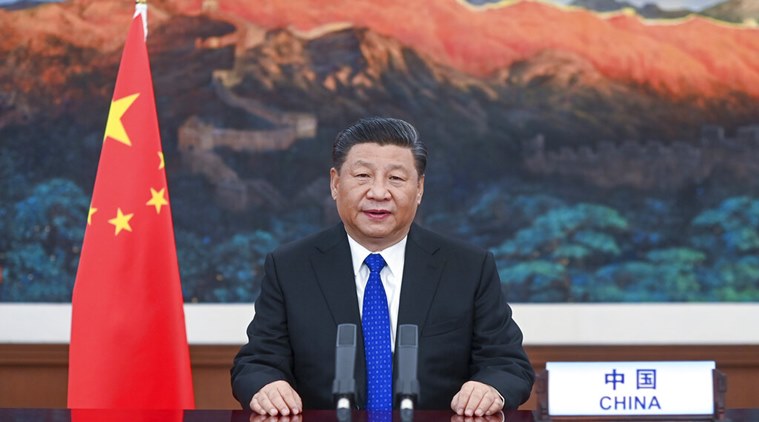

In this photo released by Xinhua News Agency, Chinese President Xi Jinping delivers a speech at the opening of the 73rd World Health Assembly via video link in Beijing, Monday, May 18, 2020.

In this photo released by Xinhua News Agency, Chinese President Xi Jinping delivers a speech at the opening of the 73rd World Health Assembly via video link in Beijing, Monday, May 18, 2020.

Over the last month, as Chinese and Indian soldiers face off in Ladakh and Beijing fights US-led global mistrust over its handling of the coronavirus, China’s top leadership has been actively engaged with countries in the south Asian region.

India, too, is engaged in aggressive Covid diplomacy. Prime Minister Narendra Modi held a virtual summit with Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison on Thursday, and earlier this week, he spoke to US President Donald Trump, with the conversation including the situation at the LAC. Foreign Secretary Harsh Shringla briefed his Russian counterpart about it in a conversation that also touched on Afghanistan and the pandemic.

According to the Ministry of External Affairs, Modi has spoken with leaders of more than 40 countries since March 11, when WHO declared a Covid pandemic. India has sent medicines to Indian Ocean countries such as Maldives, Sri Lanka, Mauritius, Madagascar, Seychelles, and Comoro Islands, and sent Covid aid to all South Asian countries, except Pakistan.

Tougher tightrope walk

In tensions with Pakistan, Delhi is able to dial SAARC capitals and make most of them fall in line. Given the stakes for them in balancing between the two powers, this might prove more difficult when it comes to China.

Aside from the March video conference with SAARC health ministers, Modi spoke with President Gotabaya Rajapaksa of Sri Lanka on May 23; and on May 25 with Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina of Bangladesh. His conversation with Prime Minister Kharga Prasad Oli was in April, predating the present crisis with Nepal over territory at Lipu Lekh. And he spoke to Afghanistan President Ashraf Ghani in March, when the latter was declared the winner of the presidential election.

Chinese diplomacy in this period, especially in India’s neighbourhood has been just as, if not more, pushy.

Chinese President Xi Jinping dialled at least three leaders of countries in India’s immediate neighbourhood to reiterate the importance of its bilateral relations with each, offering help and support in the fight against Covid, stressing the value it places on strategic and economic ties, and suggesting that Chinese infra projects interrupted by the pandemic in those countries should be resumed at the earliest.

On May 20, a day after the 73rd World Health Assembly adopted a resolution, calling for an investigation into the source of the virus and the working of the WHO, Xi called Sheikh Hasina.

India, Bangladesh and Bhutan were the three SAARC nations to add their names to the resolution, which was seen as anti-China though it did not mention it by name.

In his conversation with Prime Minister Hasina, according to a read out from China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Xi told Hasina that “China is prepared to help (with the) actual needs of Bangladesh,” for fighting Covid.

He described both countries as “each other’s important partners for development”, and said that it was “ imperative” that they “enhance their strategic partnership of cooperation and deepen Belt and Road cooperation” and move toward “gradual resumption of key cooperation projects and maintain the stability of the industrial and supply chains”.

With the Myanmar President, Xi spoke of hastening projects that are part of the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor, while offering continued support to fight Covid. The two countries marked the 70th year of their diplomatic relations.

Xi spoke of the “pauk phaw” (Burmese word for brotherly) relations between the two countries, built on “solidarity and mutual assistance and the spirit of a community with a shared future”, a readout from the Chinese foreign ministry said.

A week earlier, on May 14, Xi called Sri Lankan President Gotabaya Rajapaksa. “While ensuring good prevention and control of COVID-19, the two countries could gradually restore cooperation in various areas, steadily resume the major cooperation projects and take forward high-quality Belt and Road cooperation,” Xi said.

Rajapaksa also “expressed Sri Lanka’s hope to strengthen cooperation with China in areas of economy, trade, tourism and infrastructure, smoothly advance the Colombo Port City and other key projects under the Belt and Road cooperation,” according to the Chinese readout of the phone call.

Chinese envoy to Sri Lanka Hu Wei said in an interview to the Sri Lankan Daily Financial Times on May 27 that Chinese banks and other enterprises are providing strong support for the country’s economic recovery via financial, investment and other channels.

In Nepal, in early May, the Chinese envoy to Kathmandu, Hou Yanqi, engaged in shuttle diplomacy between Prime Minister Kharga Prasad Oli, and two other leaders of the Nepal Communist Party, Pushpa Kamal Dahal Prachanda, and Madhav Nepal, in an apparent attempt to patch up a rift in the party and avert a threat to Oli’s continuance in office.

At the time, Nepal foreign minister Pradeep Kumar Gyawali had said these were routine meetings facilitated by his ministry, as Yanqi wanted to convey China’s solidarity with Nepal in the battle against Covid.

Pakistan is where the India-China border spat has excited most interest. Both marked the 69th anniversary of their diplomatic relations on May 21 but without the annual fanfare because of the pandemic.

The Chinese envoy Yao Jing posted a video message on Twitter in which he said: “We are iron brothers and working together for our well-being and development, as well as for the promotion of regional peace and development. China appreciates Pakistan for its kind understanding & support of our friendship & cooperation.”

A week earlier, Pakistan’s upper house of Parliament, the Senate, passed a resolution lauding China, and the ties between the two countries.

The resolution, presented by Raja Muhammad Zafar-ul-Haq, leader of the opposition in the senate, and endorsed by both ruling and opposition benches, acknowledged China’s support to Pakistan to fight Covid that helped “saving lives as well as providing our health workers with testing kits, protective gears and ventilators.”