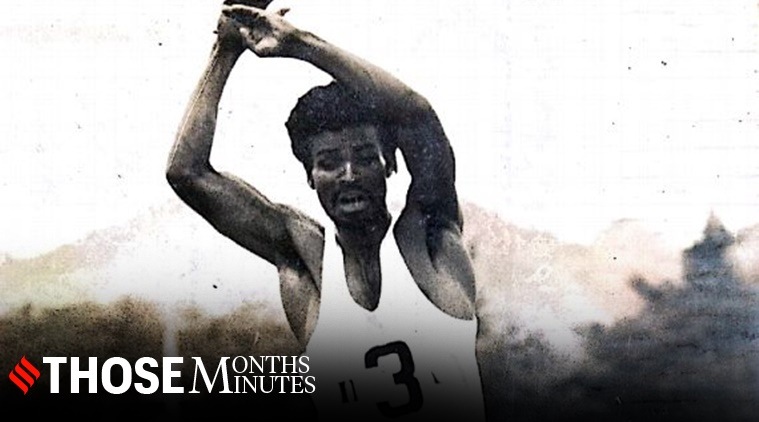

TC Yohannan’s 8.07m leap rewrote the national and Asian mark. Yohannan didn’t realise the magnitude of his achievement until he received a rousing welcome back in India.

TC Yohannan’s 8.07m leap rewrote the national and Asian mark. Yohannan didn’t realise the magnitude of his achievement until he received a rousing welcome back in India.

Every once in a while, former long jumper TC Yohannan receives a phone call from a journalist. And more often than not, they want him to narrate an incident that happened almost half a century (46 years, to be precise) back in Tehran, Iran.

When a call was made for this story, the first remark 74-year-old Yohannan made after the initial exchange was: “What do you want to know? I am neither a coach nor related to sports anymore.”

It’s hard not to picture him as one of those old, grumpy stars of yesteryear one often sees in sports movies. But two minutes into the conversation, all such misconceptions are dispelled.

“I have left sports a long time back but I’ll try to help you with whatever I know,” he says in an assuring tone.

What happened in Tehran at the 1974 Asian Games?

It takes Yohannan a while to build up to the event. He insists on narrating the incident that got him into sports, his training routine, and finally to the big day at the newly-built Āryāmehr Sport Complex now known as the Azadi Sport Complex. His iconic jump on 12 September 1974 not only earned Yohannan a gold medal at the Asian Games but also a national record that stood for 30 years.

How it began

“Do you know the incident that got me into athletics?” he asks. Young Yohannan had arrived home from school one day in soaking-wet trousers. The 12-year-old tried to sneak into the house but couldn’t escape his father’s watchful eyes.

“My friend had thrown me a challenge. There was a stream on the way home and my friend promised me to buy me a cold drink if I could jump across it. I failed,” he says. The next day Yohannan’s father took him to the same stream and asked him to try again, and after several attempts he finally jumped over the stream. That moment changed everything. “It’s only because of my father that I became an athlete.”

Training to be a champ

Soon Yohannan started excelling in school-level sports and eventually made it to the National Institute of Sports in Patiala. It was at this facility that he trained for the ’74 Asiad.

“The training for Tehran wasn’t anything different. For any major event, the training begins at least a year ahead. The first few months are spent on strengthening your body. The body needs to get ready for the grind and then only you hit the track. The period just before the competition is where it is most relaxed,” explains Yohannan, who has a diploma in mechanical engineering.

Yohannan’s day at the camp began at 5:30 in the morning and would end late evening. There wasn’t any special diet he followed. His shoes came from a local manufacturer and he had to change them often as the spikes would get worn out every second day.

“I didn’t need much. I was happy with the facilities provided. I used to avail the food at the mess and have some fruits and milk,” he recalls.

Yohannan, in his own words, isn’t a very emotional person. He refrains from using the words ‘struggle’ or ‘difficult’, often associated with any sporting miracle. “What’s difficult? If you put your mind into anything, you can achieve it. Back then, I had only one thing in my mind: athletics. I had no life outside it”.

Yohannan comes from a modest farmer family in Maranadu village in Kollam, Kerala. There weren’t any training facilities in his vicinity and taking up athletics wasn’t fashionable by any means back then. But that was soon to change.

‘Knew the track well’

In the run-up to the Asiad, Yohannan had landed a jump close to 7.80m and knew at the back of his mind that an 8m-plus leap was within reach. Yohannan had also taken part in an invitational meet just a year before the Asian Games at the very same venue. “I knew the track and pit very well. I had made mental notes and had markers that helped me. When I returned for the Asian Games, I was comfortable,” he says.

“On the day of the finals, it was like any other competition. I did my warm-up routine and was feeling good. Everything went according to plan, until…”

After his first jump, an old toe niggle resurfaced. Yohannan, 5 feet-8 inches tall, would make up for his relatively short height with an explosive take-off. But they came at a price. “It put a lot of stress on my toes,” he says. The moment his foot hit the board, he knew something was wrong. He had suffered a stress fracture in his big toe bone on the take-off foot.

It might seem like a major setback in the middle of an important competition. But Yohannan didn’t think like most. “In sports, you get injured all the time. I wasn’t scared at all. I just consulted my coach and the doctors and I was given painkillers. That part of the foot went numb after that, I couldn’t feel a thing. So I was good to go again,” he says, almost brushing off the injury like it was a tiny bruise.

In his second attempt, he managed 7.80m. In his fourth leap, he made his life’s best jump — an 8.07m leap that rewrote the national and Asian mark. Yohannan didn’t realise the magnitude of his achievement until he received a rousing welcome back in India.

“I was not surprised at all. I knew I had the potential to land a good jump like that,” he says with no excitement in his voice. The only time he probably displayed any emotion was when the national anthem was played while he was atop the podium.

“The stadium was jampacked and they played the anthem. The feeling was inexplicable. Those few minutes are the greatest reward any athlete can receive. I looked at the Tricolour being hoisted and my heart was filled with peace,” he says.

Yohannan record of 8.07 metres was finally broken after 30 years in 2004 by a Punjab police officer Amritpal Singh at the Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium in Delhi.

Yohannan is a content man and has no complaints. But there is one wish that will forever remain unfulfilled. “My father was not alive to see my greatest medal. But then, what can one do. The Tehran gold, like all my other athletics achievements, is dedicated to him,” he says while reiterating his father’s role in his career.

Sensing he might get emotional while talking a little more about his father, he quickly comes back to his natural self: “What else do you want to know?”