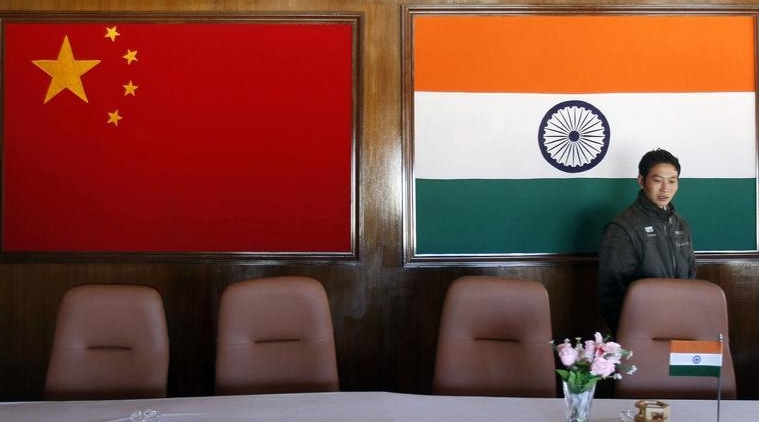

India-China LAC talks today LIVE updates: Officials cautioned against expectations of any immediate resolution, saying the Saturday meeting could be the first of several. (File photo)

India-China LAC talks today LIVE updates: Officials cautioned against expectations of any immediate resolution, saying the Saturday meeting could be the first of several. (File photo)

India-China LAC talks today LIVE updates: The commanders of India and China’s militaries Saturday held Lieutenant General-level talks in their first major attempt to resolve the month-long tense situation along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in eastern Ladakh. The Indian delegation was led by Lt General Harinder Singh, the general officer commanding of Leh-based 14 Corps, while the Chinese side was headed by the Commander of the Tibet Military District, news agency PTI reported. The meeting was scheduled to be held at 8:30 am but was delayed to 11:30 am.

The meeting comes a day after Indian and Chinese ambassadors joined a video call between diplomats of their border working mechanism Friday to underline that “the two sides should handle their differences through peaceful discussion” and “not allow them to become disputes”. Officials cautioned against expectations of any immediate resolution, saying the Saturday meeting could be the first of several.

Earlier sourced had told The Indian Express, the meeting would begin with the Indian side making the first submission, which will include asking both sides to maintain peace and tranquillity on the border, and to adhere to protocols and agreements signed by the two countries since 1993.

Many rounds of military talks between Indian and Chinese commanders on the ground have failed to break the stalemate where the soldiers of both sides are deployed against each other on the LAC.

Many rounds of military talks between Indian and Chinese commanders on the ground have failed to break the stalemate where the soldiers of both sides are deployed against each other on the LAC.

Indian and Chinese officials continue to remain engaged through the established military and diplomatic channels to address the current situation in the India-China border areas: Indian Army -- PTI

"Meeting between Indian and Chinese military commanders is going on at Moldo on the Chinese side of Line of Actual Control (LAC) to discuss the ongoing dispute along the LAC in Eastern Ladakh between the two countries," ANI quoted sources as saying.

Over the years, the Chinese have built motorable roads along their banks of the Pangong Tso. At the People’s Liberation Army’s Huangyangtan base at Minningzhen, southwest of Yinchuan, the capital of China’s Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, stands a massive to-scale model of this disputed area in Aksai Chin. It points to the importance accorded by the Chinese to the area. Even during peacetime, the difference in perception over where the LAC lies on the northern bank of the lake, makes this contested terrain.

In 1999, when the Army unit from the area was moved to Kargil for Operation Vijay, China took the opportunity to build 5 km of road inside Indian territory along the lake’s bank. The 1999 road added to the extensive network of roads built by the Chinese in the area, which connect with each other and to the G219 Karakoram Highway. From one of these roads, Chinese positions physically overlook Indian positions on the northern tip of the Pangong Tso lake.

By itself, the lake does not have major tactical significance. But it lies in the path of the Chushul approach, one of the main approaches that China can use for an offensive into Indian-held territory.

Indian assessments show that a major Chinese offensive, if it comes, will flow across both the north and south of the lake. During the 1962 war, this was where China launched its main offensive — the Indian Army fought heroically at Rezang La, the mountain pass on the southeastern approach to Chushul valley, where the Ahir Company of 13 Kumaon led by Maj. Shaitan Singh made its last stand. This was made memorable in Chetan Anand’s 1964 war film, Haqeeqat, starring Balraj Sahni and Dharmendra.

Not far away, to the north of the lake, is the Army’s Dhan Singh Thapa post, named after Major Dhan Singh Thapa who was awarded the country’s highest gallantry award, the Param Vir Chakra. Major Thapa and his platoon were manning Sirijap-1 outpost which was essential for the defence of Chushul airfield. The award was announced posthumously for Major Thapa, as reflected in the citation, but he was subsequently discovered to have been taken prisoner by the Chinese. He rejoined his unit after being released from the PoW camp.

Pangong Tso lake in eastern Ladakh has often been in the news, most famously during the Doklam standoff, when a video of the scuffle between Indian and Chinese soldiers — including kicking and punching, the throwing of stones, and the use of sticks and steel rods, leading to severe injuries — on its banks went viral on August 19, 2017.

It was a visual confirmation of what had been reported about the incident that took place on that Independence Day morning. In the Ladakhi language, Pangong means extensive concavity, and Tso is lake in Tibetan.

Pangong Tso is a long narrow, deep, endorheic (landlocked) lake situated at a height of more than 14,000 ft in the Ladakh Himalayas. The western end of Tso lies 54 km to the southeast of Leh. The 135 km-long lake sprawls over 604 sq km in the shape of a boomerang, and is 6 km wide at its broadest point.

The recent incidents at the Pangong Tso lake area between Indian and Chinese soldiers on the LAC involve a picturesque lake, mountains, helicopters, fighter jets, boats, eyeball-to-eyeball confrontation, fisticuffs and injuries. Even if all the ingredients of a thriller drama are present, this is a far serious business between two nuclear armed trans-Himalayan neighbours that has implications beyond the region.

The LAC mostly passes on the land, but Pangong Tso is a unique case where it passes through the water as well. The points in the water at which the Indian claim ends and Chinese claim begins are not agreed upon mutually. Most of the clashes between the two armies occur in the disputed portion of the lake. As things stand, 45 km-long western portion of the lake is under Indian control, while the rest is under China’s control.

ANI quotes Indian Army Spokesperson as saying: "Indian and Chinese officials continue to remain engaged through the established military and diplomatic channels to address the current situation in the India-China border areas."

If the Line of Actual Controlisn’t delineated soon, it will remain vulnerable to face-offs and India and China may end up deploying more troops there, just like it is on the LoC with Pakistan, said Gen (retd) V P Malik who was Chief of Army staff when the Kargil intrusion took place in 1999. Gen Malik, who led the Army in the successful eviction of Pak troops, said, in an interview to The Indian Express, that an aggressive China, besides nibbling at Ladakh, could also attempt to take control of Karakoram Pass and the area between it and Shaksgam Valley ceded to it by Pakistan. Read the full interview here

On May 22, Army chief General MM Naravane landed at the XIV Corps headquarters in Leh to review the situation in eastern Ladakh. The Army chief’s visit to the corps headquarters came a day after the Ministry of External Affairs hit back at Beijing over the LAC developments, saying “it is the Chinese side that has recently undertaken activity hindering India’s normal patrolling patterns” and “we are deeply committed to ensuring India’s sovereignty and security”.

The unprecedented high levels of tension at multiple locations in eastern Ladakh on the disputed India-China border, where Chinese soldiers have moved into Indian territory across the Line of Actual Control (LAC), has raised questions about the Chinese motives for this action. Most observers were eagerly waiting for Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s annual press conference on the sidelines of the Communist Party Congress for an explanation, but his 100-minute long presser in Beijing on Sunday did not mention India at all.

“The Chinese learnt from the public handling of the Doklam crisis. They thought India would be quick to brief the media, so they did it first and continued to do so. We were calm and measured, calling for discussions and negotiations. They are trying to avoid that kind of situation. Quiet diplomacy has space to produce results in these kinds of situations,” Gautam Bambawale, who was India’s ambassador to China from 2017 to 2018, told The Indian Express. Read More

The meeting between the top commanders of India and China has been delayed and is now likely to be held between 11- 11:30 am, said sources. XIV Corps Commander Lt General Harinder Singh is expected to meet his Chinese counterpart at the Chushul-Moldo border meeting point

The LoC emerged from the 1948 ceasefire line negotiated by the UN after the Kashmir War. It was designated as the LoC in 1972, following the Shimla Agreement between the two countries. It is delineated on a map signed by DGMOs of both armies and has the international sanctity of a legal agreement. The LAC, in contrast, is only a concept – it is not agreed upon by the two countries, neither delineated on a map or demarcated on the ground.

Independent India was transferred the treaties from the British, and while the Shimla Agreement on the McMahon Line was signed by British India, Aksai Chin in Ladakh province of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir was not part of British India, although it was a part of the British Empire. Thus, the eastern boundary was well defined in 1914 but in the west in Ladakh, it was not.

A G Noorani writes in India-China Boundary Problem 1846-1947 that Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel’s Ministry of States published two White Papers on Indian states. The first, in July 1948, had two maps: one had no boundary shown in the western sector, only a partial colour wash; the second one extended the colour wash in yellow to the entire state of J&K, but mentioned “boundary undefined”. The second White Paper was published in February 1950 after India became a Republic, where the map again had boundaries which were undefined.

Not for India. India’s claim line is the line seen in the official boundary marked on the maps as released by the Survey of India, including both Aksai Chin and Gilgit-Baltistan. In China’s case, it corresponds mostly to its claim line, but in the eastern sector, it claims entire Arunachal Pradesh as South Tibet. However, the claim lines come into question when a discussion on the final international boundaries takes place, and not when the conversation is about a working border, say the LAC.

Only for the middle sector. Maps were “shared” for the western sector but never formally exchanged, and the process of clarifying the LAC has effectively stalled since 2002. As an aside, there is no publicly available map depicting India’s version of the LAC.

During his visit to China in May 2015, PM Narendra Modi’s proposal to clarify the LAC was rejected by the Chinese. Deputy Director General of the Asian Affairs at the Foreign Ministry, Huang Xilian later told Indian journalists that “We tried to clarify some years ago but it encountered some difficulties, which led to even complex situation. That is why whatever we do we should make it more conducive to peace and tranquillity for making things easier and not to make them complicated.”

As per Menon, it was needed because Indian and Chinese patrols were coming in more frequent contact during the mid-1980s, after the government formed a China Study Group in 1976 which revised the patrolling limits, rules of engagement and pattern of Indian presence along the border.

In the backdrop of the Sumdorongchu standoff, when PM Rajiv Gandhi visited Beijing in 1988, Menon notes that the two sides agreed to negotiate a border settlement, and pending that, they would maintain peace and tranquillity along the border.

Shyam Saran has disclosed in his book How India Sees the World that the LAC was discussed during Chinese Premier Li Peng’s 1991 visit to India, where PM P V Narasimha Rao and Li reached an understanding to maintain peace and tranquillity at the LAC. India formally accepted the concept of the LAC when Rao paid a return visit to Beijing in 1993 and the two sides signed the Agreement to Maintain Peace and Tranquillity at the LAC. The reference to the LAC was unqualified to make it clear that it was not referring to the LAC of 1959 or 1962 but to the LAC at the time when the agreement was signed. To reconcile the differences about some areas, the two countries agreed that the Joint Working Group on the border issue would take up the task of clarifying the alignment of the LAC.

India rejected the concept of LAC in both 1959 and 1962. Even during the war, Nehru was unequivocal: “There is no sense or meaning in the Chinese offer to withdraw twenty kilometres from what they call ‘line of actual control’. What is this ‘line of control’? Is this the line they have created by aggression since the beginning of September?”

India’s objection, as described by Menon, was that the Chinese line “was a disconnected series of points on a map that could be joined up in many ways; the line should omit gains from aggression in 1962 and therefore should be based on the actual position on September 8, 1962 before the Chinese attack; and the vagueness of the Chinese definition left it open for China to continue its creeping attempt to change facts on the ground by military force”.

The alignment of the LAC in the eastern sector is along the 1914 McMahon Line, and there are minor disputes about the positions on the ground as per the principle of the high Himalayan watershed. This pertains to India’s international boundary as well, but for certain areas such as Longju and Asaphila. The line in the middle sector is the least controversial but for the precise alignment to be followed in the Barahoti plains.

The major disagreements are in the western sector where the LAC emerged from two letters written by Chinese Prime Minister Zhou Enlai to PM Jawaharlal Nehru in 1959, after he had first mentioned such a ‘line’ in 1956. In his letter, Zhou said the LAC consisted of “the so-called McMahon Line in the east and the line up to which each side exercises actual control in the west”. Shivshankar Menon has explained in his book Choices: Inside the Making of India’s Foreign Policy that the LAC was “described only in general terms on maps not to scale” by the Chinese.

After the 1962 War, the Chinese claimed they had withdrawn to 20 km behind the LAC of November 1959. Zhou clarified the LAC again after the war in another letter to Nehru: “To put it concretely, in the eastern sector it coincides in the main with the so-called McMahon Line, and in the western and middle sectors it coincides in the main with the traditional customary line which has consistently been pointed out by China”. During the Doklam crisis in 2017, the Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson urged India to abide by the “1959 LAC”.