Dharavi accounts for nearly 3% of Maharashtra’s Covid-19 patients, and more than 4.5% of Mumbai’s cases

Dharavi accounts for nearly 3% of Maharashtra’s Covid-19 patients, and more than 4.5% of Mumbai’s cases

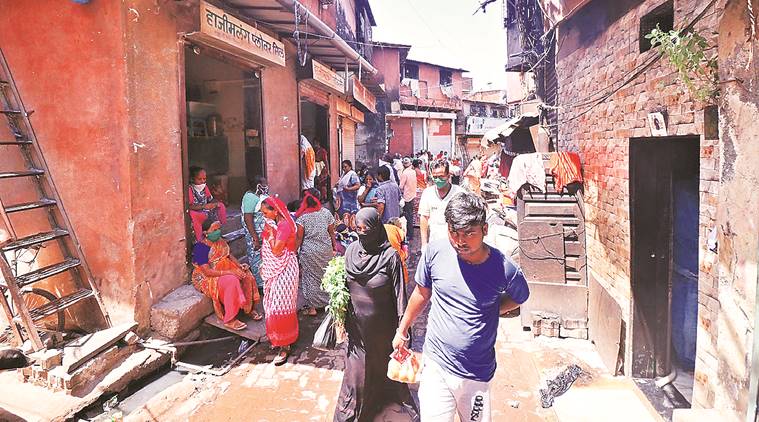

AFURTIVENESS cloaks Dharavi now, its departing inhabitants wary about stating their local address. This is a far cry from last decade’s celebration of Dharavi’s industry and enterprise, the slum’s casting as the beating, clanging, whirring heart of Mumbai’s famed pursuit of overcoming the odds.

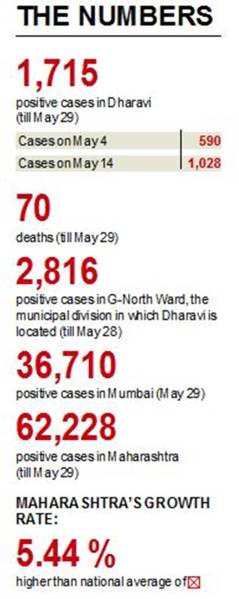

At 1,715 Covid-19 cases until Friday afternoon, the 2.4-sq-km slum sprawl accounts for nearly 3% of Maharashtra’s patients, more than 4.5% of Mumbai’s cases, and more positive cases than in all of Odisha or Kerala.

The municipal division that Dharavi belongs to, the G-North Ward, has the most cases among Mumbai’s 24 wards, and more than 60 per cent of these patients live in Dharavi.

But inside the slum, in the dark alleyways where upper floor overhangs and monsoon tarps and tangled cables provide a dank shade from a blazing May afternoon, the conversations are not about the disease at all, nor about the neighbourhood cases or quarantined families.

“When can we go back to work?” asks Shaheen Shaikh, 45, waiting outside a municipal health post for a painkiller after pulling a back muscle. Her husband is a severe alcoholic, sinking all his wages into his fix on the days that he managed to haul himself to a nearby traffic junction to be picked up by labour contractors. Shaheen has raised her six children by making bead trinkets at home. The older children have dropped out of school now, and her eldest son, just 18, lost a two-month-old job as a store helper at the start of the lockdown. “There are limits to charity also. Everyone in Dharavi will tell you that the groceries being handed out by charitable organisations are gradually shrinking,” she says.

The growth curve link

with 1,715 Covid-19 cases among less than a million people, Dharavi in Mumbai is India’s largest contiguous hotspot. With every third Covid-19 patient in India now in Maharashtra, the curve for the national growth rate very closely resembles that of the state — if the spread in Maharashtra is contained, or its growth slowed down, a sizeable part of the problem in the country would be taken care of

Shaheen’s dupatta is wound around her head and covers much of her face. The other patients waiting patiently at the health post all wear face masks too. The attendant writing down patient details sits behind a desk and wears a partial PPE, the auxiliary nurse midwife (ANM) wears a face mask and gloves. But the patients sit right next to one another, inching closer together as conversations begin, not about the pandemic but about health facilities in the teeming slum.

Bugappa, an Andhra Pradesh native who has worked in Mumbai as a construction worker for more than two decades, has brought his daughter to the clinic with a severe chest congestion. “It doesn’t make any sense to go to the private clinics. They charge a pretty fee to eventually send us back to municipal hospitals. But at the municipal clinic, we get the same medicine at every visit — no change in medication even if the patient hasn’t improved,” he says.

Eight years old, Aarti Bugappa declares between coughs that she has quit school after Class II, quite firm even when her weary father tells her she’s expected to return when schools re-open. Her schooling is one of the reasons Bugappa is toughing it out through the lockdown, the other being that there is no landlord breathing down his neck — he owns the pucca slum structure where he lives.

Waiting with them is Premchand Patwa, who is given a loud dressing down by the ANM for not visiting the nearby Lokmanya Tilak Municipal General Hospital to show doctors the lump growing in his abdomen.

“Will markets be normal before Rakshabandhan?” is all he wants to know, waving off concerned queries about whether the lump is painful. Patwa makes colourful rakhis at home, and survives the rest of the year doing odd jobs. “Everything else is just fine,” the Allahabad native assures you, taking off his face mask to have a conversation.

***

By various estimates, 8.5 lakh to a million people live in Dharavi, rendering the slum’s incidence of Covid cases per million nearly 13 times the per million rate for the country. And with Mumbai one of just 20 districts where two-thirds of the country’s patients — and deaths — are concentrated, localities such as Dharavi are where officials are engaged in a pitched battle against the pandemic.

Opinion| When Covid hits slums

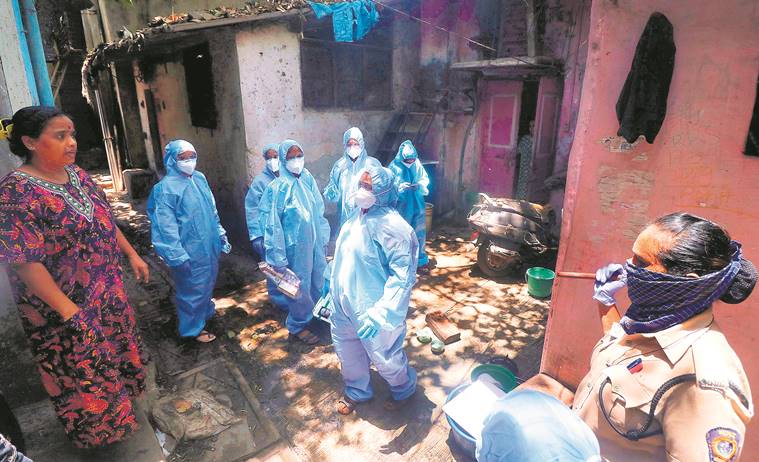

In these localities, every other alleyway is sealed off to impose a quarantine. Health workers in full PPE enter these colonies, walking through a maze of lanes to identify patients and take them to ambulances waiting on the main 90 Feet Road or 60 Feet Road, or sometimes walk them all the way to the quarantine centre nearby. It is almost like a perp-walk.

On Friday, a team from Health Post No. 2 walks into into a chawl, led by the Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) and anganwadi worker who know the locality best.

The first stop is an incorrect address, and they’re redirected to the rear end of the colony. At the second stop, the family insists it’s mistaken identity — nobody is sick. Eventually, it emerges that the neighbours had complained against the family for not completing quarantine after a contact was found positive.

Tempers run high briefly as the young man of the family emerges at the doorway and threatens to assault the neighbour who complained. ANM Vibha Kulkarni says this is common, and the team deals with the reluctant family with good humour and tact. “Put them all ‘inside’ for two weeks,” a neighbour shouts. “I’ll start with you,” retorts the ASHA leading the team. Finally, after a 15-minute standoff, clothes are pulled off the clothesline hanging outside, the male adult asks for permission to visit the public toilet, fists are stamped for the quarantine and the five members of the family walk out, two policewomen with only handkerchieves across their faces bringing up the rear of the march to the quarantine centre. Soon after, a man sprays disinfectant at the doorstep of the just-quarantined family, the can of chemical on his back bearing the face and name of a local Congress leader.

“Privacy, secrecy, genuine awareness on how to prevent the spread of the disease, good private medical care that can supplement the public health system’s work, any possibility of real social distancing, adequate water for all, all of these are missing in the slums,” says Gulzar Waqar Khan, a trader and social activist who has been helping distribute free groceries and bottles of sanitiser to Dharavi’s residents through his Hum Sab Ek Hai Foundation, set up by his father to help keep the peace during the 1992-1993 communal riots in Mumbai.

A native of Bareilly himself, Khan says he’s getting worried calls from acquaintances across the country asking if he’s okay. “People going home from Dharavi are scared to say they were living here, but hey, we’re all going to continue living here — Dharavi is not exploding,” he says. “There is nothing surprising about the number of cases here.”

Health workers in full PPE walk through lanes to identify patients to take them to the quarantine centre

Health workers in full PPE walk through lanes to identify patients to take them to the quarantine centre

***

Almost everyone who has lived in Dharavi for a few years agrees that it should have been obvious from the start that a ‘lockdown’ would worsen the epidemiological disaster that is a Mumbai slum colony. Already living in unsanitary conditions, sharing toilets, the forced sequestering imperilled people further.

On May 4, Mumbai had about 9,000 cases, growing to more than 20,000 cases on May 17 when the next lockdown was imposed, and now 36,710 as Lockdown 5.0 is anticipated. The areas that have seen the largest rise in number of cases are localities of the poor, slum colonies and chawl buildings, municipal administrative wards such as L, G South and E seeing the maximum number of cases, all regions with densely populated slums in which not more than 5 per cent have a toilet at home. They are all localities with large populations of working-class migrants rendered desperate to find a way to get home because of twin fears — destitution in the absence of wages and the sense that the disease is closing in.

In Dharavi, there were 590 cases on May 4, rising to 1,028 cases on May 14. A fortnight later, on May 29, the number was 1,715, including 70 deaths — every single resident of the slum blames the rising number on the lockdown.

Approximately 40 per cent of Dharavi’s residents are migrant workers living in the most informal arrangements, especially those without family members here, sharing a tiny 10×10 feet room with a dozen others, having lived here for less than five to six years. This segment of Dharavi’s population is now either waiting to leave or has left, on board a truck or bus or a special Shramik train.

“Sab bhaag gaye,” say the handful of workers still left in Dharavi’s Shakir Compound, 13th Compound and Sanaullah Compound, a series of informal industrial layouts on the western edge of the slum adjoining a two-metre-wide fetid gutter with pedestrian bridges across it.

The site of, until recently, a crush of workers in soot coloured clothes, blue plastic drums of caustic paints and dyes, and a sea of candy coloured granules of recycled plastic on dirty tin roofs, the hush in these industrial compounds is eerie. Over the slow downturn of the past two years, many recyclers had already shifted business to more inexpensive units in Vasai and Bhiwandi on the outskirts of Mumbai, their units replaced by garment sweatshops where workers poured in every morning by the thousands. Those units are all locked, workers having mostly left for villages and unit owners living elsewhere. Friendly stray dogs and a few pet goats roam the dusty streets of these compounds.

Sadabriksh Kanojia of Gorakhpur is among the few still living in Sanaullah Compound, looking after the plastic crushing unit for his employer who is stuck in Goa. His monthly salary of Rs 12,000 is assured, and the more strenuous tasks of heaving drums of the crushed plastic to be dried on the roof are suspended for now.

“If I wait until the boss returns, he will pay for my journey home also,” says Kanojia. Philosophical about his humble circumstances, Kanojia says he has seen completely illiterate men become ‘seths’ and those with degrees sorting plastic to make a living.

“Much of our existence is dictated by fate. Some of those returning home now may never find a job paying Rs 12,000 a month and will have to return to Mumbai eventually — our connection with this city is also fate,” he says. His children Savitri, Neeraj and Suraj have watched news reports about Dharavi, and the family is urging him to return home. “Even the poor want to be with their loved ones, you know,” he smiles. “They’re scared for me, but things are actually quite alright here.”

***

But if the the sweatshops and industrial units wear a cloak of shocked silence, the residential quarters are still crowded. “You can’t help it. If there are 30,000 people living in homes along a small alleyway, naturally 400 or 500 will gather at the medical stores, vegetable handcarts or community toilets,” says Lavgan Parmar, a 55 year-old scrap collector belonging to Karajkheda in Gujarat.

Parmar lives in Dhorwada, just off Kakkayya Street, which forms part of Dharavi’s ‘Chinna Tamil Nadu’ or small TN, tucked away behind the modern facade of the Kamarajar Memorial English School building. Dhorwada is one of the poorest parts of Dharavi, and also among the angriest now, with residents saying they have been deliberately neglected by politicians and other organisations for distribution of free groceries.

“If they’re distributing rations near the Mariamman temple, they’ll say it’s not for you, only for Tamil people. Or closer to that signboard with MLA Varsha Gaikwad’s name, they’ll say it’s only for Congresswallahs — it’s as if this portion of Dhorwada is deliberately neglected by everyone,” says Ashok Gheware, spitting disgustedly into the narrow two-feet alley separating his home from the one across.

“Distribution of relief material has become a political and caste and community game,” says Gheware, who sports a big vermillion dot on his forehead and wears what appears to be a mangalsutra and gold jewellery in multiple ear-piercings.

An HIV/AIDS worker and a self-confessed professional ‘baba’ or spiritual guru, Gheware has made it a point to collect his entire PDS quota from the ration shops to cook khichdi for neighbours. The Parmars are struggling, and Lavgan says he has had to feed his children only boiled rice and salt for days, that too because somebody offered him free rice. “We have made chapatis also of rice,” he says.

Two doors away, Ahmadi Shaikh Khatun, from Sitamarhi in Bihar, says her husband, a cook, has been without wages for nearly three months now. A mother of seven girls and an infant boy, Ahmadi used to supplement their income by running a ‘bissi’, a term for the informal mess run out of hundreds of homes in Dharavi where workers come to eat two meals a day for a monthly fee. “With workers gone, there’s no bissi work also,” she says. Her elder children have pulled out of school too, mirroring a common trend in Dharavi now.

“Education, nutrition, sanitation — these are the things we need to talk about in Dharavi going forward,” says the activist Gulzar Khan, who is about to launch a pilot project on thoroughly sanitising three public toilets repeatedly through the day, hoping this can be scaled up. Immunisation of children has taken a hit with families leaving suddenly. And children who were struggling in final years of secondary school are at danger of being pushed by circumstances into finding employment instead.

“But for now, everyone’s talking about survival alone — the middle classes are now beginning to accept charity despite the deep shame this comes with. So many apparently well-to-do families accepted food packets from us on Chand Raat before Eid.”

The poverty clock has begun to tick backward in Dharavi.

Figuratively speaking, the slum is back now where it was in the year 1896, when an outbreak of the bubonic plague ravaged Bombay, on the periphery of the big city.

The plague in Bombay was central to the drafting and enacting of the Epidemic Diseases Act that is now in force, but for Dharavi, that is not the only vestige of the plague. It took eight years, but the eventual outcome of that epidemic and the exodus of workers in that period was the formation of the Bombay City Improvement Trust in 1898 and the reimagining of how Bombayites, including the ‘natives’, would live in the future.

Around the 1920s, the Trust planned to convert the area occupied by Dharavi’s tanneries into a “salubrious” suburb, the tanning units themselves proposed to be moved to Trombay, now another sprawling slum area alongside industrial units.

That dream for a new Dharavi remained unfulfilled. Well over a century later, another crisis brings with it an opportunity. This is the time to reimagine Dharavi and resolve its fundamental questions — of housing, sanitation, healthcare and education.