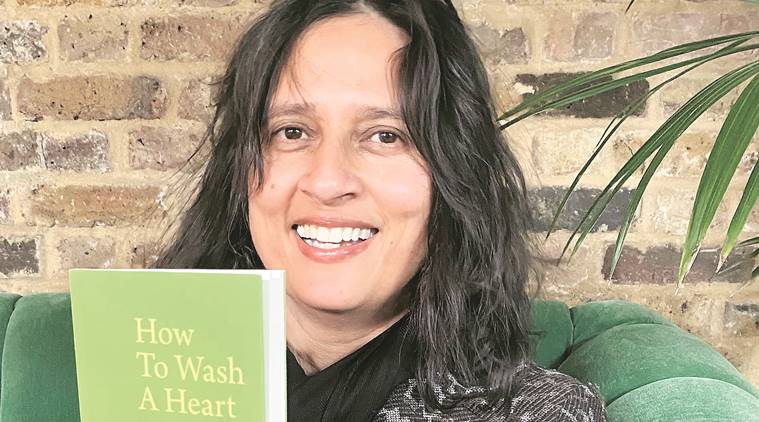

In Foreign Land: Bhanu Kapil with her prize-winning collection of poems (courtesy: Bhanu)

In Foreign Land: Bhanu Kapil with her prize-winning collection of poems (courtesy: Bhanu)

At a time when the entire world is learning the advantages of washing hands repeatedly and obsessively, a new poetry collection by British-Indian poet Bhanu Kapil, 51, aims to teach you how to wash a heart and make visible what is invisible. How to Wash A Heart (Pavilion Poetry, Liverpool University Press) is the sixth book of poetry/prose by Kapil, who is among the eight writers who have won the $165,000 Windham-Campbell Prize 2020, one of the worlds most lucrative awards.

Kapil, a British and US citizen of Punjabi origin, has lived in the United States for over 20 years. Having taught creative writing at Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado, for several years, she spent the last year as the Judith E. Wilson poetry fellow at the University of Cambridge, the UK. In the last few years, she has expanded the horizon of her artistic practice to include performances, improvised works, installations and rituals, among others. In her latest collection, Kapil explores the tenuous connections between an immigrant guest and a citizen host, drawing on her first performance at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London in 2019, which delved into the limits of inclusion, hospitality and care. The performance was a tribute to American postmodernist and feminist writer Kathy Acker. Its exhausting to be a guest/ In somebody elses house/ Forever, reads one of the poems in Kapils collection. What Kapil teaches us is that although the heart might be where desire, gratitude, even love exist, it is an organ to which, like a country, we may never fully belong, writes contemporary British poet Sandeep Parmar, in her blurb for the book.

Kapil says the question she wants to extend beyond her latest book is this: What do you do when the link between creativity and survival has been broken? In the last two decades, Kapil seems to have teased out literature from what she has seen and heard. In her fifth book, Ban en Banlieue (2015), she explored body and politics evocatively and ingeniously through the story of a nine-year-old girl, Ban, walking home from school as a riot starts to unfold in London. “I want a literature that is not made from literature. A girl walks home in the first minutes of a race riot, before it might even be called that the sound of breaking glass as equidistant, as happening/coming from the street and from her home, she writes in the book. Ban makes the decision to lie down, unable to figure out if the sound of breaking glass is coming from the street or from her home, and by the next morning, she is gone. She has become a part of the street and the night, but not the day, says Kapil. The trigger for the book, which is structured through several paratextual strategies an assemblage of notes, fragments, blog entries and vignettes was two-fold. The first arc develops an intense memory of April 23, 1979, when a riot unfolded in Little India Southall, Middlesex, in west London when an anti-racism protester, Blair Peach, was killed by the Metropolitan police, and the subsequent rise of the National Front, a far right group. That night, Kapil and her family had to lie on the floor, listening to the sound of screams and breaking glass. The poet was ten years old then. Those sounds, and the desire to connect the memory of the rise of the far right in the 1970s to the resurgent, xenophobic pulse of the present time, were the governing instincts of the work, says the poet. “What loops the ivy-asphalt/glass-girl combinations? Abraded as it goes? I think, too, of the curved, passing sound that has no fixed source. In a literature, what would happen to the girl? I write, instead, the increment of her failure to orient, to take another step. And understand. She is collapsing to her knees then to her side in a sovereign position,” writes Kapil in Banen Banlieue.

The other incident the book owed its genesis to was the gangrape and murder of Jyoti Singh Pandey in New Delhi in December 2012. “A year of sacrifice and rupture, murderous roses blossoming in the gardens of immigrant families with money problems, citizens with a stash: and so on. Eat a petal and die. Die if you have to. See: end-date, serpent-gate. Hole. I myself swivel around and crouch at the slightest unexpected sound, she writes. I wanted to write about the 40 minutes she lay on the floor of the world, next to the Mahipalpur flyover before anyone called the police. In fact, it was not possible to write these minutes, but only to think about them, to visit them, to keep attending to them, and to keep returning to the horror of what they must have been, says Kapil. Incidentally, on the day the Windham-Campbell prize was announced, the four convicts in the case were sentenced to death.

Kapils works often defy genres in the same way that she fills the outline of a particular nationality. An idea for a novel before its shattered, there on the bench next to the fountain, which is frozen, deconstructed, in the air/I cannot make the map of healing and so this is the map of what happened in a particular country on a particular day,” she writes in her fourth collection, Schizophrene (Nightboat Books, 2011).

Having never felt exactly English despite her British passport, and always a settler presence in the United States, no particular genre has ever felt like home to her as a writer. She could have added India to her Windham-Campbell nationality list, but refrained from doing so as she did not want to presume that India would think of me as a daughter. She recounts the memory of one summer in Chandigarh when her mothers neighbour told her, in a loud, carrying voice: Youre not Indian, youre English. Of course, in England, it was: Youre not English, youre…. Kapil says: I am not sure what my territory is. Perhaps its the never. Ive tried to pay attention to the sensations and the textures of the never-there, which is not, as it turns out, the same as the in-between. What about the ones who dont arrive, whose names are never written down in the document of place? says the poet, who was born in the UK in I968. In 1990, she completed one-year fellowship to State University of New York, Brockport, NY. Between 1991 and 1998, she travelled back and forth between the US and the UK, and returned permanently to the US in 1998. In 2019, she returned to the UK. Her19-year-old son went to university so she was able to leave US for the first time. She now has dual UK and US citizenship.

Teaching at Naropa University (and also at Goddard College in the US, where she teaches creative writing) has given her dual training in building works from the bottom-up.Writing like this is not typically something that results in winning a prize. Its as if someone has given me a prize for drinking 10,000 cups of tea in bed and writing in my notebook with a blue biro for the last 35 years, she says. At the University of Cambridge, she has been working out an idea of undeveloped writing, something she was also able to incubate at Städelschule, an art school in Frankfurt, with the students there. As a single parent and as a care-giver (with her sister) for their mother, the classroom was sometimes the only place she could be her whole self the one who wants to invert herself above a river or read at dusk the entirety of State of Exile (2003) by the Uruguayan novelist Cristina Peri Rossi, who moved to Barcelona (Spain) as a political exile. The memories I have of being in class are identical to the memories I have of being a writer in the world, says Kapil, who, together with Filipina-American poet Mg Roberts, is working on setting up an imprint for poets of colour as part of their start-up small press, Durga.

A day before the prize was announced, Kapil was wondering how she was going to manage when her Cambridge fellowship came to an end. How would she and her family afford care or the logistics of work and life commitments in both the UK and the US? The next day, Michael Kelleher, American poet and director of the Windham-Campbell Prize, called to inform her that she had won the prize. It is the first prize Kapil has won. To her, it seems to signify the difference between exhaustion and possibility. The fact that it comes at this time in history is profoundly meaningful. Knowing that I can care for my mother, that I can fulfill my duty to my family, is immeasurable, says Kapil, whose mind, as of now, is filled with several questions: From this place, can I blossom? Can I shine? Can I be of service to others? Can I complete something that remains to be completed?