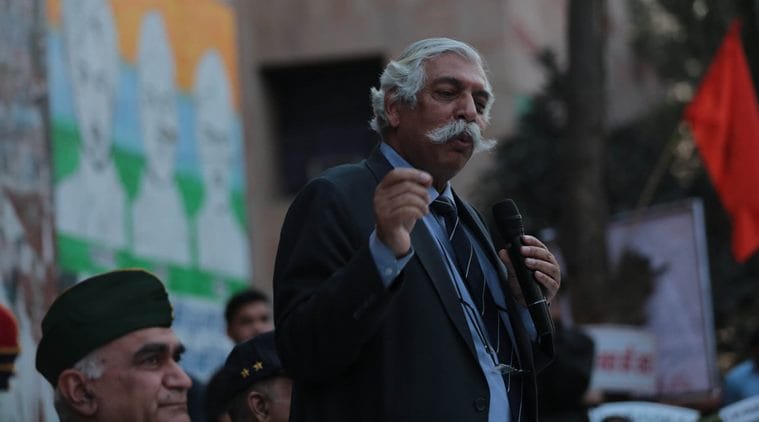

Major General GD Bakshi at an event in New Delhi (Express File Photo by Tashi Tobgyal)

Major General GD Bakshi at an event in New Delhi (Express File Photo by Tashi Tobgyal)

By Navneet Sharma

“If history and science has taught us anything, it is that passion and desire are not the same as truth.” — E O Wilson

Those who don the historian’s hat are expected to unearth, collect and present facts which make a coherent and cogent narrative. A historian also must have historical sensibility and historical mind. Though history is known as story of the past, yet it is not a story, but a re-construction of the past based on evidences and sources.

Before going into the appreciation of historical sensibility and historical mind of G D Bakshi and the invitation extended to him as historian by the vice chancellor of the university, one should acknowledge that the students and faculty of Centre for Historical Studies, JNU have issued press releases distancing themselves from the organisation of this event.

Bakshi has had a long stint with the Indian army. He is a decorated officer and has held important positions in the defence establishment. His vast experience must have contributed to his understanding of the nuances of battlegrounds, weapons and fighting. But neither his academic achievements nor his professional engagements qualify him enough to deliberate upon history, that too ancient history.

He was invited to speak about a book that he has written whose Kindle edition was launched recently, The Saraswati Civilisation: A Paradigmatic Shift in Indian History. The book’s description suggests that this is the “authentic” Indian history for which evidence, discoveries and facts have been brought together by the author with the help of sources ranging from satellite imagery, geology, hydrodynamics, textual hermeneutics and DNA research.

Despite his demanding career in the defence establishment, Bakshi could find the time for exhaustive and extensive research in ancient Indian history. He has also done research in modern Indian history and has attempted to answer another question which has baffled historians for long — Gandhi or Bose, who got the Indians their freedom.

His numerous publications reflect his varied concerns ranging from the Mahabharata, China to environment and ecology; they can embarrass any full-time social scientist.

History writing is a concerted effort and a research enterprise. A historian is expected to have historical consciousness, historical mind and historical sensibility. Historical consciousness is about being alive to the historicity of the facts. A historian must be conscious of the difference between fact, fiction and factoids.

A fact is observed by a historian from the vantage point of the historiography that s/he is trained in and influenced by. Facts can be drab and dry but they must be allowed to speak for themselves rather than a historian putting words into their mouth. Historians must be conscious that ideological leaning do not compel them to see a factoid as fact.

Jorn Rusen’s famous typology of historical consciousness not only indicates how people think about history and themselves, but it’s also about the pedagogical possibilities of historical culture. Rusen gives four categories of consciousness with historical constructions — traditional history, exemplary history, critical history and genetic history.

Bakshi seemingly believes in exemplary history in which the past is used to instruct contemporary action and belief. The search for the lost river Saraswati/Sarsuti and the huge amount of money spent by the government since 2014 and the establishment of the Saraswati Heritage Development boards by some states is not only about equating Harappan Civilisation to Rig Vedic society but also to conform the narrative of Aryavart and the Akhand Hindu Rashtra.

One may agree with Tom Griffith’s observation that history can be constructed at the dinner table, back fence, or in parliament or at the street, and not just in the tutorial room or at scholars’ desk. Through there cannot be any hierarchy in the construction of history, the discipline must be informed by the methodologies which are more consistent and transparent.

Scholars like Romila Thapar and Irfan Habib suggest that Saraswati may be derived from Haraxawati, a river in east Afghanistan. This space, however, cannot be used to settle an academic argument about the existence or non-existence of mighty river and its disappearance or the narrative that traces it to the Rig Vedic literature. It is concerned about how this alternative narrative, crafted by forgoing the difference between fact, fiction and factoid, is to used evolve exemplary historical consciousness that pronounces the otherness of Muslims in India.

A historical mind is steeped in history but not confined into it. A historian must be ready to accept criticism and accept that there can be several causes for events. A historical mind must be trained in historical thinking. Stephane Lévasque differentiates between two different ways of understanding history as “memory-history” and “disciplinary-history”.

Memory-history is about transmitting historical knowledge and is centered on facts and their veracity whereas disciplinary-history is procedural history, where the first question is why certain facts get the status of facts. When an educational institution invites a story-teller who wants to talk about history, it does disservice to discipline-history, where the process and procedure of construction of historical knowledge is more sacrosanct than the narration and the narrator.

The past is intertwined with present and lays out possibilities for the future. If we believe that those who do not learn from history, they are doomed to repeat it on themselves then we must also believe that if we learn “wrong” history we are doomed to repeat it twice, once as wrong and then as right history. A historian must have the historical sensibility not to create wedges where there are none like between Gandhi and Bose or Nehru and Patel. Such flawed historical sensibility also caters to us-them politics and widens the rift between Hindus and Muslims.

It’s a cliché that we write our own history. But history is something which is created with conflicts, revolutions and discoveries and inventions. In the rush to defend our vantage points we label historiography as colonial, nationalist or subaltern. Historians and history students, like those at JNU, should be aware about such nuances. Else, we will not be able to save historical knowledge construction from turning into indoctrination. The history student and the pedagogue must see through this artifice or soon we will be learning that Taj Mahal is actually a Tejo-mahalaya, a temple for Shiva.

The writer is faculty, Department of Education, Central University of Himachal Pradesh. The views expressed are personal