyone, and, yet, no one ever imagines it will ever happen to them. It is extremely difficult to contemplate the fact of your own mortality. The psychiatrist Irvin Yalom has a phrase for it: ‘staring at the sun’. In his book of the same name, he writes: ‘I feel strongly — as a man who will himself die one day in the not-too-distant future and as a psychiatrist who has spent decades dealing with death anxiety — that confronting death allows us…to re-enter life in a richer, more compassionate manner.’

There’s a great question I was once asked: ‘What is the opposite of death?’ Immediately, the answer comes, ‘Life!’ but that’s wrong. The opposite of death is birth. Life, when you really get down to the truth of the matter, has no opposite.

I wanted to find a way to begin to explore some of these quite difficult, philosophical and spiritual matters in a way that made them accessible to kids. In a way that did not fudge or soft-soap the heartbreaking fact of death’s finality, but ended on the tremendously positive note of interconnectedness.

To be honest, I worried about the book coming out just as the COVID-19 crisis was accelerating all over the world when death is so much ‘in the air’. Would people dealing with real grief, real loss, be offended at the lightness of tone, the humour, the laughter? A good friend of mine died of COVID-19 last month and I can almost hear her cackling at the thought.

Death may be sad — I want a much, much bigger word but it will have to do — but it is serious not solemn, mysterious rather than morbid. The ecological catastrophe that we are currently experiencing stems from the same inability to deal honestly and openly with our own mortality. We have bought into the myth that life — or at least our human lives — can be lived without limit or consequence. A large part of the story of Gravepyres is also about the disastrous consequences of trying to stop the natural flow of time, the natural processes of death, decay and rebirth.

Do you see the pandemic affecting how we approach grief as a community? How differently do you see children reacting to bereavement?

I hope that one of the many things that we learn as a community is how connected we are. I have been astonished by how much compassion has been shown by people — helping others became (for a time at least during the lockdown, here in the UK) a sort of national characteristic.

It has also focused our concern on the most vulnerable — the elderly, those in care homes. How we care for our elderly is how we, too, will be cared for when we reach that point. How we treat the sick is how we, too, will be treated. How we grieve is how we would hope others might grieve for us — for love and grief are minted together to make that precious coin.

How has it affected children?

Well, I don’t know — but I do worry. I worry that it has promoted a sense that a world outside is a place of danger and other people are a source of infection. I worry about building empathy in a world where hugging is seen as transgressive and possibly fatal.

A lot of children’s literature, both contemporary and traditional, have quite dark themes.

Gravepyres School for the Recently Deceased by Anita Roy.

Gravepyres School for the Recently Deceased by Anita Roy.

When do you think the trend arose to present a rosy view of the world to children? And, again, how did we return to keeping things real?

In India, 15-20 years ago, there was a strong sense that there were certain topics that weren’t suitable for children, certain things you could and couldn’t — and shouldn’t — say. The emphasis was on single-issue, morally improving tales, usually involving clumsily drawn anthropomorphic animals. Things have massively improved thanks to a slew of creative and imaginative writers and illustrators coming up through the ranks, whose work has been championed and supported by commissioning editors, mostly women! Children’s publishing in India today is a much broader church, with books that ‘keep it real’ and others that gleefully keep it fantastic! The whole spectrum is necessary.

If I look at the current crop of titles for children (middle-grade as well as a young adult) they seem to be falling over themselves to explore dark themes. Drug addiction, conflict, sexual abuse, racism, sexism – it seems like there aren’t any subjects that are off the table. There are many, many positives to be had from this: not least the empathy-building work that children’s literature is so very good at. The importance of seeing ‘people like me’ in the stories that you read is vital for children to grow up having a healthy sense of who they are and what they might hope to become.

There’s a delightful mix of English, Arabic, Indian, French and Spanish being used in the afterlife in Gravepyres. Do you envision it as more accommodating of our many cultural influences?

I am all for cultural confluence. Maybe, it has partly to do with my own background — half-Bengali, half-English, who grew up in the UK but spent half my adult life in India. With access to films, books, videos and music from every corner of the globe, today’s children are much more open to other cultures than, perhaps, they would have been in the past — and Indian children, in particular, are adept at swimming in different cultural and linguistic streams. And, at the end of the day, we are all united in our shared mortality. We’re all going to die — whether you are Inuit or Sentinelese, from Buckinghamshire or Johannesburg.