Recent years have seen a glut of titles invoke ronin imagery, including last year’s Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice was set in a supernatural 16th century Japan, collected several GOTY awards

Recent years have seen a glut of titles invoke ronin imagery, including last year’s Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice was set in a supernatural 16th century Japan, collected several GOTY awards

It took the briefest of looks at Ghost of Tsushima for the comparisons to begin. Is this the Akira Kurosawa game the world has been waiting for?

The last big release on the PlayStation 4, the open-world game set on the titular island of Tsushima lets the player control Jin Sakai, a samurai out to defend his country against the Mongol invasion. US-based Sucker Punch Productions have painstakingly recreated 13th-century Feudal Japan, consulting Japanese cultural experts on religion, costume, sword-fighting, etc. An audio team was even sent to modern Japan to record ambient sounds.

As the July 17 release date approaches, ‘Best of Kurosawa’ lists are populating websites, posing as unofficial preambles to Ghost of Tsushima. Developers too have consistently name-dropped the legendary Japanese filmmaker, whipping up enthusiasts who have longed for a chance to play out a samurai adventure in the style of Kurosawa.

But what exactly is the Akira Kurosawa style?

Author Eric San Juan spent a year devouring the filmography multiple times before putting together ‘Akira Kurosawa: A Viewer’s Guide’. His drive? A wish to explore Kurosawa’s art beyond the action and charisma of his perennial leading man, Toshiro Mifune.

“From a technical standpoint, he created a lot of the language of modern action movies. When you see the sweeping camera work in Baahubali or the Avengers or in cowboy movies, you’re seeing Kurosawa’s influence,” says San Juan. “Before Kurosawa, action usually looked no different than it would if you were seeing it on a stage. In his movies, the energy explodes off the screen. Every modern action movie owes a debt to him.”

San Juan adds: “His other traits are just as important. Most of his movies involve a lone man struggling against a larger system… Sometimes his stories had bleak endings and his heroes failed in the end. I think Kurosawa would not see this as depressing, because the journey and the struggle are just as important as whether or not you succeed.”

Any action blockbuster this side of the 1950s can trace its lineage back to Kurosawa. Without Yojimbo, there would be no Fistful of Dollars and, one could argue, no spaghetti westerns or Indian masala. There might not have been Star Wars, and the countless derivatives, either. George Lucas used Kurosawa’s narrative structure and visual cues, as well as two point-of-view characters in R2D2 and C3PO as framing devices.

Closer home, the legend goes that S Balachander caught a screening of Rashomon, wrote an inspired play that was rejected by the All India Radio, and turned it into Sivaji Ganesan-starrer Andha Naal. Legacy of the 1954 classic, often considered the first Tamil noir, lives on through Kamal Haasan’s Virumandi to the films of director Vetri Maaran. “If I am getting caught in a mundane situation in terms of writing, unconsciously, I start wondering how Kurosawa would think about it,” Maaran said in an interview.

Odes to Kurosawa in video game form though have been strangely limited, even though the medium now commands more cultural currency than movies and music.

Award-winning actors have migrated to voiceover booths and are donning performance capture scuba suits. The story-telling is increasingly original, and video games have already captured film genres as broad as noir and western, or as specific as heist-capers or Hong Kong crime.

Samurai, too, have long been a staple. And recent years have seen a glut of titles invoke ronin imagery, including last year’s Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice was set in a supernatural 16th century Japan, collected several GOTY awards.

Why, then, is a definitive Akira Kurosawa experience missing from the catalogues? Well, there have been attempts.

To commemorate Seven Samurai’s 50th anniversary, a futuristic adaptation called Seven Samurai 20XX was released in 2004 as an official Kurosawa Production. In its review, Game Informer said the game “offers nothing but mindless button-mashing, boring level design, and horrible pacing.”

You can’t get Kurosawa any more wrong than that.

The same year, production began on a game adaptation of an unfinished Kurosawa script — inspired by the Edo Period (1603-1868) English-born samurai William Adams. Nioh drew praise upon its release in 2017, but 13 years in development hell seemingly sucked all Kurosawa influence out of the game. Developers stopped mentioning his name and barring the blond protagonist and the basic premise, there’s no way of knowing how much of Kurosawa made it to the final game.

Like Kurosawa, there are other filmmakers whose craft transcended regional identities and spoke a universal language. But nobody is clamouring for a quintessential Satyajit Ray or Jean Luc-Godard video game.

It’s because, on paper, an Akira Kurosawa video game should be easy enough to pull off. There’s the structure, the man-against-the-system narrative, the skillfully executed set-pieces. Throw in a stoic swashbuckler and you’re halfway there.

Writer and editor Chris Priestman — whose 2015 article in Kill Screen noted the ‘difficulty of making a videogame that honors Kurosawa’ — says the work “actually lends itself to games more than most”.

“His films — and by extension, samurai cinema too — often have a hero and a villain, violent and epic battles, and the characters usually have an intimate relationship to a location either through exploring it or by fighting for it. Those are elements that games have proven they can do a lot with and that they usually excel at using as mechanics and mission structures,” says Priestman.

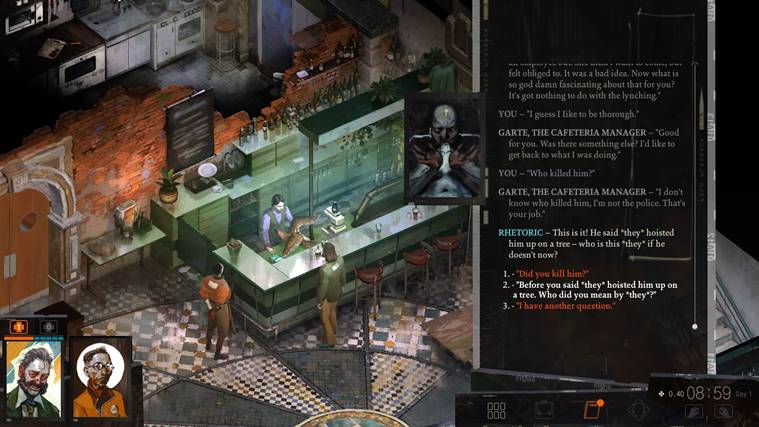

There are games that meet the aforementioned criteria with varying degrees of success. High-profile releases like Horizon Zero Dawn and Red Dead Redemption 2. And indie successes like Disco Elysium — a strikingly-unique role-playing game (RPG) with memorable writing and a thick, brooding atmosphere.

Priestman, who worked on Disco Elysium as a writer and producer, says it’s “specifically the ‘Kurosawa style’ of cinema that is a lot harder to capture in a game.”

“Especially the way he uses environments and visual contradictions in a shot to create emotion and meaning — which you usually have to dig out yourself… it’s not served to you on a plate,” says Priestman, who studied samurai cinema as part of his film studies course.

It’s easy to praise Kurosawa films for the cinematography. Priestman elaborates how the director “brought together the moving parts of his film to a head in a single, beautiful shot — or sequence of shots that he’s constructed as one moment”.

“I often think of his films as being about the struggle of the Japanese peasant class, which gives them an innate nobility — and it’s that which makes it easy to get behind his heroes,” says Priestman. “In his best shots, you can sense the larger political, environmental, and cultural stakes of that historical snapshot.”

San Juan believes the signature use of the camera is what stands as the biggest challenge for a game trying to channel Kurosawa.

“The camera is often one of the most difficult parts of making any video game play well, and in the case of capturing Kurosawa’s style this is one of the biggest hurdles. Video games usually demand player agency, but Kurosawa’s camera was very subjective, moving and probing in order to convey a message, help us better understand a character, or put us further into the action. Except in cutscenes, I don’t know how a developer might accomplish this in a game,” says Juan.

But what if a developer chooses to approach Kurosawa through his own lens?

In 2005, Esteban Fajardo built a video game for his 5th-grade science fair. Ten years later, he was part of a team of students from the University of Southern California who won a BAFTA award for the indie title Chambara.

“Our team did not have any trained animators, and very few artists, but we made a game that was able to convey some of the emotion of a chambara film, even though our resources were very limited,” says Fajardo, who worked as the lead designer on the project.

Named after the Japanese word for Samurai cinema, Chambara was born in the USC dorms as a competition entry and received BAFTA’s Ones to Watch Award, among other recognitions. It is a hyper-stylised multiplayer game that combines stealth and action, allowing up to four players to battle it out in a largely monochromatic arena.

The influences are apparent. Chambara draws from Genndy Tartavosky’s Cartoon Network classic Samurai Jack. Two dozen Zatoichi films, based on the fictional anti-hero, remained in constant rotation during the game development: “It seemed like an appropriate reference; Zatoichi is about a blind ronin, and in Chambara, you cannot see your opponent most of the time!” Fajardo says.

The biggest influence, however, remains Kurosawa. Not only is the hypnotic light and shadow motif in full effect, but the combat pacing was also guided by Yojimbo and Sanjuro.

“In a typical samurai film, the combatants closely watch the body language and stance of their opponent. There is silence and tense contemplation before there is action. We substituted body language with spatial placing — the players can be invisible if they are positioned correctly,” says Fajardo.

The action is methodical, and developers wanted the tension “to build like a balloon expanding, and you don’t know when it will pop”.

via GIPHY

“Some people have remarked that our game feels slower than other FPS (first-person shooter) games, but it is worth it for that split second before you get hit with a sword — when you can see your opponent striking, and all you can do is think, ‘Oh no, I messed up!’,” Fajardo says, adding. “Sanjuro famously ends with a tense stand-off that erupts into a geyser of blood — that was the most important emotion we wanted to capture with our action.”

The iconic blood spray is also distinctly Kurosawan, but Chambara’s target demo skewed slightly younger. The samurai thus were replaced with anthropomorphic bird-ronin, the swords with fish or umbrella, and the gore with a burst of feathers.

“As a creator, I believe the ideal way to live up to Kurosawa is to create games that push new mechanics and carefully consider the symphony of every element of its creation. The nature of games is very different from film, so a game may never make us feel the same way we do when we watch Seven Samurai. Some games can make us wish we were watching a samurai movie, but our goal was to make players wish they were playing Chambara the next time they saw a samurai movie!”

x-x-x

It’s been five years and several samurai video game releases since Priestman first broached the problem the medium faces in adapting the Kurosawa style. And while he stands by his assessment — “it’s still hard to honour Kurosawa’s films through games as it takes a lot of work to be loyal to anything” — Priestman adds that modern technology has made it a lot more variable.

“If you have the right intentions and enough resources then that kind of samurai game is definitely possible,” says Priestman.

Which brings us back to Ghost of Tsushima. By all accounts (and pre-release footage) developers Sucker Punch Studios have done their homework. Combat looks apposite, if not wildly fresh. The uncluttered screen gives way to stunning vistas of winding forests and orchid-laden hills. No arrows or waypoints to guide you on your path. Follow instead the direction of the wind, another narrative device featured prominently in Kurosawa’s cinematography.

“Ghost of Tsushima looks like the samurai game I’ve been waiting for,” says Priestman. “From what I’ve seen so far, I think its use of an open world fits in greatly with how Kurosawa portrayed samurai against a natural backdrop. It looks like it’ll portray the proper breadth of the samurai lifestyle too — slow and fast, spiritual and profane, peaceful and violent.”

Then there’s the gimmicky black-and-white overlay, unofficially dubbed ‘Kurosawa filter’. The overlay can be turned on from the beginning of the game, alongside a Japanese voice track with subtitles. It removes all colour and adds a film grain texture. It also makes the audio sound older and the wind louder.

“I’d argue that Kurosawa’s cinema was more than just black and white — his use of chiaroscuro, staging, and framing for starters — but it’s a great homage to have in a game that should have one, and that offers so much more as tribute to Kurosawa than just a filter named after him,” says Priestman.

San Juan hasn’t closely followed the development of ‘Tsushima’ but can see its appeal to fans. Asked what his perfect Kurosawa game would look like, the aficionado shares compelling mashups.

“It’s easy to imagine Seven Samurai presented like a strategy game akin to X-Com or Shadow Tactics: Blades of the Shogun, where you gather together a squad made up of warriors with varied abilities, map out a plan, and execute that plan,” says San Juan. “Or maybe I could see The Hidden Fortress adapted into a Bioware-inspired RPG, where stealth, subterfuge and smart dialogue choices are just as important as skill with a blade.”

The examples are stellar potential sales pitches, but they also illustrate that there’s no correct way to emulate Akira Kurosawa, as long as a game stays true to his ethos. Like Ghost of Tsushima, artists can try to best recreate a samurai film. Or they can interpret traits and style and fuse them with a novel identity, like Chambala.

“That’s what sets Kurosawa’s samurai films apart from others of the genre, and it’s why a video game adaptation could and should be more than just an action game,” concludes San Juan. “His narratives tend to be about people struggling against forces bigger than they are, and isn’t that what most video games do? They put the player against impossible odds and ask them to rise to the task.”