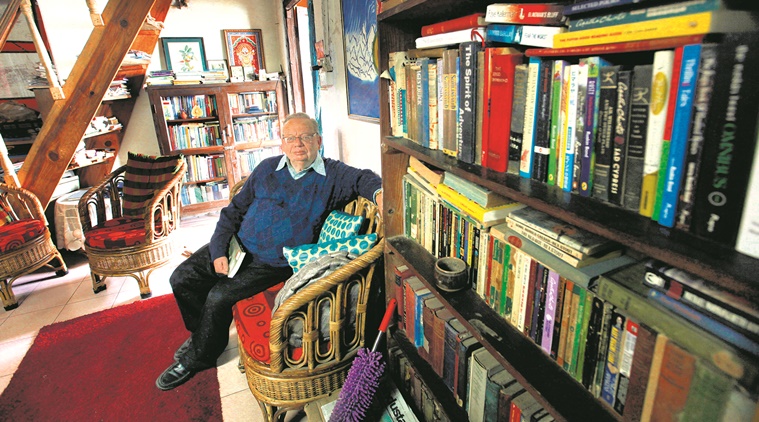

Ruskin Bond, an Indian author of British descent at his house at Landour Cantt. in Mussoorie. (Courtesy: Ravi Kanojia)

Ruskin Bond, an Indian author of British descent at his house at Landour Cantt. in Mussoorie. (Courtesy: Ravi Kanojia)

Long before the world discovered the virtues of windows in this season of social distancing and staying home, Ruskin Bond let the world in through his. With the mountains on one side, the valley below and the road ahead, the view from Ivy Cottage in Landour, a corner of the hills that was once the headquarters of the American missionary community in India, is varied. “A long and ne’er-say-die search for the perfect window. This would be one way to sum up my life,” writes Bond, one of India’s most loved and prolific writers, in A Book of Simple Living (2015, Speaking Tiger). “Windows are all important, and not just for writers. I get the sunrise on my bed first thing in the morning. It wakes me up,” he says. At his previous home, Maplewood Lodge, he found the solitude he sought, living next to the forest and writing from his window seat. Many of his best-known short stories, that make up classics such as The Night Train at Deoli (1988), Time Stops at Shamli (1989) and Our Trees Still Grow in Dehra (1991), emerged from that workstation.

It wasn’t lonely though. A small plump squirrel would climb on to his window-sill, “a little out of breath with the effort” and eat groundnuts out of his hand, and, at night, the moths would beat softly against the window panes. “Mussoorie hasn’t been this quiet since I came here in 1963. There were only two taxis then. I think, we have about 600 now. But the streets are near-empty,” says the author, who was born in Kasauli, grew up in Jamnagar, journeyed through Dehradun, England and Delhi, before putting down roots in Mussoorie.

From his room now, he can see the road but the hum of everyday life is missing. The birds seem to have decided to compensate for the missing footfalls by increasing their number of flights. “In the early morning, I see far more birds than I used to and a greater variety, even some that hadn’t been coming before. Yesterday, there was an orange minivet. It’s more of a forest bird, it did not venture here earlier. Usually you will see parrots in the plains but they have been coming up for a holiday now that the tourists aren’t,” says Bond.

The hill station that sees traffic jams stretching to hours in the summer is now almost entirely made up of its local residents. “Mussoorie, of course, will miss the tourists because it’s a town that thrives on tourism. All the business people are suffering,” he says. The days are quieter and the trickle of tourists, book lovers and even honeymooners up the stairs to Bond’s room, whose visits asking for blessings have always perplexed the author who has remained single lifelong, has dried up. Will the ease with which strangers turn up at writers’ doors, join and leave conversations and the intimacy of touch that is such a big part of what India is, change in a world scarred by COVID-19? “In many ways, India is an informal sort of a country. In some other countries, you would be looked on with suspicion, whereas here it’s perfectly natural to talk to a stranger about the journey, or to grumble or make a complaint and everyone joins in,” he says. The fear of the virus may make people wary of each other but Bond says, “I think people will go back to doing what they were before. We go back to old habits. In India, it’s hard to break with custom.”

Writing for a living from the 1950s, when he was a young man of 21 to now, when he turns 86 on Tuesday, Bond has taken us through the natural world, past mofussil towns and to the deep well of solitude. This, he feels, could be a moment to review and reorient our relationship with nature. “There is a feeling among people that this, to some extent, is the outcome of human interference with the natural world. I think it was Thomas Hardy who said God created a beautiful world and left it to us to look after it, which we didn’t do too well. Hopefully, we will take better care of this wonderful inheritance,” he says.

It may also be a time to connect to ourselves. “Maybe people will also get a chance to discover themselves in this enforced solitude, to become more thoughtful because we can’t rush around as we used to, and we must try and make life as simple as possible to be reasonably happy and avoid complications. To live within one’s means and not be overambitious, that’s the road to contentment, if not happiness. Of course, it may be tougher to make a living now for sometime,” says Bond.

As someone who always worked from home, his day hasn’t changed much, maybe got busier, writing, and reading out stories for All India Radio, dipping into his rich repertoire, narrating a ghost story, a humorous anecdote and the tall tales of Jim Corbett’s khansama. The writer promises a new offering soon.

“I have written some 10,000 words during the lockdown. They are partly philosophical, thoughts and observations. So far the title is, ‘Where have all the people gone?’ But that sounds rather pessimistic. I will perhaps change it to ‘Have a Wonderful Life’,” he ruminates. That’s a dose of optimism we can all do with in these uncertain times. We could also turn to the last lines of his autobiography, Lone Fox Dancing (2017), “I’m afraid science and politics have let us down. But the cricket still sings on the window-sill.”