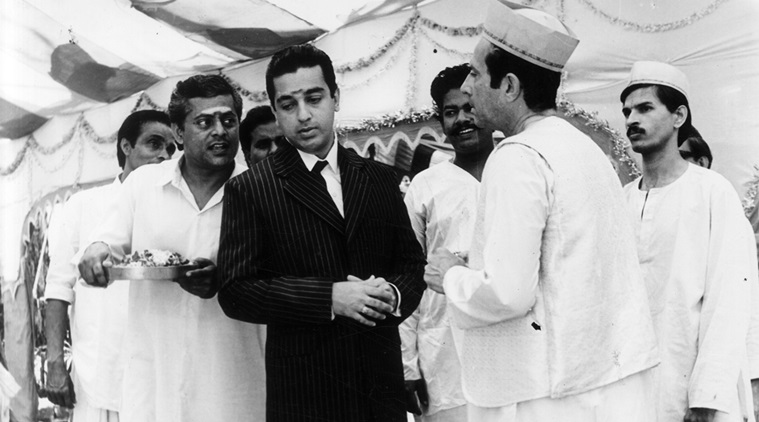

A thinly-veiled autobiography of Mumbai’s famous don Varadarajan Mudaliar, Kamal Haasan-starrer Nayakan follows the rise and fall of Velu Naicker. (Express archive photo)

A thinly-veiled autobiography of Mumbai’s famous don Varadarajan Mudaliar, Kamal Haasan-starrer Nayakan follows the rise and fall of Velu Naicker. (Express archive photo)

1987 was a watershed year, at least for an eight-year-old me. On one extreme end was Shekhar Kapur’s Mr India which blew my mind at that age and on the other, Mani Ratnam’s Nayakan. Not so much a theatrical experience as a VHS one, I watched the Mani Ratnam masterpiece over two-three different Tamil prints which had, as usual, bad sound and bad visuals. But on the first viewing itself, I don’t know, but something happened. In my house, a lot of Tamil films were played on VHS, but most of them bootlegged, none of them originals. My memory of cinema is very bootlegged, in that sense. Starring Kamal Haasan, Saranya and Karthika, Nayakan was a similar experience. I could hear murmurs and family chatter from behind complaining that they couldn’t see anything, the camera work being too dark but that didn’t bother me because I hadn’t seen visuals like these before. Kamal Haasan, for the first time, was clean shaven. He looked really different. For Nayakan, his hairstyle was different, he had taken off the moustache and right in the beginning, it’s about this kid who gives away his father and the father gets killed because of that. Such a powerful opening that it shakes you up. You follow this boy (Kamal Haasan as Velu Naicker) who grows up to become a dreaded gangster from one point of view and a messiah from another. Since I was young, I couldn’t pigeonhole these films into classical structures. I saw Nayakan before The Godfather. So, Nayakan had a bigger impact. I had no reference point to it. Also, by then, Varadarajan Mudaliar, or Vardha Bhai as he was widely known, was a big name in Matunga where I grew up. Being from the same neighbourhood, my parents had heard his name from his bootlegging days. Varadarajan Mudaliar’s Ganesh pandal near the Matunga station was so famous that a strong legend had already built around it and when you are watching Nayakan with Kamal Haasan playing a version of Vardha Bhai, you know what you are getting into. I wasn’t allowed to read Tamil magazines, but I could hear all the conversations when the film was being played. When you are a kid, you are in charge of taking the VHS, putting it in, cleaning the head with the spray, putting the connections and seeing the volume and things like that and as you are doing it, there are these murmurs that go on around the film, and that is when you catch all the trivia or you understand what this film could be. So, this is how every film was introduced at home, and this is how Nayakan was also introduced — through a bad print but with a lot of excitement and noise.

The film is about Velu Naicker’s rise as an underworld figure in Bombay’s Dharavi. Mani Ratnam charts an inter-generational journey, from Velu’s days as a young migrant through his old age. What Mani Sir did at the time was to domesticate or humanise a gangster, by showing his family life and relationships. So, Nayakan has a lunch scene, friendships, touching family moments like a father putting his son to sleep, there’s a mosquito net and nice lighting, so you almost forget that his wife Neela (Saranya) was a prostitute and he’s a gangster. Mani Sir normalises their lives. He takes away the stigma, so it’s like watching just another family at home. We hadn’t experienced this before, because a wise-guy usually dressed a certain way or spoke a certain way. In Satya (1998), Ram Gopal Varma introduces Bhiku Mhatre (Manoj Bajpayee) as a normal, family guy. When we first see him, it’s not a shot of him killing anyone. There’s no blood or a fire shot, but he’s simply talking on the phone, and his wife (Shefali Shah) puts a hot cup of tea on his shoulder. The kids are saying things like they don’t like bread and omelette. Basically, small household stuff like what people eat, harmless niceties like ‘Will you have water or tea?’ etc., I think these conversations sneaked into a gangster film to make it more relatable.

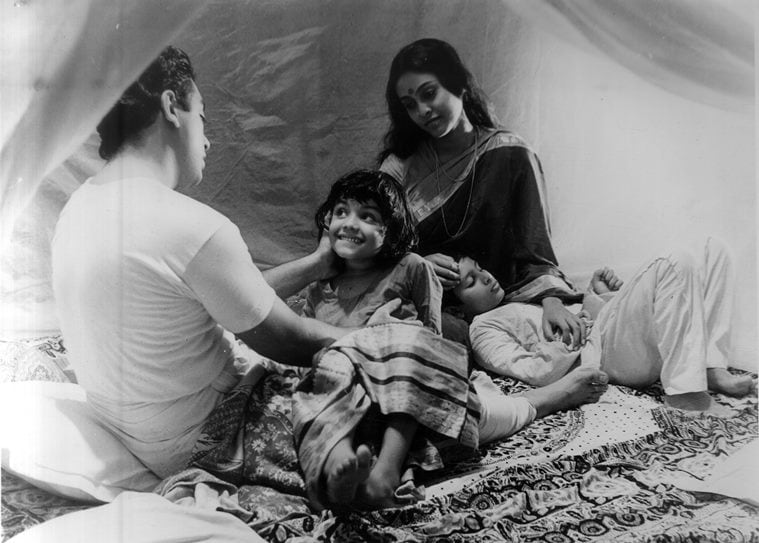

In Nayakan, Mani Ratnam humanised a gangster, by showing his family life and relationships. (Express archive photo)

In Nayakan, Mani Ratnam humanised a gangster, by showing his family life and relationships. (Express archive photo)

Standing for equality

Velu Naicker is a man who believes in relationships. Look at his bond with the mentally challenged Ajit (played by Tinnu Anand). He’s not just loving him but doing so because he’s filled with guilt as Velu has killed his father. But the circle of violence closes at some point, and Velu gets his comeuppance. He gets killed in the end by the inspector whose father was killed by Velu. Velu keeps Ajit as a bodyguard. It’s a tender gesture in the sense that as a young boy Velu was once bullied, and he doesn’t want Ajit to go through the same. So, he keeps the weaker guy closer and gives him a false sense of authority to live his life with pride. These touches are so brilliant. This is a film where the marginalised, if I may put them that way, are given a dignity that’s denied to them, be it with Ajit, or the prostitute who’s given legitimacy when she marries a powerful don and becomes a housewife. Mani Sir keeps pushing this feeling throughout the film, that humans need dignity and people should be treated equally. Like the scene with the doctor neglecting a poorer patient. Velu steps in and makes sure that the poor man’s life is as important as any other. In the 1980s, the class divide was huge. The education was public, globalisation hadn’t happened, and economic opportunities were still decades away. At a time like this, Velu pushing that whole talk of equality at every level was so empowering.

Watch Kamal Haasan’s performance and see how detailed and nuanced it is. For someone who has acted in 300 films, making a list of Kamal’s top 10 performances is not an easy task. He’s a powerhouse of Tamil cinema. Just a year prior to Nayakan, we had seen him in K Balachander’s Punnagai Mannan. The film is about a couple who decide to commit suicide. The girl dies but the man survives, and he’s overridden with survivor’s guilt, and then he falls in love with a Sinhalese woman at the height of the LTTE movement. A Tamilian falling in love with a Sinhalese was taboo, but Kamal never shied away from pushing boundaries. There was also Moondram Pirai (or Sadma in Hindi), Salangai Oli, which explores his passion for classical dance, and Sahtya. Yet, Nayakan remains one of his most unforgettable performances. It starts with the first time we see his face as a young man. Now that we are talking about it I realise it’s the same shot with Bhiku Mhatre in Satya, looking behind. The first thing I noticed was Kamal Haasan’s ageing don. Usually, when Sivaji Ganesan ages it’s the exaggerated wig and greying of hair with a little bit of slouching, but essentially, the face is the same, as eternally young as ever. But what Kamal did was unimaginable. He added real weight. He got fully into the character. People didn’t do these things specifically for a film those days. This was much before Daniel Day-Lewis or Aamir Khan. There was a norm of working multiple shifts a day, churning out six-seven hits a year and Kamal was taking away all that time just to shoot this one film? Incredible! But the effects are there for you to see. Because when you watch him age and wisen up gradually at every Ganesh Chaturthi, you see the old man really look like an old man. Not just the way he talks and moves but even the way he behaves with people. Manoj Bajpayee had done something similar in a Gangs of Wasseypur (2012) scene where Danish (Vineet Kumar) is getting married and Manoj has to stand up and dance at a function and the way he dances off-rhythm was a riot. It reminds you of the way Velu moves and just humours Ajit in Nayakan. Probably, Manoj must have taken a leaf from there. When actors do certain things to put in that extra bit of authenticity when movies don’t have the budget or resources for that kind of makeup detail, it’s a blessing for filmmakers. The actor really needs to step up and come up with these nuances to keep grounding the fact that, ‘Oh, so much time has passed.’ In the second half of Nayakan, Velu has aged. He’s not the hot-blooded young guy anymore and has reached the position of power. You can see that he’s doing things differently than he’d have done as a young man. Kamal gets all these aspects right, and it is a lesson for all actors.

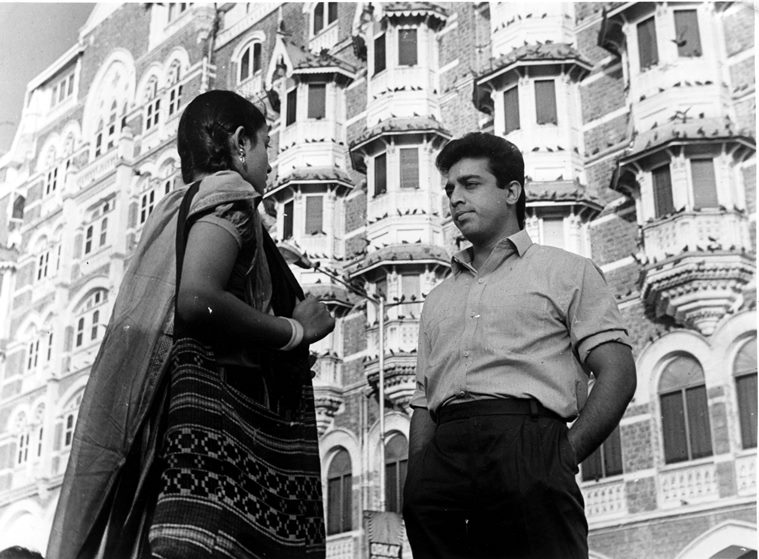

Kamal Hassan in a still from Nayakan. (Express archive photo)

Kamal Hassan in a still from Nayakan. (Express archive photo)

Kamal versus Rajini

There are some similarities between Nayakan and Sadma, especially Kamal’s coming-of-age from boyhood to manhood. In both films, it is his friend who takes him to an escort, but he’s also ready for the experience and once he gets into the door then his perspective on life changes. In Sadma it is a child-woman (Sridevi) he meets and in Nayakan, it is a schoolgirl forced into prostitution. So, it’s interesting the kind of roles he has picked and the boundaries he has chased. 1980s’ Tamil cinema was all about a macho hero and a girl chasing him and falling at his feet and what followed was the archetypical taming of the shrew where the macho hero has to tame the outrageous, rich spoilt brat. It’s not like Kamal has not done that, but he’s also constantly challenged himself.

Rajinikanth has also played gangster, most recently in Kaala and Kabali. Mani Sir followed up Nayakan with Thalapthi (1991), a slicker revisiting of some of the same themes — this time with Rajini. Both Rajini and Kamal had become superstars in the ’80s in different ways. Rajini was more popular, but Kamal was no less, and it was hotly debated among cousins as to who was the best. Honestly, I grew up as a Kamal fan and only later shifted allegiance to God Rajini. I don’t know why that happened. Somehow, in my innocent years, I was chasing complexities, but after having grown up, I wanted that very innocent, broad-stroke hero to look up to. The switch happened later. Ideally, I should’ve been a Rajini fan and then become a Kamal fan, but it was the opposite. Now, coming to Rajini’s gangsters. Rajini always pitched him as larger than life. Whatever Thalaivar does leads to mass hysteria, and you rarely see the human behind the superhero. But with Kamal Haasan, he doesn’t realise that he has that power. A scene in Nayakan shows him paying for his cup of tea. He’s flummoxed as to why people aren’t accepting money from him. His friend says it’s going to be this way from now on and he’s not sure whether to accept that role yet. He’s doubting if he’s even worthy of this adulation. But if Rajini were to play this, he would feel he was born into it. There are no two ways about that, because Rajini comes from a very different imagery. He’s dark-skinned and not conventionally good-looking. So, to assert heroism, you need to go a couple of notches higher whereas a handsome guy like Kamal doesn’t have to assert that. The audience is attracted to him, regardless. Kamal has to just sit and people flock. He’s eye-candy, but the added bonus is that he’s a creative genius, a great actor, a thinker and cinephile. But that doesn’t mean he can’t be populist. They say, in cinema or literature, it is the EQ that trumps the IQ. Emotional quotient makes you more popular than your IQ and anyone who chases IQ won’t have that kind of mass following. Rajini was smart enough from the beginning to keep the EQ blasting at blaring levels. In reality, he’s a sharp guy, and it takes a sharp guy to understand how it works in the movies.

Mani Ratnam’s lasting influence

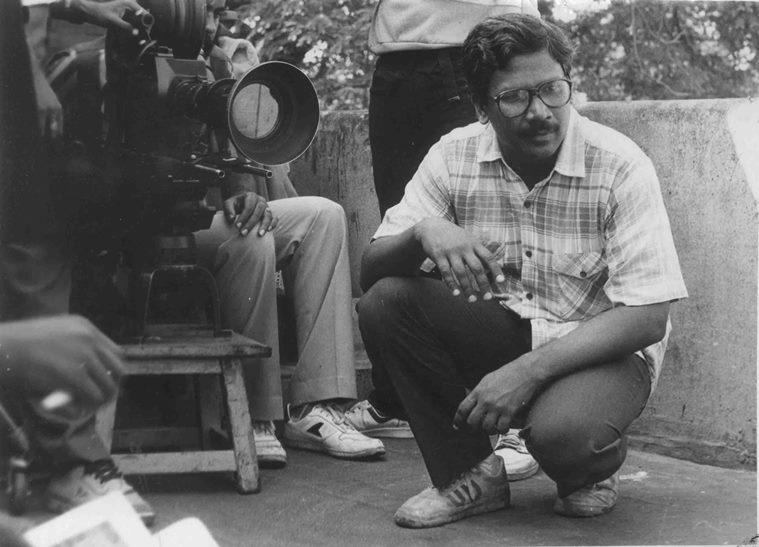

Mani Ratnam on the sets of Nayakan. (Express archive photo)

Mani Ratnam on the sets of Nayakan. (Express archive photo)

In Nayakan, Mani Ratnam and Kamal Haasan make for a dream team and of course, Ilaiyaraaja whose theme music still gives me goosebumps. The film hits you when you are least prepared. It’s not like one of those arthouse films. What separates Mani Sir from other filmmakers is his talent to find artistic potential even within the so-called mainstream framework. For instance, in a serious film like Nayakan, he manages to insert a seductive and provocative item number on the boat and so well sung by Ilaiyaraaja. But there’s nothing vulgar about it. It’s funny that the sidekick has got entertainment on the boat. Also, it flows so beautifully into the screenplay. It’s another matter that all this entertainment fails to break Velu’s focussed mindset. He is tying salt bags on to the bootlegged alcohol and putting them into the sea. Once it goes undetected by the navy and the salt dissolves, his things come up. You see Mani Sir’s brain at work here. Mani Sir’s genius is that he creates a great song and at the same time, never allows the plot to compromise. Overall, the film highlights Mani Sir’s commitment to intensity and reality as well as making it all within a commercial genre. The people he casts in his films look like they belong to their places. There’s something ordinary about them, yet something attractive.

My introduction to Mani Sir happened through Mouna Ragam (1986), and then I saw Pallavi Anu Pallavi (1983), Unaru (1984), Anjali (1990) and Iruvar (1997). Revathi was a huge star, and if you were from the Matunga-Chembur belt, then you were a devout Revathi fan. Nobody can beat Mani Sir in romance and relationship. But when he brings suggestions of violence, it can scare and scar you. Like in Nayakan, when the boy sprinkles blood on Velu’s face, or the coconut scene in Roja. In Dil Se, you can feel the violence and the disruption that has happened and the messiness in that lockjaw scene featuring Manisha Koirala. That’s scarier than any violence, as it triggers her character’s childhood memories. I still get the creeps thinking of that scene and the helplessness that Mani Sir showcases. Though a crime drama Nayakan also highlights Mani Sir’s mastery over relationships. I feel if you have to make a gangster film in today’s time, then you have got to have a special point of view, which Mani Sir had in Nayakan. I must confess at this point that Mani Ratnam is the reason why I am a filmmaker. The first thing I did after I told my parents that I want to be a filmmaker was to go to Madras and stand outside Madras Talkies to try and gain access to Mani Sir. I couldn’t. So I came back and fortunately met Anurag Kashyap.

Is gangster genre dead?

Besides Nayakan, two of the most influential early gangster films from Hindi cinema are Vidhu Vinod Chopra’s Parinda (1989) and Sudhir Mishra’s Is Raat Ki Subah Nahin (1996). Even Ashish Vidyarthi’s character in Is Raat Ki Subah Nahin has gone through a cycle of violence. Lately, Gangs of Wasseypur (2012) and Kammatti Paadam (2016) were top-notch. Though Nawazuddin Siddiqui’s character in Gangs of Wasseypur II was highly celebrated, Manoj Bajpayee as Sardar Khan was something else. His act is right up there with all the great performances. Irrfan Khan in Maqbool (2003) was also first-rate. I have this theory that a performance is sublime when an actor uses minimum tools. Irrfan aces it for me. His tools aren’t visible, and you don’t know what he’s clutching on to for characterisation. Then, there’s director Rajeev Ravi who gets the genre very well, and he knows how to shoot it stylishly, too. His stories are deeply rooted in Kerala, and that’s why Kammatti Paadam worked for me. Even Vaastav (1999) is worth mentioning. Though it didn’t have the slickness of Nayakan or Satya, it did have a lot of truth and heart. Mahesh Manjrekar is from here and he understands the Marathi milieu. Raghu’s (Sanjay Dutt) marginalisation, class divide and hurt pride come across in an organic way. Everyone has faced it or seen it first-hand, and that first-hand information translates into Vaastav. Then, there was Bombay Velvet, where we missed the mark, but Sacred Games worked out beautifully. That’s because it cuts into the past. I don’t know what a present-day gangster film will look like.

The fact remains that the way mafia affected Bombay it didn’t affect any other part of India. Which is why gangster films are a Bombay/Mumbai thing. Those who came of age in the 1980s-90s will remember what a menace the underworld had become. At one point, it was a parallel government or economy that was running the state. Today, the gangster genre is probably dead. You might have galli ka gundas these days, but you don’t have flamboyant bhais who once ruled the city. They’ve been wiped off and the power has shifted to other people. We are dealing with larger and bigger problems like terrorism. Does anyone today even remember dons like Varadarajan Mudaliar or Haji Mastan? They were big in their time but irrelevant today because we don’t need to smuggle things anymore. Everything is available on Amazon. Globalisation killed the need for it. The class divide is blurring. The cart-puller’s son from the 1980s is a bank employee of 2020. You know everyone has risen in their class. That shift has changed everything, and there’s no place for the gangster in Mumbai of today.

(Vasan Bala is the director of 2018’s acclaimed pastiche, Mard Ko Dard Nahi Hota. He spoke to Shaikh Ayaz)