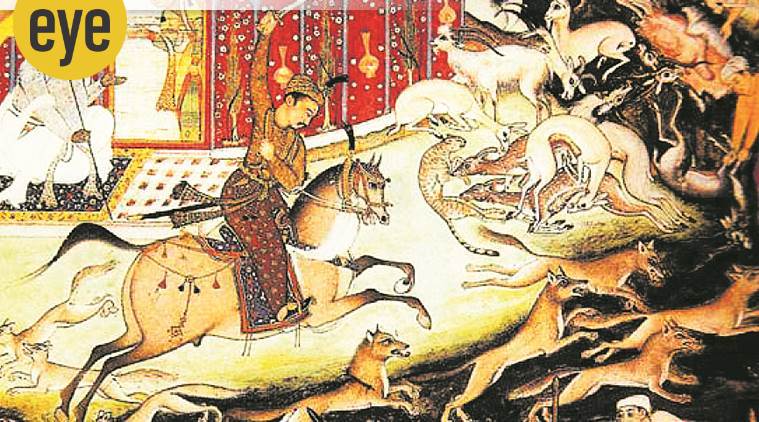

A painting depicting Akbar during a Qumargha hunt, which served to demostrate the emperor’s wealth and power. (Courtesy: Aleph Book Company)

A painting depicting Akbar during a Qumargha hunt, which served to demostrate the emperor’s wealth and power. (Courtesy: Aleph Book Company)

Author: Ira Mukhoty

Publisher: Aleph Book Company

Pages: 624

Price: Rs 799

From the zenana in your second book to the monarch who would become the face of the dynasty, what drew you to the Mughals in the first place?

The Mughals are very close to us in time. Only around 250 years separate us from their glory days, following which they continued to exist, diminished, for another 100 years. So in a very physical, immediate sense, the legacy of the Mughals is all around us. It can be seen in the buildings that litter the landscape of India, in the clothes we wear, the attar we use, the words that seep into our vocabulary, the ingredients in our kitchens. It is even there, in the faux-Shahjahani arches and overly-creamy dishes served in ‘Mughalai’ restaurants in watery British towns.

In my first book, Heroines (2017), I encountered the story of Jahanara Begum, Shah Jahan’s daughter. I was struck by her independence, wealth, her search for meaning outside of her opulent lifestyle. That led her to the Sufi path and the two biographies she wrote glow with the ambition of being taken as seriously as her brother Dara Shukoh, and her father, and not allowing her gender to undermine her. I found her message very moving, given that her memory had almost completely been erased, and that brought me to write Daughters of the Sun (2018). Since it was a re-evaluation of the zenana of the ‘Great Mughals’, a fascination for Akbar was inevitable. Akbar casts a huge shadow on Mughal history and on India as it is today. At the same time, there is a great deal of myth-making that inevitably accompanies such a personality. I thought it would be an interesting exercise to re-examine Akbar and his legacy using some fascinating new insights from art historians. Despite the fact that Akbar is such a talismanic figure, not nearly enough modern biographies in English have been written over the past few decades.

How do you react to the present-day vilification of the Mughal dynasty?

The vilification of Mughal history is, unfortunately, a product of a colonial legacy. It is the British who began speaking in terms of a pristine, unsullied earlier ‘Hindu’ era to distinguish from the later ‘Muslim’ one, as separate entities, in the 19th century. This was done to justify their own incursion into Hindustan but, unfortunately, this narrative continues to gain traction. Identities were never so simplistic as Hindu or Muslim, or indeed Christian, Jain, Buddhist, Parsi, etc. Identities were complex things, shaped by clan loyalties, geography, language, culture, etc, with religion being one of many factors, often not even the most important one. Which is why, I believe, it is all the more important to write narrative histories for the lay person, so that these nuances can be made easily accessible for interested people.

Would you say Akbar was the first of the Mughals to have a nuanced understanding of the syncretic nature of India? Is that why he eventually moved away from the scorched-earth policy of his Chittorgarh siege?

Akbar was the first to respond to the diverse nature of Hindustan and he made that response the very scaffolding of the empire. Both Babur and Humayun were already aware of this diversity and also quite pragmatic about the need to work with a non-Muslim majority. They both had a large number of Hindu soldiers in their armies due to their Timurid legacy, which was entirely practical when it came to religion. But neither ruled long enough to translate that into a coherent response. Akbar did, and that was part of his genius — to understand the complex nature of Hindustan and to create a system of administration, in which all members were invested in the system. People would not be rewarded or punished because of their religion, but through their talent and abilities.

The cover of the book ‘Akbar: The Great Mughal’

The cover of the book ‘Akbar: The Great Mughal’

The siege of Chittor came early in Akbar’s reign (1567-68), when he was yet to formulate a clear policy. He was still facing challenges on all fronts. It was the very brutality of Chittor that allowed Akbar to then use his power as a deterrent. It was only after the fall of Chittor and Ranthambore that many previously recalcitrant Rajput clans joined the empire, bringing lasting peace. So, Akbar may have viewed it as a necessary stage in the formation of a large, wealthy and stable empire.

Akbar’s reign began with a pandemic and there was another epidemic after his Gujarat campaign (1572-73). How did he respond to these medical challenges?

There have been famines, followed by epidemics, throughout history. Famines were frequent and led to widespread deaths, which then caused diseases. The people seemed to have an awareness that contagion could be spread through contact because there are accounts of entire families dying together in their homes because they locked themselves in. As far as Akbar is concerned, there is an account of a famine towards the end of the 16th century in Srinagar. Akbar took active steps to alleviate suffering — he set up food kitchens, abolished more than 50 harsh taxes and began the construction of a fort on Hari Parbat, for which hundreds of paid labourers were employed so that they had money for food.

You’ve dealt with the independence of the Mughal women and Akbar’s sensitivity to them, but during his reign, the assimilation with Hindustani culture slowly invisibilised them. How do you explain this dichotomy?

When Akbar married his Rajput wives in a bid to stabilise the empire, he was very young. The influence of the elite Rajput clan culture on the young Padshah was, therefore, substantial. One of these influences was very probably a desire, like the Rajput clans, to ‘invisibilise’ women behind a stricter concept of purdah and a fixed and defined zenana space. At the same time, Akbar also sought to bring order and structure into all aspects of Mughal life and society. If you go through Abu’l Fazl’s Ain-i-Akbari, you will see that there are elaborate procedures noted down for a range of activities, almost baffling in their minutiae, from rules for the feeding of the royal elephants to the keeping of the royal tents. In a sense, the ‘ordering’ of the female component of the Mughal royal family fell within this same framework. It did not, in any way, suggest that Akbar altered his view towards women, which remained empathetic and caring. He continued to challenge prevailing attitudes towards women, whether it was the practice of sati or the stigma against widow remarriage in Hinduism or the discriminatory laws of inheritance in Islam.