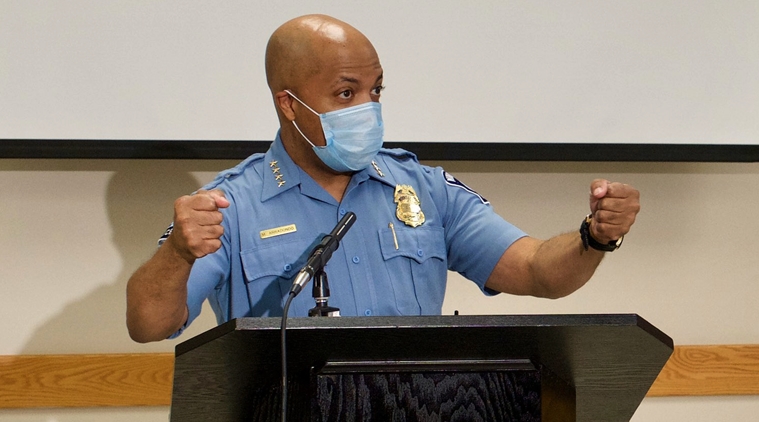

Medaria Arradondo has been in charge of the Minneapolis Police Department since 2017. (Source: Twitter/@MinneapolisPD)

Medaria Arradondo has been in charge of the Minneapolis Police Department since 2017. (Source: Twitter/@MinneapolisPD)

When Medaria Arradondo was tapped to lead the Minneapolis Police Department in 2017, he faced a public newly outraged by the fatal police shooting of a woman who had called 911 and still carrying deep mistrust from the killing of a black man two years earlier.

Many hoped Arradondo, the city’s first African American police chief, could change the culture of a department that critics said too frequently used excessive force and discriminated against people of color. He spoke of restoring trust during a swearing-in ceremony that became a community celebration featuring song, dance and prayer in a center close to where he grew up.

But George Floyd’s death, which ignited nationwide protests over racial injustice and police brutality, has raised questions about whether Arradondo — or any chief — can fix the department now facing a civil rights investigation.

Steve Belton, president and CEO of the Urban League of the Twin Cities, said Arradondo inherited a department with a history of misconduct “over many, many, many decades” and “it won’t be fixed overnight, maybe not even in this particular moment or with this particular chief. Change takes time.”

Arradondo, a fifth-generation Minnesotan, joined the Minneapolis Police Department in 1989 as a patrol officer, eventually working his way up to precinct inspector and head of the Internal Affairs Unit, which investigates officer misconduct allegations. Along the way, he and four other black officers successfully sued the department for discrimination in promotions, pay and discipline. His predecessor, Janee Harteau, promoted him to assistant chief in early 2017.

He took over months later, after Harteau was forced out over the fatal shooting of Australia native Justine Ruszczyk Damond, who had called 911 to report a possible sexual assault behind her house. The black officer in that case was convicted of third-degree murder and is serving a 12 1/2-year term. Damond’s death came two years after 24-year-old Jamar Clark, who was black, was killed in a scuffle with two white police officers, setting off weeks of protests; neither officer was charged.

Arradondo made some quick changes, including toughening the department’s policy on use of body cameras. But City Council member Steve Fletcher said Arradondo was lenient with discipline in his first year as chief as he worked to build department morale, which made getting rid of problem officers difficult later.

“I think the chief’s heart is in the right place,” Fletcher said. “But I don’t think this department was ever going to let him get there.”

“I think people understand he was in an impossible situation,” Fletcher added.

Police spokesman John Elder said Arradondo has succeeded with some changes. For example, all officers — new and tenured — must go through training that stresses respectful interaction with the public. Elder said the chief was immersed in Floyd’s memorial service Thursday and was unavailable for an interview.

Arradondo quickly fired the four officers at the scene of Floyd’s death.

Derek Chauvin, the white officer seen on cellphone video pressing his knee into Floyd’s neck while ignoring pleas that he couldn’t breathe, has been charged with second-degree murder and other counts. City records show he had 17 complaints against him, only one of which resulted in discipline. He also shot two people during his 19-year career and was never charged.

The other three officers were charged with aiding and abetting second-degree murder.

Harteau said she received push-back from the union when she was trying to implement reforms. This week she called on police union President Lt. Bob Kroll to resign after he called the unrest in the city “a terrorist movement” and suggested police should have been able to use tear gas and more forceful measures early on.

Kroll — who praised Arradondo when he was promoted to chief — said the city is anti-police and withheld needed resources and manpower. He did not immediately return messages from The Associated Press seeking comment.