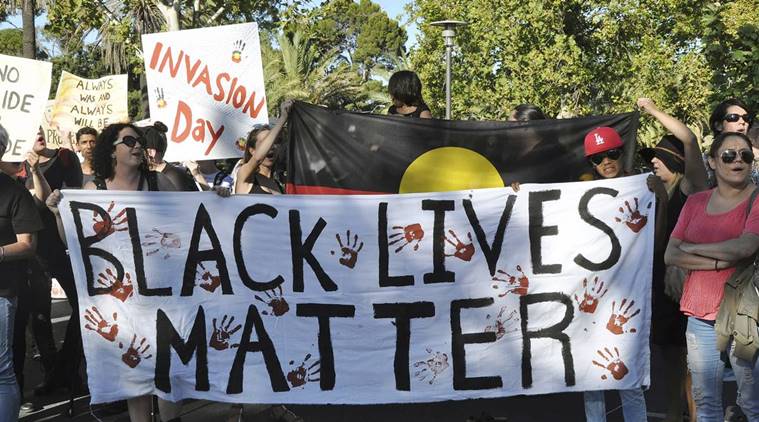

Many people are dismayed that an open season has been declared on statues in the aftermath of the Black Lives Matter protests in the US. (Tim Dornin/AAP Image via AP)

Many people are dismayed that an open season has been declared on statues in the aftermath of the Black Lives Matter protests in the US. (Tim Dornin/AAP Image via AP)

Human beings indulge in many valuable forms of meaning-making, but the urge to create statues of famous people (typically long dead), and place them in full public view, is not one of them.

Aesthetic gratification is certainly not the reason such statues exist. Sure, Michelangelo used his chisel to create some pretty dishy stone avatars, but his works are the exceptions that prove the rule. The use of public space to put up statues of human beings, living or dead, is a deeply political act. Decisions to implement these legacy projects, placing (literally) on a pedestal the likeness of an individual in public, are not made without serious consideration of cost, benefit, and impact on various social groups

Statues exist at the very least to enable cults of personality (Winston Churchill, Mahatma Gandhi, Che Guevara, Shivaji). More often than not they are used to make statements of power (Stalin, Mao, and most recently in the news during the Black Lives Matter protests, Robert E Lee — commander of the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War). Like all propaganda, statues exist to create an idealised, heroic, worshipful image of a public figure. There are no shades of grey in a statue. No room for human frailties and flaws.

A recent article in the Indian Express, ‘The statue toppling spree’ (IE, June 30) argued that it is pointless to fight the past and that the toppling of statues only serves to shut down the debate about our shared history. On the contrary, it could be argued that the act of pulling down statues is a very useful and necessary way of challenging the historical records invariably shaped by the biases of those who did the recording, and negotiating change in the present.

Seen as a form of propaganda, statues are an effective way of establishing the sacred cows that dare-not-be-challenged in any society. Only when the tide of popular sentiment rises and gathers sufficient courage to question the supremacy of the ideas that statues represent, is there an opportunity for progress and change.

Many people are dismayed that an open season has been declared on statues in the aftermath of the Black Lives Matter protests in the US. In the UK, statues of Winston Churchill, Christopher Columbus, Edward Colston, Cecil Rhodes, King Leopold of Belgium and even Mahatma Gandhi have all been targeted by the ongoing Topple the Racists campaign. It appears no one is beyond reproach. But perhaps this is as it should be. Perhaps we ought to consider that it is healthy for human societies, if statues come with expiry dates. That it is the fate of all statues to one day be interrogated, and if need be pulled down as societies evolve and as new ideas and sensibilities take root.

Statues are an important, publicly visible aspect of the brainwashing seen to be necessary for the creation of a unified sense of nationhood and shared values. In their respective countries, students are indoctrinated into hagiographical, heroic narratives around Gandhi, Jinnah, Churchill or Washington. Their ubiquity — from currency notes to statues — is designed to prevent a wholesome understanding of the thorny complicated lives they led (no different from human beings elsewhere).

We fall for political propaganda that chooses to remember a limited set of icons, and refuses to allow any challenge to the sanctity of their memory. By refusing to judge these icons by today’s standards we choose to wear blinders that are untenable in our complex, globalised, modern world where one man’s hero is invariably another’s villain. Barack Obama – a global icon who will no doubt be memorialised through statues in years to come – is also responsible for the deaths of thousands of civilians through bombs and drone strikes that he authorised across the Middle East, Pakistan, and Afghanistan.

Given, however, that the political imperative for statues is unlikely to ever go away, statue-building as a counter to statue-toppling is also a necessity. The statues in Lucknow’s Ambedkar Memorial Park serve to correct the unjust erasure of Dalits from public spaces in India, and commemorate their long and ongoing struggle for social justice.

Equally, there are times when the state-sponsored toppling of statues can be deeply regressive. The Taliban might have destroyed the Buddhas of Bamiyan but so powerful and deeply entrenched are the ideas of the Buddha that no toppling of statues can dilute them. Powerful ideas simply mutate and proliferate. Buddhist thought has given meaning to contexts as varied as pop culture, the wellness industry and Dalit socio-political identity.

The young poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792 – 1822) saw most clearly, that in the end, most statues are nothing but the human ego writ large, doomed to end up as rubble, proof of mankind’s infinite hubris. The dramatic visual that Shelley gifted us – the statue of an arrogant, sneering Ozymandias, king of kings, lying shattered in the desert sands – endures as a beacon of hope, reminding us of the ephemeral nature of political power in today’s troubled world.

The writer is a consumer researcher and part of the founding team at Junoon Theatre