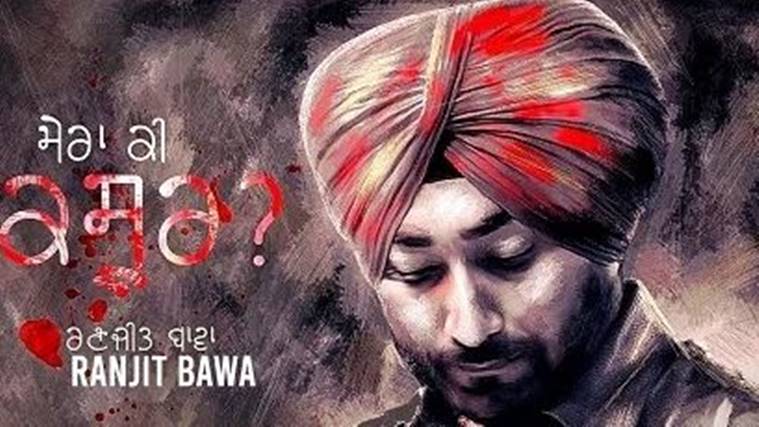

‘Mera ki kasoor’ by Ranjit Bawa has landed in a controversy with many terming the song ‘anti-Hindu’

‘Mera ki kasoor’ by Ranjit Bawa has landed in a controversy with many terming the song ‘anti-Hindu’

Gurdaspur-born Ranjit Bawa is a pop sensation in Punjab and among Punjabis elsewhere in the world. His songs are often part of neatly choreographed dance performances in weddings, and though he hasn’t marked his entry into Bollywood yet, his popularity soars high, often topping UK Bhangra charts.

But Bawa’s latest Mera ki kasoor, a song taking on the caste system, and atrocities on the poor and the Dalit has ruffled some feathers. Kasoor is a welcome departure from the gun-yielding-whiskey-drinking-Jatt-wooing-women-in-his-Lamborghinis kind dance numbers the region is best known for in the mainland.

Bawa’s song seeks to call out the centuries-old caste system using religious connotations— Kaisi teri matt lokaa kaisi teri budh aaa; Bhukhiyan layin mukiyan te pathraa layin dudh aan (What kind of mind and thinking do you have? You throw stones on the hungry but feed milk to stones).

Faced with multiple FIRs, including by the BJP’s state youth wing, for “hurting religious sentiments of Hindus” Bawa has apologised for the song—composed by Bir Singh–and taken the song off YouTube. It is currently available on music streaming apps.

Mera ki kasoor is not a peppy number like many others on Dalit pride, Bawa’s is a song from the perspective of a poor man whose identity is defined by the discrimination he faces while the inanimate receive ostentatious showering of love and wealth. At one point, he warns of war if he reveals the truth. “Ohh je main sach bohtan boleya te mach jana yudh aan,” he says, before going on to compare the cursed shadow of a poor man to that of the ‘holy’ urine of a cow. “Greebde di shoh maadi gau da moot shud aan(/If I tell the truth, there will be a war. The shadow of a poor man is impure, but cow urine is pristine)”

Evoking Saint Ravidas, Singh, through his composition, has a central theme: “Oh je main maade ghar jammeyan; te mera ki kasoor aan (I was born in a poor house, what is my fault?)”

A Jatt sikh himself, Bawa is known to confront uncomfortable realities head on. His single Jatt di akal has references to the political upheaval in Punjab in the late 80s and early 90s.

The controversy surrounding Mera ki kasoor, however, has brought the focus once again on the narrative of Dalit identity in the Punjab music scene that has existed for years now, taking on, and countering, the overwhelming theme of Jatt pride.

The first name that comes to mind while discussing Dalit assertion in Punjabi pop culture is Ginni Mahi, who brought the resurgence of ‘Dalit pop’. In her single Danger Chamaar released in 2016, Ginni, then only 17, embraced a hateful casteist slur and made it her own. The song is markedly different from those by, say, Jasmine Sandlas, Bani Sandhu, Kaur B and other popular women singers of Punjab, in that it pays homage to Ambedkar and Saint Ravidas, but little else grabs your eyes.

Ginni’s song starts with an upbeat Bhangra tune, goes on to show men with tattooed arm flexing their muscles in what appears to be a garage, but these are not the Jatts eulogised by the late Surjit Bindrakhia, or Sidhu Moosewala, these are Chamars, and “more dangerous than weapons” at that.

“The time has come to shake off the historical baggage and restore respect to this word. How long will we dread the word which has only fallen into our ears as an insult?” she had then told The Washington Post in an interview.

In the 80s, Dalit singer Amar Singh Chamkila, the Elvis Presley of Punjab, shone bright among the stars of the region’s music industry. Although he did not speak on Dalit identity, his songs were provocative to say the least. Drug use, extra marital affairs, violence against women, the toxic masculinity of a Punjabi thug were all themes of his hard-hitting music. Chamkila found his way into the industry and was unabashed about his success, and the controversies that followed it.

At a time when Heer and Ranjha were being epitomised, only he could compose lyrics on an illicit affair, examining a coy village bride taking a shower while her brother-in-law fixes his eyes on her.

“Tera Vadda Veer Mera Jeth Chada

Mori Cho Takkda Reha Khada

Main Ragad Ragad Pinde Nu Saaban Laundi Si

Oh Tacked Reha Ve Main Sikhar Dupehre Nahaundi Si”

(Your elder brother, my brother-in-law who is single; is spying through a hole; I was slathering my body with a soap; he kept looking as I continued to shower in the afternoon)

Chamkila’s unsolved murder in 1988, when the state was in the midst of a Khalistani insurgency, was even made into a film Mehsampur.

Ankhi Put chamara di, loosely translated as ‘the proud sons of Chamar’ is another song that comes to mind when discussing Dalit assertion. Mind that this number by SS Azad has all the elements you would find in a typical Punjabi song, complete with rifle firing and a proud Sardar accompanied by his entourage. But most significantly, it counters the dominance of the Jatt.

“Ho gaddi uttee ankhi chamaar likhwaaya, dabb vich pistal londono mangwaaya (We have inscripted ‘chamar’ on our cars, our pistols are from London”)

“Paer aa zameen ute ambaran nachaondi; aan ate shaan naal zindagi zeeonde han;

asin kalam banayi talwar; asin kalam banayi talwar, ni kehra panga le lau, ni kehra panga le lau; saanu akhde ne ankhi chamar, ni kehra panga le lau haaye”

(Our feet are on the ground, we live our lives with pride and respect; we made pen our sword, who will mess with us, we are sons of chamar)

The Chamar is a counter to the Jatt, but similar to him. He is a tall proud man who drives an SUV, and is fearless, even breaking laws and jumping red lights. He is no less than a Jatt and the point is conveyed.

It will be incorrect to credit this as an “awakening” of new artists. Music proclaiming Dalit identity is not a new phenomenon and can go back several years with songs like Dhee Chamara Di by Rajni Thakkarwal, Tor Chamara Di by Raj Dadral, or those by singer Roop Lal Dheer.

But Dalit participation has revolutionised Punjabi music like little else. Since Sikhism is widely considered to be an egalitarian religion, songs like Bawa’s Kasoor or the plenty others on Dalit pride, expose faultlines in the culture, while also challenging it at the same time.

At the end, it is a revolution we can dance on.