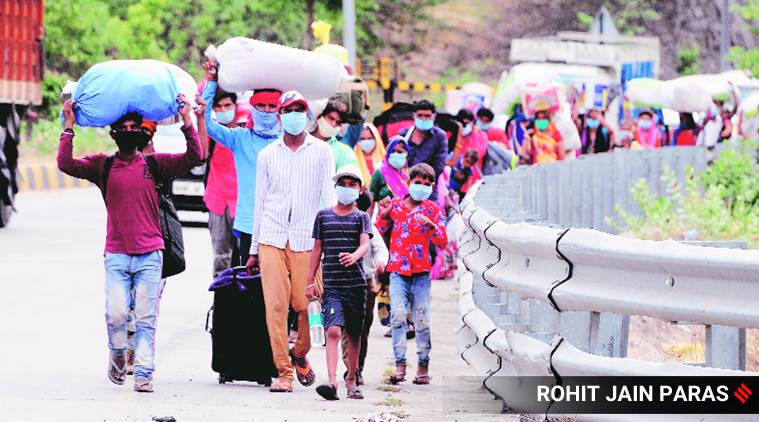

Migrant workers in Jaipur walk towards their respective hometowns and villages (Express photo by Rohit Jain Paras)

Migrant workers in Jaipur walk towards their respective hometowns and villages (Express photo by Rohit Jain Paras)

The scheme to provide free food grains and rental housing support to labour migrants announced by the finance minister, Nirmala Sitharaman, on Thursday — if implemented — can spur meaningful change when it comes to ameliorating urban disparities in India.

The opening up of work limitations for women, the “one nation, one ration card” scheme, universal minimum wage, concessional rental housing and the conversion of government-funded housing into affordable rental housing complexes are steps in the right direction. However, to ensure that these schemes reach their intended beneficiaries, we need a critical appraisal of the current housing conditions of labour migrants.

In the last three years of my doctoral research in Delhi NCR, I have been attempting to piece together how the housing question of labour migrants has been addressed in the extended urban parts of the region. I have looked at three manufacturing towns in particular: Udyog Vihar on the border of Delhi NCT, IMT Manesar located on the border of Gurgaon district, and RIICO Bhiwadi, located on the border between Rajasthan and Haryana.

What emerged as a red thread in my study is that the housing for labour migrants has been addressed through its externalisation into the villages on whose agricultural land these manufacturing towns came up. Workers’ housing was considered as an unprofitable infrastructure and thus either externalised or never built. To fill in this critical housing provision, the villages around these manufacturing centres have developed housing tenements for labour migrants through the plotting of the remaining agricultural cadasters. The tenements in these villages that are spread across a vast geographical region spanning over a 100 km bear a striking resemblance.

These tenements are multi-storey concrete structures usually made up of rooms measuring between 100–120 square feet in area, shared by a family or a group of single migrants as a multipurpose living space. These rooms are organised along long circulation corridors that also serve as ventilation shafts with shared toilets and water taps usually located at the end of these corridors.

In total, over half a million migrants are housed in such tenements in settlements such as Kapashera and Dundahera near Udyog Vihar, in settlements around IMT Manesar, and an equal number in the settlements around RIICO Bhiwadi. There has been a blackboxing of these settlements as urban villages, and their transformation remains officially invisible through dual land, and population registers. The migrants inhabiting the tenements often receive no proof of residence, consequently no ration cards, and are counted in their villages of origin rather than in the ones they inhabit.

Take for example Naharpur Kasan, a settlement adjoining IMT Manesar. The settlement is considered a rural village under the current census classification with a population of just under 10,000. However, the Public Health Centre in Manesar estimated last year that over 85,000 people had to be vaccinated. Yet, Naharpur Kasan is served by a mere eight ASHA healthcare workers, and has little in terms of infrastructure apart from some structures and water ATMs developed through corporate philanthropy.

This ingenious space maximisation and black boxing, while allowing the tenement owners to accumulate vast rental incomes, has kept the migrants in a situation of permanent temporariness. The migrants pay exorbitant amounts to access housing and basic services, which ideally should be a public right. Often paying anywhere between a third to half of their monthly income as rent, but without rental agreements or the possibility to exert tenancy rights on their living spaces. Furthermore, the compliance and temporariness of the workers in these settlements is enforced through coercion and physical violence on the part of the landowners.

During the COVID lockdown, it was this blackboxing that gave rise to various forms of overt and unspoken violence against the migrants. During the lockdown, I was in regular touch with the migrants, labour activists and local NGOs. Mixed responses emerged in these conversations: Some spoke of a few tenement owners expressing solidarity, preparing and distributing meals for people, while others reported the use of physical violence for rent collection.

This blackboxing of workers’ housing — limited not only to Delhi NCR, but common to metropolitan expansion all over India — has been in part responsible for the heartbreaking scenes of the exodus we have been witnessing. The growth story of Indian metropolitan economies is built on the casualisation not only of labour but also of the housing question of migrants.

The construction of new, affordable housing complexes to replace these settlements will be a mammoth task. It will, however, be much more productive to acknowledge the rental-housing gap these settlement transformations have bridged, and consolidate them as working-class neighbourhoods. This can be done through introducing social-physical infrastructures in these settlements. Such measures can improve their liveability and create pathways for the workers to access and own them.

The writer is an architect and doctoral researcher with Centre for Research on Architecture, Society and the Built Environment