A fair-skin obsession in a country where the majority of people are brown is a lifelong training in self-loathing and discrimination.

A fair-skin obsession in a country where the majority of people are brown is a lifelong training in self-loathing and discrimination.

A little girl and her brother go to the market. They sniff purple flowers, post a letter in a red post-box, spy an orange cat peeking out from behind a basket of green bhindi, and watch their mother haggle with a fisherwoman in an ochre sari. These are images from a wordless picture book for children that artist-writer Manjula Padmanabhan made in 1986. What stands out in A Visit to The City Market (NBT) is the rich earth of the children’s skin, and the many shades of dark brown of other people, from coffee to chocolate to chestnut. For Padmanabhan, one of the most genre-bending English writers in India, the book was a milestone. “Those children are dark,” she told me in an interview in 2015. “Till then, I had been using — not pink, but a soft brown colour. And I suddenly thought: Why don’t I use brown? The full undiluted brown. It was very liberating. But I also realised that many people found it ugly.”

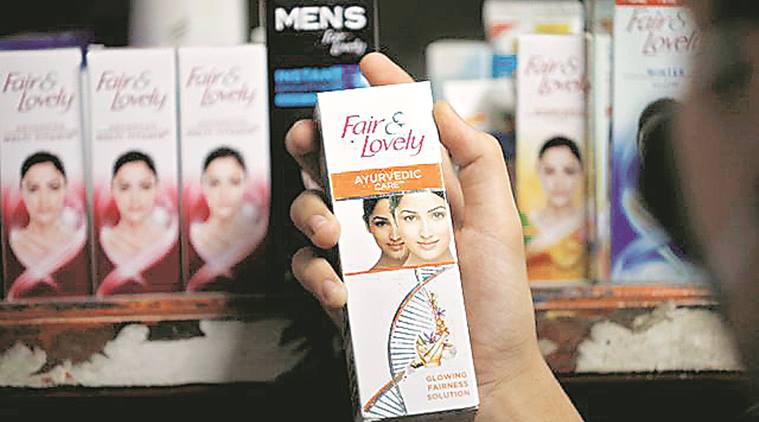

I came across the book years later, as an adult, long after I had stepped out of a childhood where the word for dark skin in Bengali — for my dark brown skin — was not just shamla, but moyla (dirty). The ads of Fair & Lovely, beaming in the message of “twacha ka nikhar” even in our unfamiliar-with-Hindi homes, therefore, did not need any translation.

A fair-skin obsession in a country where the majority of people are brown is a lifelong training in self-loathing and discrimination. It is tangled with broader structures of inequality, from caste to gender and class privilege, securing them in place with its softer, more invisible power. It works insidiously against the vulnerable, by chipping away at their self-worth.

For Hindustan Unilever, it has meant cold, hard profit — Fair & Lovely was made for Indian markets in 1975, and is now a Rs 2,000-crore business. In 2020, comes the turnaround, prompted by the introspection in America of ways by which apparently neutral cultural ideals of success and beauty perpetuate systemic bias. “We recognise that the use of the words ‘fair’, ‘white’ and ‘light’ suggest a singular ideal of beauty that we don’t think is right,” the company has said, while announcing its decision to drop “fair” from the brand name, and assuring us — in the face of 45 years of evidence to the contrary — that it is committed to “a global, inclusive portfolio of skin care brands”.

This is suspiciously less than a cosmetic change. More than black or brown lives, profit matters, which in an attention economy run by global social media algorithms, needs insincere social messaging to manage. Neither HUL nor other brands that reign over the Rs 4,000-crore whitening cream market has shown a desire to examine their role in the perpetuation of racist, casteist ideas of skin colour. Nor how deviously they have twisted ideas of women’s empowerment to sell unsubstantiated claims of melanin-suppressing “miracles”. In Fighting Poverty Together (2011), the writer Aneel Karnani, a professor of strategy at University of Michigan, cites HUL research that claimed “90 per cent of Indian women want to use whiteners, because it is aspirational, like losing weight. A fair skin is, like education, regarded as a social and economic step up.” In recent years, Fair & Lovely ads have showed women turning into successful teachers, cricket commentators or a lawyer fighting for “women’s rights” by lightening their skin. In one advertisement, a young working professional proves her worth to her father, who wishes he had a son, by transforming herself into a fair woman.

HUL and other brands are not the only ones guilty of colourist bias — from cinema to news television and advertising, there has been little challenge to the upper-caste, North Indian ideal of beauty and desirability. But, given the generations of dark women and men who have been made to feel unworthy because of the colour of their skin, it is not a burden they can shrug off.

Exploitative ideas of skin colour do not define you forever. I remember flipping through Padmanabhan’s book, as I read it to my daughter, lingering over a little brown girl dressed in a bright yellow — a colour I was ashamed to wear as a child — and her statuesque mother, a darker shade of brown, also in a yellow sari, and feeling a warm glow of affection: This is us. Not fair, but how lovely.

This article first appeared in the print edition on July 2, 2010, under the title “Not Fair, But How Lovely.” amrita.dutta@expressindia.com