With remittances tapering and the tourism sector down, Kerala must focus on a scientific and profitable agriculture sector

A quintessential trailer of the protracted exit from national lockdown began playing out, quite appropriately, on May Day. The curtain-raiser has been about 1,200 migrant workers being allowed the first special train from Telengana to Jharkhand. As the third extension of the lockdown got underway, many other states followed suit.

The southern state of Kerala too is seeing a bulk of migrant workers leaving for their home states. This mass exodus will leave a big void in the state which predominantly depends on outside labour. In the weeks and months to come, when the economy slowly opens up and tries to get back to the old ‘normal’, this missing workforce could be the first of the four predominant problems the state will face.

A second is the return of a large number of expatriates, a good majority of them from the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi Arabia. Many will be returning after losing their jobs, and the State will have to find ways to open avenues that could probably employ them.

A third concern would be the long-term slump in tourism, which accounted for about 10 percent of Kerala’s revenue. A fourth would be on how the State plans to revive its economy, and the role agriculture will play in it.

The Great Return

In the first phase of the evacuation will see 80,000 Non-Resident Keralites (NRKs) returning back to the state. Once the travel restrictions are lifted, the number of returning NRKs could easily double as there are a minimum 2.5 million Keralites in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) region. With GCC economies slipping on low oil prices and a large number of expats likely to return, remittances from the Gulf is expected to fall. Inward remittances play an important part in injecting life into the economy, especially Kerala’s where it is about one-third of the state’s GDP. Cautious estimates predict a 15-20 percent fall in remittances this year.

The Pinarayi Vijayan-led Left government has put in place a massive quarantine infrastructure that will take care of the thousands of home-bound NRKs — the challenge will be to gainfully employ them.

What the state desperately needs is a plan that will lead in a new direction. Kerala needs to snip off all emotional baggage that drags it down — the prime one being the white elephant called rubber cultivation.

Worn Out Rubber

For decades rubber-cultivating states in India reaped the benefits of high rubber prices; but, now the time has come for a reality check. Today rubber produced and imported from Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia at much lower prices has made widespread rubber cultivation in India non-viable. Thus, the small planters need to move and leave it to the big players who have high acreage and low overheads working to their advantage.

Presently, there are over 1.2 million small scale rubber planters in India, with an average holding of one acre, and over 85 percent of them are in Kerala. Many of those would belong to the NRKs returning home with no other means of livelihood.

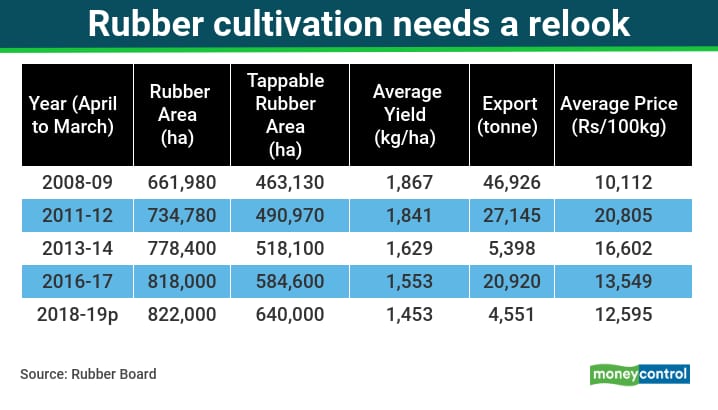

According to the Rubber Board, the total area under rubber cultivation across India in 2018-19 was 822,000 hectares. Of this, the tapped area of 640,000 hectares produced 651,000 tonnes. The national requirement was 1,211,940 tonnes, necessitating the import of 582,351 tonnes.

The gradual erosion in productivity over the decade should give a clearer picture as to why rubber cultivation needs a relook. If in 2008-09 the productivity was at 1,867 kg/hectare, it plummeted to 1,453 kg/hectare by 2018-19 (See table below).

Adding to this dipping price is the decrease in crop yield and cultivable area. In 2018-19, actual tapping took place in 78 percent of the cultivable land. Last year, this was 70 percent.

In addition to this, rubber trees past their lifespan are a concern. Not many farmers can afford to replant rubber as there is a gestation period of 8-9 years before the trees can be tapped again. If the focus was to remain on rubber and replanting was to go about, it would mean that about 40 percent of the land said to be under rubber cultivation, most of it in Kerala which would come to about 280,000 hectares, would remain unutilised.

It is here that the Kerala government’s decision to develop 109,000 hectares of waste land, with a stress on 25,000 hectares of fallow land, for cultivating food crops is missing the fine print. Why focus on waste land when there is ready-to-be-farmed 280,000 hectares of fertile land? It is important that the Left government has a vision for this 280,000 hectares because it could be the lifeline for the thousands of returning NRKs.

Archaic Land Laws

Kerala’s plantation sector goes beyond rubber. About 719,686 hectares of cultivable land in Kerala is divided between rubber (550,840 ha), coffee (84,987 ha), tea (30,205 ha), cardamom (39,730 ha), and cocoa (13,924 ha). A focus on these crops is yielding diminishing returns: In 2011, if the revenue was Rs 23,000 crore, last fiscal it went down to Rs 8,000 crore.

The culprit is the Kerala Land Reforms Act, 1963, wherein the government has decreed what is to be grown where. This needs to change.

Reviving The Plantation Sector

Expert speak is that one-third of the land currently under the plantation sector is ripe to be brought under horticulture and the aggregate production will be none the worse for it. The high ranges are geographically suited for growing an assortment of cash crops, such as the litchi, passion fruit, avocado, etc.

Accompanying this could be the setting up of a range of food processing units. The horticulture sector is growing nationally at 17 percent, while in Kerala it is 24 percent.

To facilitate these initiatives the State could turn to a PPP-modelled ‘Plantation Land Bank’ and open a lucrative FDI window in this sector.

Recalibrating Human Resource

At a time when governments around the world are busy figuring out ways to restart collapsed economies, the Kerala government needs to be focus on what appears to be a no-brainer of a solution to provide employment and revive the agriculture sector. This will make the economy less reliant on remittances, make it more robust and prepare it for future exigencies.

The state can no longer pamper itself by paying astronomical daily wages at Rs 800 for unskilled workers and Rs 1,200 upwards for skilled workers. The disparity is quite unreal, as, in most other states it would read Rs 300-400 (unskilled) and Rs 600-700 (skilled). This has meant that Kerala has priced itself out of the competitive market for farm produce, manufacturing and construction cost. A revision of daily wages would also mean that ‘guest workers’ may not find it lucrative to return to Kerala. This gap can be filled by returnee NRKs.

An Agrarian Future

The thrust would have to be on a modern, scientific, planned and profitable agriculture sector that will gainfully employ not only the present but the coming generations as well. Only this will herald the onset of an agrarian economy with allied value-addition leading to earning valuable foreign exchange.

For many decades, the mantra describing the work ethos of Keralites has been: a hardworking lot outside the state, but a lethargic bunch on home turf. If Kerala has to come out of this pandemic and stand tall, it will have to rewrite this axiom.

Vinod Mathew is a senior journalist based in Kochi. Views are personal.Special Offer: Subscribe to Moneycontrol PRO’s annual plan for ₹1/- per day for the first year and claim exclusive benefits worth ₹20,000. Coupon code: PRO365