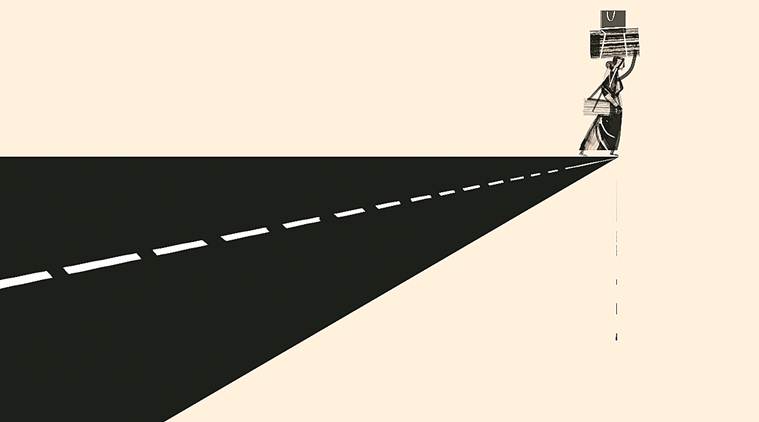

I have heard government has deposited Rs 500 a month for two months now, but I don’t have the account number or passbook with me. To withdraw the money I will have to go back to Bulandshahr. (Illustration by C R Sasikumar)

I have heard government has deposited Rs 500 a month for two months now, but I don’t have the account number or passbook with me. To withdraw the money I will have to go back to Bulandshahr. (Illustration by C R Sasikumar)

Standing next to a small, weary group in the surreally bare forecourt of New Delhi Railway Station, Ajmeri Gate side, beside bags of indeterminate shape, she is the only woman. An official of the Delhi Police walks up to the group, demands: Do you have any tickets for a train? If you don’t, you are not allowed to stand here, you must go. She doesn’t have a ticket, she says. She is Shabnam. Shabnam what? Only Shabnam, she says with a finality that belies the tentativeness that hovers over the group on a hot Monday afternoon, the start of Lockdown 4.0

I came this morning on a train from Allahabad, couldn’t have stayed there any longer without work. I am on my way to my sister’s house, who lives in village Kuchheja in Bulandshahr. Or to my other sister’s home, who lives in Faridabad. I am ready to go to either place if I get some means of transport. An acquaintance bought me an online ticket for the Rajdhani from Allahabad to Delhi last night, I thought I would find a bus from here, but they say there are none. I have very little money left. In two and a half months of the lockdown I used up whatever I had earned and kept away. I am travelling alone, I don’t know what to do.

My son says he cannot come and get me, he has no vehicle. Tum dekho (you see what you can do), jaise wahan se aa gayi waise (you find the way onwards like you did this far). His friend in Ghaziabad will pick me up from here on his motorcycle if he can get the paperwork in order. I can only ask my son for help, or my sisters’ sons in Faridabad. My nephew who drives an auto is trying to arrange for an auto driver to pick me up, take me across to the Badarpur Border, but the borders are sealed.

I can’t ask anything of my four brothers in Bulandshahr. I don’t talk to them since the divorce, they did not stand by me. You can stay with us, we will look after you, they said, but don’t take the matter to court. I did not listen to them, I got my divorce in court, after two years of separation, four months ago. My husband would beat me up badly, say he was sorry later. Par baad mein pachtaane se kya (of what use was his repentance). It was a matter of life and death, I was saving my life. Only my sisters supported me. Get married again, they tell me. But I feel if I marry again, what if he turns out to be like my husband.

Main toh bawli ho rahi hoon (I don’t know what to do), par behnein hi hain (I have only my sisters to look to).

I did not even inform my brothers or my mother (my father is dead, he was a labourer), when I left to find a job in Allahabad five or six months ago. I had worked earlier, too, in Faridabad, off and on, for almost 10 years, when I lived there with my husband and son. In the packing section, in a company that made silencers for motorcycles. For the last two years, after separating from my husband, I need to earn in order to eat, I am on my own.

In Allahabad, my job was cooking food for a group of 10-15 labourers in Civil Lines. They gave me Rs 8,000 a month, free lodging and food. I have bought an insurance policy for my old age, some money goes into that, the rest helped me through the last two and a half months. When I started the job in Allahabad, hisaab lagati thi (I made calculations): At the end of the year I would have Rs 50,000-60,000, budhape mein baith ke khaoongi (will sit back in my old age). I am 35, but I feel older, my body is broken by my husband’s beatings. My eyesight has gone weak.

The labourers who employed me in Allahabad set out for their homes on foot when the lockdown began. I had no strength to walk, and where would I have stayed in the night. First I thought this corona is a lie. Then work started shutting down, labour began walking home. I went to the bus station only to return because there was no bus, twice. I was running out of money. They told me, rashan bat raha hai (free rations are being distributed). I did go to one place, par sharm aayi (I felt shame). We had to stand in line, and what would I do with only rice and flour. I also need oil, spice and vegetables to eat. Bheek nahi maang sakte (I cannot beg). I don’t have a ration card, have a zero balance account. I have heard government has deposited Rs 500 a month for two months now, but I don’t have the account number or passbook with me. To withdraw the money I will have to go back to Bulandshahr.

I asked someone who lived nearby, give me some money, and I will donate that amount in your name to the masjid when I am able, but he didn’t. Another person in the neighbourhood gave me Rs 200, 5 kg atta, 1.5 kg dal. And then Rs 500 more. I got Rs 200 from someone else. Now, if I could get to the straight road to Bulandshahr, I will discard one of my bags, walk with the other one to my sister’s home.

When I was young, my parents did not send me or my sisters to school, my brothers studied a bit, it was a double standard. I had to wear the burqa after I got married. After I separated from my husband I wore it to hide from him. He would beat me if he so much as saw me on the road. I took off the burqa in Faridabad, where we were in a mixed neighbourhood. In Allahabad, I would wear the burqa out of sharm, to avoid the curiosity of strangers. I love the city because it gives me the option to wear the burqa or not to. I was fearful in the village, even though my family was with me. The toilet was outside, I had to cross the courtyard to get to it, so I would try and finish everything by 10 pm. I was afraid to open my door after that. Later, I was afraid of my husband.

Dar nahi tha sheher mein (in the city I felt no fear). In Faridabad, often after finishing work in the company at 7pm, I would go to my sister’s place, eat with her, and then go back to my room. In Allahabad, I didn’t go out much, only to the provision store, to buy vegetables and to the medicine shop. I can’t read or write, if I went somewhere, how would I get back. A girl who lived nearby said she would take me out in her brother-in-law’s car. She was in a love marriage. You can buy everything you want in the city, even at night. I want a life where I can work, tire myself out, sleep. Dhyan bat jaata hai (you can take your mind off your troubles).

Gaaon toh hamein achcha lagta hi nahin (there is nothing of the village that I miss in the city).

I had never even seen the outside of a school, how could I possibly dream. “Madam” ban jaayein, auron ko padhayein-likhayein (I wanted to be a teacher, teach others to read and write). My son studied only till class 7 or 8 because of the constant fighting at home. I wanted him to have a sarkari naukri (government job). He sells phones. He should have a good life, live like a hero. He is very good looking, has a sharp mind. After this is over, he should go to Bombay, try his luck in TV or film.

I am in two minds, scared, should I marry again. There is a man I know in Civil Lines in Allahabad, who says he will marry me and find welding work in Noida. I have heard that in Noida you can find lighter work for higher pay. I could do packing work again, or set up a vegetable stall. I might go there after a few days at my sister’s place, once this is all over. I work, I earn and then it all empties out. I must get back to work.

Shabnam, 35, born in village Tatarpur, district Bulandshahr, UP, has one son, 18, who lives with his father, a vegetable vendor. She is on her way from Allahabad, where she worked as a cook, going to Faridabad, Haryana, or Bulandshahr. She spoke to VANDITA MISHRA

Opinion | When Covid hits slums