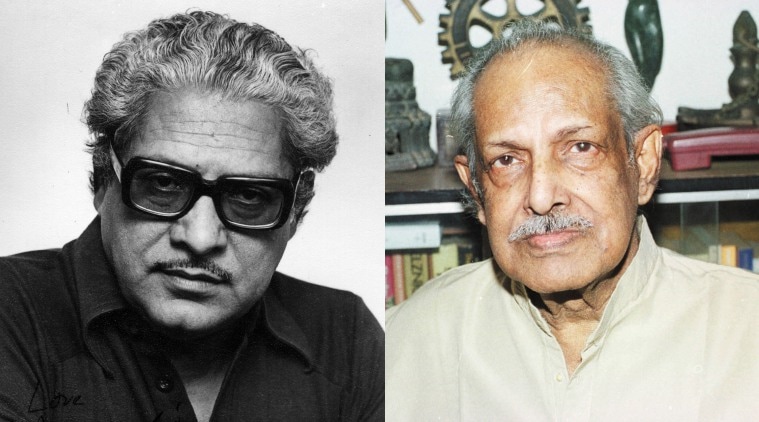

Basu Chatterjee had comfortably settled into making films that had all the essential ingredients of Hrishikesh Mukherjee films. (Express Archive Photo)

Basu Chatterjee had comfortably settled into making films that had all the essential ingredients of Hrishikesh Mukherjee films. (Express Archive Photo)

My earliest memory of Basu Chatterjee is of one of his lesser-known (and celebrated) films. It also involves one of the greatest injustice meted out to him, attributing his film to another Bengali stalwart, Hrishikesh Mukherjee. 1978’s Dillagi, starring Dharmendra and Hema Malini, was definitely not one of his best films, neither was it a huge success, but it became a family favourite simply because we managed to acquire a video cassette of it sometime in the early 1990s. As any 1990s kid will tell you, video cassettes, like tape cassettes, are meant for repeat viewing until it unspools in your cassette player (even then there are ways of fixing it). Dillagi, a breezy romantic comedy about a nerdy chemistry lecturer (Hema Malini) falling for an equally nerdy Sanskrit professor of a girl’s college, has all the ingredients of the middle-of-the-road cinema that made Hrishikesh Mukherjee a household name in the 1970s and 1980s. The characters were distinctly middle-class, the conflicts didn’t involve scheming villains and hungry crocodiles and the idiom almost relentlessly commonplace.

No wonder I mistook it for a Hrishikesh Mukherjee film. I didn’t know better. Not until college, when I tried to convince a Hrishikesh Mukherjee fan that there was a film of his favourite filmmaker that he didn’t know about. He didn’t budge from his stand. Hrishikesh Mukherjee has never made a film called Dillagi.

This was the early 2000s. Wikipedia was still not a thing. Perplexed, I watched the film again. Of course, the title sequence told me it’s a Basu Chatterjee film, but there were also other giveaways. As a Bengali, I was embarrassed, of course. How North-Indian of me to club the Mukherjees and the Chatterjees together, but I was also sobered as a self-proclaimed Bollywood-phile. How could I not see the subtle yet undeniable distinctions between these two universes.

The similarities

Basu Chatterjee, who can easily be called one of the pioneers of the parallel cinema movement of the 1970s, made his debut in 1969 with the stark and beautiful, Sara Aakash. Hrishikesh Mukherjee was a part of legendary filmmaker Bimal Roy’s core group that travelled from Kolkata to Mumbai in the early 1950s.

Both these filmmakers turned to the wealth of Bengali literature several times in their respective careers, something that endeared them to the Bengali audience and also ensured that their films dealt with themes of progressive socialism. Chatterjee revisited Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay time and again in films like Swami (1977) and Apne Paraye (1980). As did Mukherjee in films like Majhli Didi (1967). Yet, even in the adaptation, we see Chatterjee gravitating towards the inner worlds of his female protagonists. Mukherjee too touched upon similar topics in earlier films like Anuradha and Anupama, but not with similar consistency. Eventually, when Mukherjee started making films that went on to become a self-defining genre, the quintessential Hrishikesh Mukherjee films like Guddi (1971), Anand (1971), Chupke Chupke (1975), Gol Maal (1979), Chatterjee had comfortably settled into making films that had all the essential ingredients of Hrishikesh Mukherjee films, but were outliers nonetheless.

Basu Chatterjee passed away on Thursday in Mumbai (Photo: Express archive).

Basu Chatterjee passed away on Thursday in Mumbai (Photo: Express archive).

A distinctly feminist voice

I choose the word outlier because a Basu Chatterjee film, would often be dressed in similar garbs, but they were of different ilk (as they should be). It will be hard to mistake Chatterjee’s Rajanigandha (1974) as a Hrishikesh Mukherjee film, though it has all the makings of one. A mellow exploration of the female psyche, Rajanigandha is almost Jane Austen-like in its quietude. It talks about Deepa (Vidya Sinha) and the way she considers two men in her life, Sanjay (Amol Palekar) and Naveen (Dinesh Thakur). She is not torn between the two, not affronted by some deep-rooted moral dilemma when it comes to choosing between two possible suitors. She is rather governed by fortitude. She chooses the whimsical Sanjay over the more dependable Naveen probably because she feels she can make a difference in his life; we are not privy to that. However, in 110 minutes that we spend with Deepa, we never judge her. She is never compelled to feel bad about anything. She is never deprived of her agency to make decisions. This at a time when Bollywood told you that women are love objects to be ferried about by two sacrificing friends. Case in point, Aap Ki Kasam that released the same year.

In the film that introduced me to the Basu Chatterjee world, Dillagi, women are sexually assertive and ambitious, and they are never made to feel apologetic about it. Phoolrenu (Hema Malini), who is an independent woman supporting her family, is somewhat prudish when it comes to sexual expression. Her character is in direct contrast to her friend and colleague Geeta (Mithu Mukherjee), who makes no bones about her relationship with Shekhar (Shatrughan Sinha). These women are not made to judge each other, instead, there is some gentle chiding and rebuking when they overstep lines. Chatterjee ensures that Phoolrenu realises that sexual expression isn’t really a moral issue at all.

In the much-loved Chameli Ki Shaadi (1986), Amrita Singh gets a career-best role as a decisive young woman who is in love with a man from a different caste (Anil Kapoor). She overcomes parental opposition with dogged determination to marry the man she desires.

Eventually, in the 1980s, both these filmmakers made films that were thematically very alike. Chatterjee’s Humari Bahu Alka (1982) and Mukherjee’s Kisi Se Na Kehna (1983) both tried to expose the oppressive nature of patriarchy comically. The patriarch in both these films was portrayed by Utpal Dutt. Yet, the distinctly different approach of both these filmmakers is evident even in these lesser films. While Humari Bahu Alka sidesteps the burden of being a morality tale, Mukherjee’s Kisi Se Na Kehna ensures that the audience walks away with a moral lesson or two.