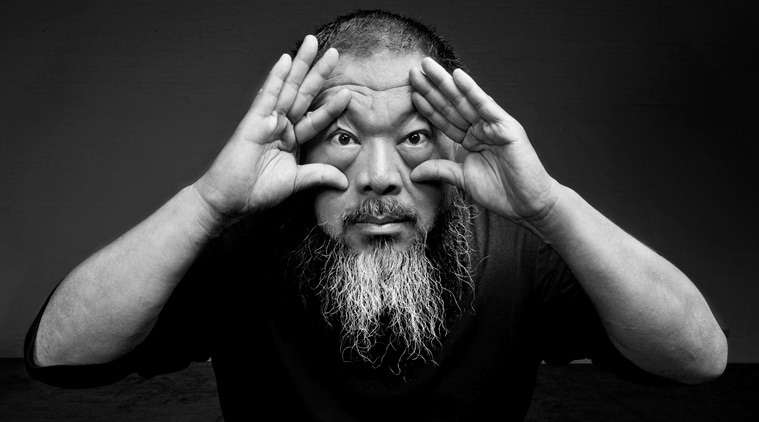

Ai Weiwei left China in 2015 and now lives in Cambridge, UK. (Photo: Ai Weiwei Studio)

Ai Weiwei left China in 2015 and now lives in Cambridge, UK. (Photo: Ai Weiwei Studio)

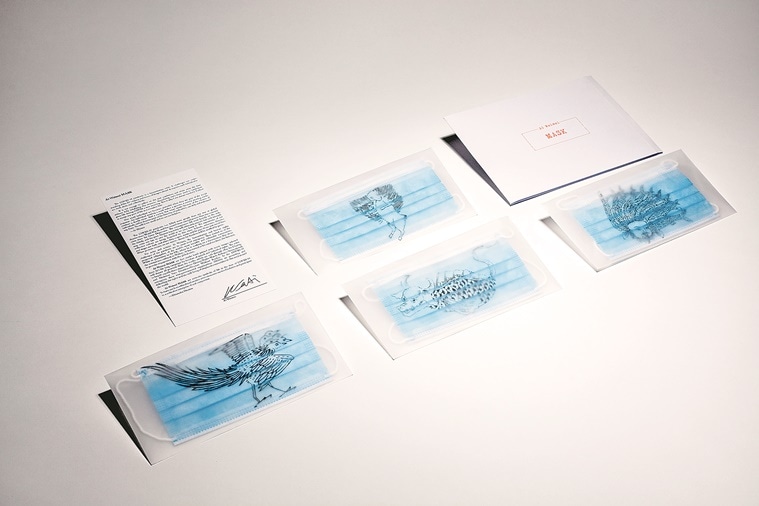

In a post on Instagram, accompanying a picture of a mask from the Ai Weiwei MASK project, you wrote: “The COVID-19 pandemic is a humanitarian crisis. It challenges our understanding of the 21st century and warns of dangers ahead.” Could you elaborate?

The coronavirus pandemic has revealed some very specific characteristics of this time. First, this is a global issue. It was triggered and spread early on by China and then spread everywhere else. Similar outbreaks have happened before in China and in other regions, such as in Africa and Europe, but never has it spread all over in such a fashion. Second, the disease has locked down the global economy and has put all other discussions aside.

No country has come out with the right or clear response to this disease. The consequences of this global pandemic are still unknown. We are still in the middle of it. We also do not know if it will come back, or whether another similar crisis might occur during or after Covid-19 — what is ongoing in the United States is an example. That is why I say it is a humanitarian crisis, rather than being a simple virus.

Sunday Long Reads| Of art, the legacy of Basu Chatterjee, food, insects, books, and more

Masks from the Ai Weiwei Mask project (Photo: Ai Weiwei Studio)

Masks from the Ai Weiwei Mask project (Photo: Ai Weiwei Studio)

The motifs on the masks come from your iconic works — including the rebellious middle-finger, handcuffs and a surveillance camera. Do you feel the scale of the pandemic is also impacted by the infringement on free speech and human rights, particularly with regard to how China has responded to the crisis?

Any kind of crisis may bring about different outcomes, but almost all crises allow those in power to increase their strength in controlling the people. During times of crisis, those in power expand their control in the name of maintaining stability and the people become even weaker. Often, the first task of any power after strengthening their control—whether democratic, authoritarian or otherwise—is to cover up or control the information, to suppress free speech, independent voices and the independent press. Now, more than ever, the freedom of speech and human rights are under attack globally. State surveillance has become much more sophisticated, such as what is happening in China where every citizen has been logged into the system and identified through big data. In human history, we have never had such a well-tuned and widespread system, where nobody is exempt from surveillance.

I lived under the pressure of a society that lacks justice and free speech. As an artist, I have fought for freedom of expression and against authoritarian societies. That is why my so-called iconic works still reflect the current condition.

In February, you were in Rome, working on the direction of a production of Giacomo Puccini’s Turandot, when things began shutting down in Italy. What was your experience? In one of your Instagram posts, you said: “Coronavirus is like pasta: the Chinese invented it, but the Italians will spread it all over the world.”

That was a joke an Italian friend told me. It reflects an interesting point: the Italian government was the first European nation to sign onto China’s Belt and Road initiative. That policy has bound the Italian political situation tightly to China. The reason is understandable. It is not because both nations love pasta, but rather because they both have to survive. China provides an opportunity and this has worked well, ensuring its ideology is shared alongside the divided and broken values of the European foundation.

The Italians were the most badly affected before the UK, France, Spain, and other nations in Europe. We were at the end stages of rehearsals for Turandot. Ironically, the opera is about a Chinese princess who attracts admirers from all over the world, intent on marrying her. It reflects the current condition so well. China is so beautiful, but also cruel. None of the suitors succeed, but one man still tries.

At the last moment of rehearsal, all the actors on stage were dressed in white full-body suits, such as the ones worn by those combatting the pandemic. I struggled with this. Did I go too far to reflect the current political situation in this classic opera? My production also reflected the global migration crisis, the Hong Kong uprisings, and, at the end, it touched on the coronavirus. During that last rehearsal, the opera’s superintendent came and told me we had to shut down.

With your team members in Wuhan, you are working on a documentary on Covid-19. Tell us about it.

My first documentary was made long before I became a political or cultural figure. It was called Eat, Drink, and Be Merry (2003) and filmed during the SARS outbreak. That film gave me the pleasure of recording human society’s behaviour, including its politics and daily life, how society reacts to danger, death, loved ones taken away and never seen again. So those things you would never see during peaceful or “normal” times, but always clearly reflected in times of crisis. That is the most attractive for anyone who is trying to understand more about themselves and their relation to their time and environment.

We started to make the documentary about Wuhan while concurrently producing the opera. The large time difference between China and Europe resulted in us working day and night. During the day, we rehearsed the opera. At night, we watched new footage, gave notes on direction, such as what to shoot and how to shoot. This was very intense, but it worked out well.

The film is not a political statement. There is no argument in the film. It is the most honest presentation I can make about Wuhan. I am Chinese and I know China very well. My mom and relatives are still in China. By no means, do I want China to be hurt, but at the same time I really want China to learn what kind of mistakes it has made during this whole pandemic.

While the trade war between the US and China has been ongoing, do you think the feud over coronavirus and the global backlash building against China will alter the world order or even bring a change inside China?

That is very difficult to predict. Things should change with or without the virus. China is a fast rising political and economic power, in strong competition with the West and especially the United States. The US has sensed the challenge. China has clearly denounced the Western values established during the last century. China employs a state-capitalist system with communist tactics. China is a Transformer-like creature that the West cannot fully imagine. It is multifunctional, impossible to describe, and cannot be measured with the same standards. At the same time, it is under the most restricted control and driven by a clear vision and purpose.

If the West continues to play in the same manner as before, by exploiting China’s weakness to profit, that it can deal with the China of today.

It’s very hard to say how much the US and the West have learned because the answer is very clear. They likely knew long ago, because the West, and especially the US, is led by ruthless capitalists. The so-called new world order is a corporate-authoritarian ideology. Under this kind of thought, China, India, Brazil, Mexico and many other places are necessary for the growth of the so-called global economy, but really it is about vicious capitalism, greed, and a lack of principles.

The US, under the current administration, has clearly illustrated the possible danger with China, but again the argument is: Who is first? Under this idea of “America First,” the only thing they are still trying to protect is the superiority of one super power over another. There is no philosophical thinking, no humanitarian values discussed, rather they are simply using it as a tactic to attack one another.

Today, with the most unimaginably capital-manipulated world, China is no longer China, just as the United States is no longer the United States. China has successfully integrated deeply into the world economy. China has invested heavily in future technology and their interests are represented in the US government and on Wall Street. That will not change as long as there is profit to be made, and China will continue to offer profit to the investor class. This is not an import-export tax issue, it is not even about who is first or who will dominate, but rather a battlefield about what kind of future we are stepping into and what kind of crises await us.

What is the role that artists should play at a time like now?

Who is the artist? A real artist should question that role, if that role exists. The artist should question that role every day. An artist is not a firefighter, or a doctor working in the intensive-care unit. An artist is concerned with human awareness, emotion, and imagination. Any artist who doesn’t care about the crisis our society is facing is not an artist, but someone decorating and trying to profit from the existing rotten system.

You have been working on a documentary about the protests in Hong Kong. How do you perceive China’s newly passed national-security bill on Hong Kong?

I have been repeating the same message since I left China in 2015 and began to pay attention to the global flow of refugees. That is when I put China on the map of the global political condition. China’s existence is proof of subversive principles toward Western values. Hong Kong is part of that Western bloc. Its promised 50 years of autonomy under One Country, Two Systems guarantees that it still enjoys its protected freedoms. China will never give up Hong Kong. It is not a matter of honour or pride, but one of deep principle. Just as China will also never give up Taiwan. That means it will take control by any means necessary. It is an authoritarian state so it has propaganda and the military, but besides that China has no other skills to achieve this. It just so happens those two things are often enough. I don’t think the international outcry will affect China. If it did, China’s brutal regime would have been stopped during the clash at Tiananmen Square 31 years ago. Both the West and China understand this.

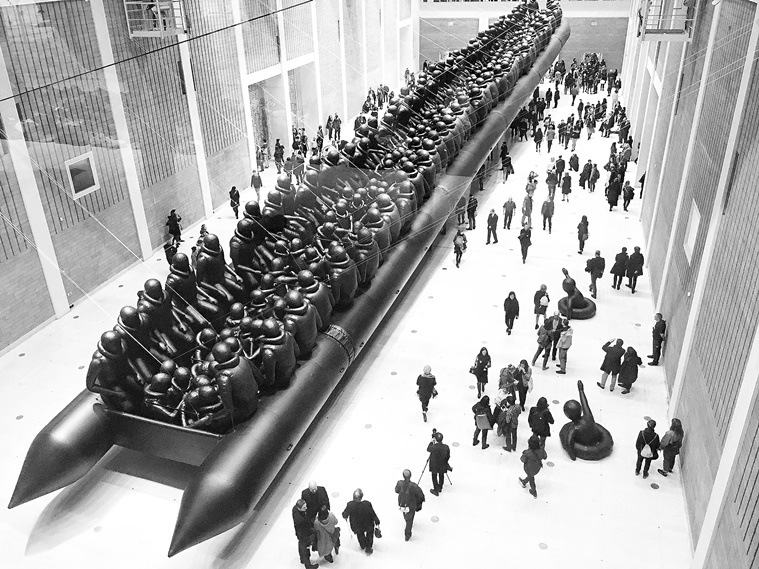

You have announced a new book based on the 2017 documentary Human Flow, which recorded your interactions with over 600 refugees and aid workers across 23 countries. Several of your recent works, including Laundromat (2016) and Law of the Journey (2017) have also reflected on the global migrant crisis. You have mentioned how “the refugee crisis is not about refugees, rather, it is about us.” Do you feel our failure to understand or accept this has worsened the crisis?

Any human crisis from the past, present, or future requires the stupidity of humans. We are the only ones creating these crises, leading to tragedies like the more than 70 million global refugees, a number continuing to grow due to all kinds of environmental issues, disease, and famine. I don’t think that those living in privilege, such as those in the West, give a damn about people elsewhere suffering inhumane conditions.

Law of the Journey (2016) was a hat-tip to the refugee crisis (Photo: Ai Weiwei Studio)

Law of the Journey (2016) was a hat-tip to the refugee crisis (Photo: Ai Weiwei Studio)

Last year, you shared your experience of racism in Germany, where you stayed for four years, before moving to Britain in 2019. What direction will increasing neo-nationalism and xenophobia being reported across the world lead to in the near future, according to you?

I left Germany not because I didn’t like German taxi drivers as the German media liked to say. That is a perfect example of how that media operates. They said taxi drivers are not Berliners and Berliners are not Germans, which was a ridiculous and racist argument. Germany is deeply immersed in an authoritarian mindset. They have an unforgettable and unforgivable history. Still, while that ideology has strong boundaries, they shift that ideology with regard to China.

If you don’t understand Germany, you should look at China. It is a mirror to Germany, and the Germans have stated clearly that the future of German industry is in China. China even bought 30 per cent of Deutsche Bank. Huge companies such as Volkswagen depend on the Chinese market. That tells you why German politicians shy away from any problems raised about China, such as the coronavirus or the Hong Kong and Taiwan issues.

They have played this skillfully. Annually, they host a human rights talk between the two nations behind closed doors that satisfies both sides and gives a fake image to the world. But I think both nations underestimate the judgement of the people. It is shameful to give up principles, to sacrifice human rights and freedom of speech, in order for corporations to profit. We all know it and it has to be clearly stated. It will be written in history, another shameful page in German history.

You, too, have been displaced from your own country; as a political dissident it is rather unsafe for you to go back, but do you ever feel the urge? You were also displaced during childhood, when your father (poet Ai Qing) was declared an enemy of the people and sent to a labour camp for reform, where your mother, you and your brother also stayed with him. How did that experience shape you?

Safety, a sense of family and social distance were never issues for me. I was born in danger and grew up in it. I don’t know what safety is. The only unsafe areas are when I see corruption and blindness in humanity’s intellectual state. That presents a clear danger. Not the virus, not mafias, not international corporations or political structures. I am perfectly safe in my mind. Nothing can destroy that.

I don’t think it is unsafe for me to go back to China. I did feel unsafe when they put me in solitary confinement and my voice disappeared. It is not that I want others to hear my voice, but that I need to hear my voice, to see the social response, and to recognise my life as a human being. Very often this is misunderstood. We are not talking about this at the same level. If they arrest me, I don’t think I would be unsafe. My understanding of well-being is also different.

A detail from his 2013 work, S.A.C.R.E.D (Ritual)(Photo: Ai Weiwei Studio)

A detail from his 2013 work, S.A.C.R.E.D (Ritual)(Photo: Ai Weiwei Studio)

In 2011, you were arrested and held for 81 days without charge. I believe when you told your interrogators that you are an artist, they did not believe it. Why was that the case?

I don’t blame the interrogators because they come from a military background. They would not believe that someone making sunflower seeds is an artist. With most of my works, it is not only the interrogators who don’t believe they are artworks, but my own mother doesn’t believe it either. Every time she mentions my work, she can’t hold in her laughter. She is proud that I have been brave and fought for those who have no voice, but she can’t believe what I have done is art.

The natural conclusion that the Chinese authorities reached was that I was made popular because I represent Western ideology and anti-China forces were trying to promote me. I tried to explain to them that there was no such thing as anti-China forces because everyone was busy, they were doing things practical. Being anti-China was not practical as China was getting bigger and stronger.

With that said, in the West, many in the established contemporary art system are either critical or hesitant toward someone like me because I am not playing the same game as they understand it. That is easy to accept. I am not one of their soldiers and proud not to be.

In 1979, you were part of one of the earliest contemporary avant-garde movements in China called the Stars Group. Soon after, you went to study at Parsons in New York, where you were exposed to Western art for the first time. You were in the US for more than a decade. How did that influence your art and notion of freedom?

My experiences in New York and the West taught me a lot. Not only about modern ethics or political conditions, but about what problems they reflect. It helped me to realise that personal freedom is essential for any so-called creativity.

Since 2005, you have actively used digital media platforms to communicate with your viewers. The lockdown, too, has seen several posts from you, including an image of a new sculpture. What role does social media play for you as an artist-activist?

Good question, it seems you know me well. Few would name 2005 as my starting point. Before that, I was doing architecture and was well-known in that circle. And before architecture, I was collecting Chinese antiquities, publishing underground books and curating art exhibitions.

2005 is the most important year. I can consider it my birth year. I touched a computer and learned how to type. Today, I spend more than 60 per cent of my energy online; 90 per cent of my interest is in social media. Even so, I still know very little. I’ve never used Weibo, for instance, but still social media consumes so much of my energy and imagination. It is about expression and communication. These two are the fundamental structures of my existence. Through expression, I see my existence. Through communication, I see an individual, someone you can identify with or oppose. That is my total environment and nothing is more important than what social media has given to my identity, existence and recognition of the self.