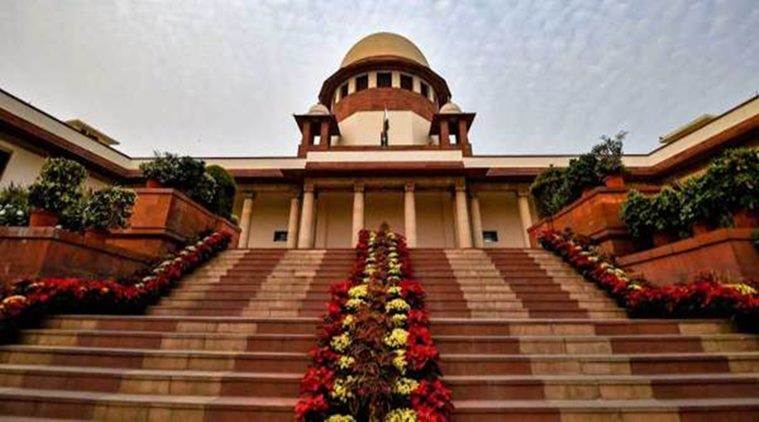

Now that the Court is proactively adopting technology, it must expand the right of access to justice by live-streaming proceedings. (File Photo)

Now that the Court is proactively adopting technology, it must expand the right of access to justice by live-streaming proceedings. (File Photo)

The pandemic has presented the Supreme Court with both a challenge and an opportunity to adopt technology. As the lockdown began, the Court had to quickly find the technology and create protocols for virtual courts and e-hearings. Before this, the judicial system assumed that litigants, judges, lawyers, and court staff could come together in a physical place for the administration of justice. There was an open courtroom that the public could access. This protected the right to access justice, guaranteed under Article 21 of the Constitution. COVID-19 presents the judicial system with an opportunity to find ways to ensure access to justice even without a physical courtroom.

Now that the Court is proactively adopting technology, it must expand the right of access to justice by live-streaming proceedings. Further, court proceedings must also be documented and preserved for posterity. Both audio-visual recordings and transcripts of oral arguments should be maintained for this purpose.

While the Indian Supreme Court has enjoyed a reputation as one of the world’s most powerful and influential courts for several decades, regularly deliberating on matters that changed the course of public life, yet the Court maintained no public record of its own proceedings. Nor were its proceedings broadcast live for public viewing. Over time, security concerns meant that the public could only enter courtrooms in the SC with a pass. Due to space constraints, law students were not permitted to enter court rooms on Mondays and Fridays when the Court heard fresh matters.

In its 2018 judgment in Swapnil Tripathi v Supreme Court of India, the Court recommended that proceedings be broadcast live. The lead petition was brought by a law student who found himself unable to access SC courtrooms to watch proceedings in person. Writing the majority opinion for himself and then chief justice, Dipak Misra, Justice AM Khanwilkar held that live streaming proceedings is part of the right to access justice under Article 21 of the Constitution. Further, publishing court proceedings is an aspect of Article 129, per which the Supreme Court is a court of record. Journalists, young lawyers, civil society activists and academics would all benefit from live streaming, the Court opined.

The petitioners and the attorney general, KK Venugopal, both agreed on the need for live streaming. The AG suggested “Comprehensive Guidelines for Live Streaming of Court Proceedings in Supreme Court”. The majority opinion generally agreed with the AG’s recommendations. It proposed live-streaming cases of constitutional and national importance as a pilot project, including Constitution Bench cases. Matrimonial cases and those involving national security could be excluded.

In his concurring opinion, Justice DY Chandrachud noted that open courts help foster public confidence in the judiciary. “Litigants depend on information provided by lawyers about what has transpired during the course of hearings… when the description of cases is accurate and comprehensive, it serves the course of open justice. However, if a report on a judicial hearing is inaccurate, it impedes the public’s right to know.”

Both the majority and the concurring opinion noted that internationally, constitutional court proceedings are recorded in some form or the other. In Australia, proceedings are recorded and posted on the high court’s website. Proceedings of the Supreme Courts of Brazil, Canada, England and Germany are broadcast live. The Supreme Court of the US does not permit video recording, but oral arguments are recorded, transcribed, and available publicly on http://www.oyez.org. And democracies aside, in China, court proceedings are live streamed from trial courts up to the Supreme People’s Court of China.

India stands alone amongst leading constitutional democracies in not maintaining audio or video recordings or even a transcript of court proceedings. Court hearings can be turning points in the life of a nation: ADM Jabalpur comes readily to mind. More recently, there are any number of cases where the Supreme Court’s judgments have changed citizens’ lives — Ayodhya, Aadhaar, Section 377, Sabarimala, NRC and the triple talaq judgments are among them. The court craft of legal stalwarts like HM Seervai, Ram Jethmalani, or Ashok Desai is already lost to future generations for want of recording. Documentation is essential to preserve our history.

Over the last few years, the Supreme Court has taken steps to make justice more accessible. The Court started providing vernacular translations of its judgments. Non-accredited journalists were permitted to live-tweet court proceedings. During the lockdown, journalists have been permitted to view virtual court proceedings in real time. If that technology is available, it could be extended to members of the public, who can then view court proceedings themselves.

Courts around the world have had to find new ways of functioning during the pandemic. For example, the US Supreme Court heard arguments over the telephone, providing an audio-streaming facility for members of the public to dial in. It seems likely that for the next few years, Indian courts, too, will have to adopt a combination of virtual and in-person hearings. This transition is itself a crucial moment in our legal history, and it should be recorded for posterity. Moreover, the SC must take advantage of as many modes of communication as possible — including the internet, social media, television and radio. This will enable it to reach a wide cross-section of Indian society.

The SC has chosen to play an influential role as an institution of constitutional governance. The public is rightly interested, and has a right to know, about court proceedings in constitutional courts as well as trial and appellate courts. Openness and transparency reinforce the public’s faith in the judicial system. As Swapnil Tripathi noted, “sunlight is the best disinfectant” — all the more important during a pandemic.

This article first appeared in the print edition on June 3, 2020 under the title ‘In the sun, and in the light’. The writer is a lawyer practising at the Supreme Court.