The impact of the COVID-19 crisis has been so acute that it has left the government with little choice but to consider measures often regarded as relics of the past

The break-up of the Rs 20 lakh crore fiscal stimulus has generated a lot of discussion. While reviewing the various policy measures, I was taken back to an earlier era -- the post bank nationalization period of the 1970s. Measures such as credit guarantees, interest subvention, Viability Gap Funding, support for MSME (Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises) and agriculture etc. remind one of those days.

The impact of the COVID-19 crisis has been so acute that it has left the government with little choice but to consider measures often regarded as relics of the past. We will discuss credit guarantees (CG) in this piece, tracking its history from the 1960s to its most recent avatar.

Idea of Credit GuaranteeThe Indian government first started giving credit guarantees to the Small Scale Industry (SSI) in 1960. The guarantee fee was levied at 0.25 percent of the guarantee amount, which was deemed high by industrialists. The RBI’s Industrial Finance Department administered the scheme.

In the late 1960s, discussions picked up over making banks more socially responsible by asking them to give loans or open branches in neglected sectors/areas. It is interesting to note that the then RBI Governor PC Bhattacharya preferred credit guarantees over Social Control of banks. His view was that a decentralised CG for SSI loans given by the banking system “can play a much larger role than at present in the field of financing small industries”.

The credit guarantee idea gained momentum post bank nationalization. In a meeting with nationalised banks in September 1969, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi said there was a need for "a simple but wide-ranging scheme of guarantees or comparable facilities for lending by banks in fields which have remained relatively neglected so far, such as retail trade, small business, minor repair industries, small farming and the self-employed sector".

Road to Credit Guarantee CorporationThe government formed a working group comprising custodians of the nationalised banks. In its report, the group said while the objective of giving loans to neglected areas was noteworthy, it will also lead to risks for the banking system. The best way would be to pool these risks and cover them under a common guarantee scheme. To avoid moral hazard, guarantees would be capped at 75 percent of the losses so that banks do proper loan appraisal. The guarantee fee was pegged at 0.25 percent of the loans, open to review. Interestingly, the government credit guarantee scheme had a fee of 0.1 percent for SSIs.

The group proposed that the Deposit Insurance Corporation take up the function of credit guarantee as well. This was because the purpose of deposit insurance (DI) and CG is the same: to protect banks and their depositors. However, the government wanted a separate organisation, leading to the establishment of the Credit Guarantee Corporation (CGC). The report suggested that all credit guarantees be brought under this one umbrella, but this was again deferred.

The CGC was registered under the Companies Act (1956) on January 14, 1971, and commenced business on January 29. The company was promoted by the RBI and 71 scheduled banks contributed to its share capital. The Board had 6 members, two represented RBI and four were from commercial banks. The first chairperson was R K Hazari, RBI Deputy Governor.

The CGC launched three schemes in 1971 itself. The Credit Guarantee Corporation of India (Small Loans) Guarantee Scheme, 1971, covered credit extended by scheduled commercial banks to the priority sector, barring the small scale industry and including famers and agriculturists, transport operators, fertilizer dealers, traders, professional and self-employed persons etc. The second scheme, named the Credit Guarantee Corporation of India Small Loans (Financial Corporations) was for state finance corporations which in turn gave credit to similar types of business as enumerated in the first scheme. The third scheme, called the Credit Guarantee Corporation of India (Service Cooperative Societies) covered select cooperatives.

Merger of CGC with DICGC

The CGs led to not just an increase in credit towards these neglected areas, but also of rising claims. The CGC expedited the processing of claims, but that also weakened its financial position. This weak financial position led to the merger of the CGCI with the DIC to become the Deposit Insurance and Credit Guarantee Corporation. The group which led to the formation of the CGC had anyway recommended the DIC to take over the tasks of credit guarantees. So, it was more like coming home really. The Act to provide for acquisition of the CGC by the DIC was passed in April 1978 and came into effect from July 15, 1978.

The DICGC came to be fully owned by the RBI and the board strength was raised to nine. The Act provided for either the RBI Governor or the Deputy Governor (DG) heading the board, but tradition led to one of the DGs chairing the board. The integration of the two also allowed funds to be transferred from one arm to another in case of a financial problem. Indeed, in 1978, the CG fund had to be bailed out by the DI fund as the former had more claims to settle compared to the collected fee income. The claims had partly gone up as the guarantee cover had increased from 75 percent to 90 percent, which also led to a rise in moral hazard.

In 1981, the Government’s small industry scheme was transferred to DICGC and its fee was increased to 0.25 percent in line with that of DICGC’s schemes. RBI also increased the capital of DICGC to Rs 15 crore. In 1984, DICGC introduced another scheme providing guarantee cover to select primary agricultural credit societies (PACS), primary land development banks (PLDBs) and branches of state land development banks (SLDBs), for their loans to agriculture and allied sectors.

1991 reforms and decline of Credit Guarantees

In 1992, of the six CGs, three were stopped: Small Loans (Financial Corporations) Guarantee Schemes, 1971, Service Co-operative Societies Guarantee Scheme, 1971 and Small Loans (Co-operative Credit Societies) Guarantee Scheme, 1982.

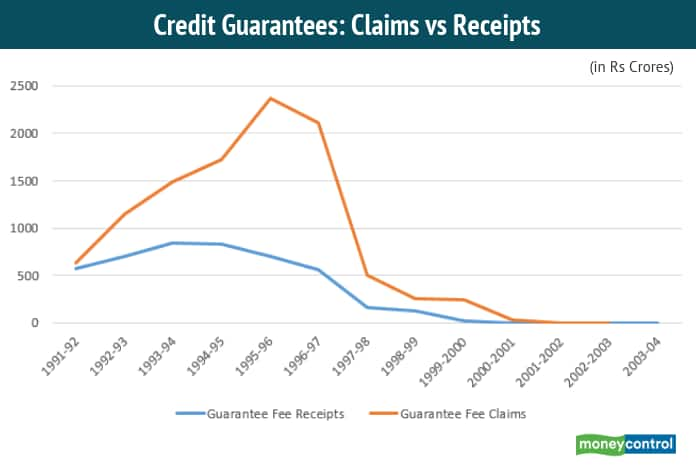

Post-1992, fewer banks used the CG scheme. This was partly because of the more stringent norms adopted by the DICGC for invoking the guarantees. It was also partly because of the 1991 reforms, where banks were moving to more market-determined ways which required doing away with the earlier approach of guarantees. The claims were more than receipts for most of the 1990s and then gradually both declined to zero.

By 2003, no bank was participating in the CG schemes barring one cooperative bank. The DICGC closed its CG function in April 2003 and became responsible for only deposit insurance.

The Government had already noted the decline of CGs. In his 2002-03 Budget Speech, FM Yashwant Sinha had proposed to convert DICGC into a Bank Deposits Insurance Corporation (BDIC) “to make it an effective instrument for dealing with depositors’ risks and for dealing with distressed banks”. A team from RBI and the Finance Ministry had studied and visited the US Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). The team prepared an outline of the Bank Deposit Insurance Corporation (BDIC) Bill, 2003 and submitted it to the Finance Ministry in February 2003.

The Ministry had commented that BDIC should have authority to initiate remedial measures for failing banks if the regulatory/ supervisory authorities do not act promptly. Further, it recommended that a senior RBI official should be on the Board to facilitate information sharing on regulation and supervision. The RBI Governor had also opined that DICGC should work on a new law that suits India’s financial conditions while taking into account the latest international best practices.

By 2003, the earlier combination of Deposit Insurance and Credit guarantees had become anachronistic and the new combination was a deposit insurance and resolution regime. Both Deposit insurance (see my piece on history of deposit insurance) and the lack of a bank resolution regime have been in the news of late due to large scale banking failures. The events have prompted the government to increase the deposit insurance limit to Rs 5 lakh from Rs 1 lakh.

However, it is not clear why we do not have a bank resolution regime, despite starting the discussion way back in 2002. In 2017, the Government proposed the Financial Resolution and Deposit Insurance Bill but it ran into controversy over its approach to resolution.

CGs today and Final Thoughts

The credit guarantees did not die completely. In 2000, the government and SIDBI established a Credit Guarantee Fund Trust Scheme for Micro and Small Enterprises (CGTSME). In 2014, the government started several CG funds (Skill Development, Standup India, Factoring etc) and then set up a National Credit Guarantee Trustee Company Ltd to coordinate these funds.

In the Rs 20 lakh crore fiscal stimulus announced by the government, there is a credit line to MSMEs worth Rs 3 lakh crore which is going to be 100 percent backed by CG and covers both interest and principal. Additionally, the government plans to provide Rs 20,000 crore of subordinate debt to MSME promoters which could be used as equity. The government will provide Rs 4000 crore to CGTSME which in turn will provide partial credit guarantee to banks under this scheme. The other schemes provide full and partial guarantees to NBFCs, HFCs and MFIs to enable them to raise liquidity and capital. Thus, we are back to not just CGs but the possibility of multiple CGs being governed by multiple agencies.

The history of CG and its functioning does give us some lessons. First, we should avoid multiple agencies handling different CGs. Second, the RBI or RBI-governed institutions generally fare better at financial tasks compared to the government and its agencies. The government should closely work with the RBI and heed its advice on not just CGs but other aspects of the fiscal stimulus as well, which relies greatly on the banking system. Third, we should be careful of moral hazard problems. This does not imply that one should not lend, fearing moral hazard. It is just that CG should not result in loan appraisals and follow-up not being done properly. Indian banking is already struggling with high NPAs and banks should take care to avoid any further rise.

Amol Agrawal is faculty at Ahmedabad University. Views are personal.