That Rao is not celebrated more at the national level has several causes, including Rao’s own reticence.

That Rao is not celebrated more at the national level has several causes, including Rao’s own reticence.

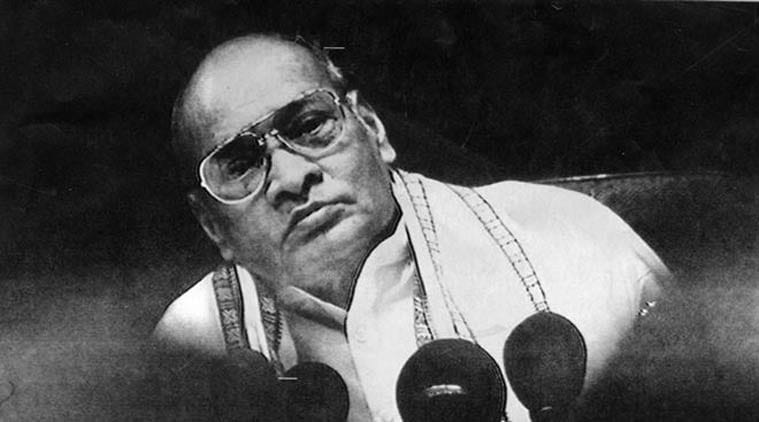

I landed in Hyderabad airport in late 2014, and hailed a taxi to meet Narasimha Rao’s youngest son. Having read a book on Deng Xiaoping, who led China’s transformation in the 1980s, I wanted to write a book on India changing in the 1990s, alongside the life of our Deng Xiaoping. Beyond that I didn’t know much of PV Narasimha Rao, prime minister of India from 1991 to 1996. Nor, it seemed, did most Indians, who remembered him only as an indecisive scholar who knew how to be silent in ten languages. But here I was, finally on his home turf (the new state of Telangana had been carved out from Andhra Pradesh just months earlier). Surely, here, people would know all about their most distinguished son. In my excitement, I asked my taxi driver about Narasimha Rao. Had he heard of him? Yes, came the reply after some thought. “He’s the man after whom a flyover is named.”

Reading about the TRS-run Telangana government’s recent decision to mark Rao’s birth centenary through year-long celebrations, I remembered that deflating moment. Finally, it seems, Rao will be popularised by more than just one eponymous flyover.

Telangana’s decision is partly motivated by the anger felt by at least some Telugu-speakers at the Congress’s treatment of Rao. As prime minister, Rao did much to undercut Sonia Gandhi — then a private citizen. But that hardly justifies the ignominy with which he has been treated by the Congress since: His dead body was refused entry into the party headquarters, his name and face have been erased from Congress offices, websites, and brochures. In the course of research for my eventual biography of Narasimha Rao, Half Lion: How PV Narasimha Rao transformed India, a TRS leader remembered the time when his party was in coalition with the Congress in what was then Andhra Pradesh. He wanted to erect a statue of Rao in Warangal, but the local Congressmen refused. “If the statue is built, then they have to go garland [it]. If someone takes a photo and Sonia madam sees it… they did not want that.” This relegation of Rao by the Congress resonates in a new state that sees itself as historically relegated. And it is perhaps this sympathy that the TRS now seeks to convert into votes.

But this vote-garnering aside, the primary reason why the Telangana government is honouring Rao is with an eye to history. What makes Telangana unique is not language, but the fact that its districts were all ruled by the Nizam, and continue to remain poor in comparison to coastal Andhra Pradesh. This is hardly a past that allows for a glorious myth of origin. Hence the need to erect local statues and elevate home-grown heroes. And Rao — from Karimnagar, just hours north of Hyderabad — is very much a son of their soil.

The only problem with this reason is that in his early years in Andhra politics, Rao was never in favour of a separate Telangana, preferring instead regional concessions within the framework of a united state. He was, in fact, made chief minister in 1971 both because he was from Telangana (to appease the separate state movement) as well as because he was against a separate state (thus assuaging the more powerful Andhra lobby). And once he lost power in 1973, he retreated to Delhi, becoming general secretary of the Congress, then central minister and, finally prime minister — all the while having little to do with his home state. For a man such as this to be resurrected as a regional icon does contain some irony.

The irony is even greater given that his two years as Andhra Pradesh chief minister were defined by failure. His one claim to fame — introducing sweeping land reforms — led to his own dismissal by then prime minister Indira Gandhi. His time in regional politics was so disheartening that Rao commenced writing a roman-à-clef — published decades later as ‘The Insider’.

The story: How an idealist, trapped in the smoke and mirrors of politics, ends up a failure.

In contrast to this flop at the state level, Rao’s term as prime minister in the 1990s was a game changer. He steered India’s foreign policy after the collapse of the Soviet Union; he created, for the first time, national level schemes in health, education, and employment guarantee; he was — in Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s words — the “true father” of India’s nuclear programme. And, above all, he navigated political landmines to push through economic liberalisation. In this last achievement, Manmohan Singh and Amar Nath Verma proved able subordinates. I detail these achievements in my biography, marshalling evidence to show that Rao was not just a silent onlooker, but an active manager of these changes.

What makes these reforms seem miraculous was that it was all done by a fragile prime minister. Rao ran a minority government, always at risk of a no-confidence motion that could force his resignation. And within this own party, he was forever destabilised by colleagues such as Arjun Singh,

ND Tiwari, and Sharad Pawar. He also had to keep Sonia Gandhi in good humour. For a leader as weak as Rao to bring about the transformation he did has few parallels in world politics.

There were mistakes, to be sure. As Union home minister in 1984, he chose to listen to a direct command from the prime minister’s office, and relinquished power over Delhi Police to the PMO, just ahead of the killing of Sikhs in the national capital. And his error of judgment in not dismissing the Uttar Pradesh state government before the 6th of December 1992 has haunted India since. But these stains aside, the sheer scale of Rao’s national impact makes him, in my opinion, India’s most consequential prime minister.

That Rao is not celebrated more at the national level has several causes, including Rao’s own reticence. But the chief culprit is his own party, unwilling to highlight any prime minister who does not come from one single family. Given this silence in New Delhi, Hyderabad’s decision to extol Narasimha Rao is to be welcomed. But it is a distortion of history. In the ultimate analysis, Rao belongs to all of India.