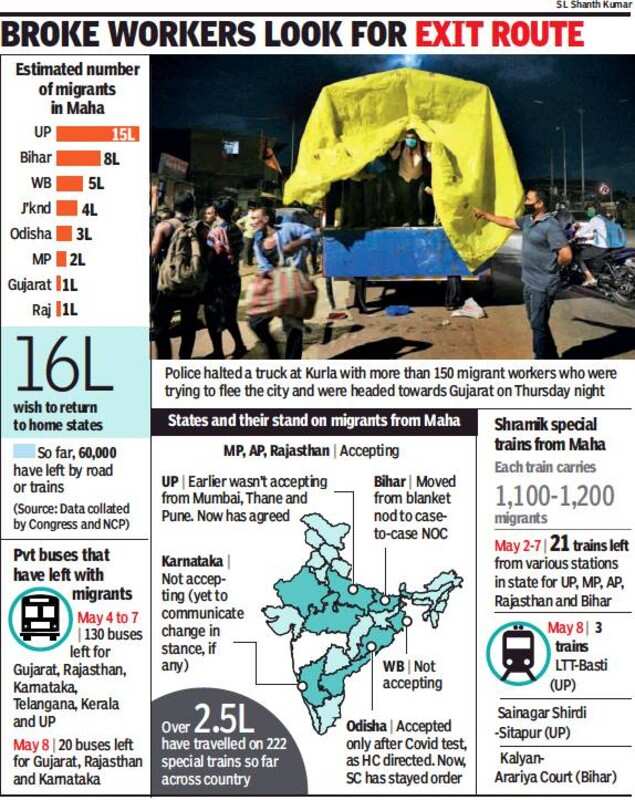

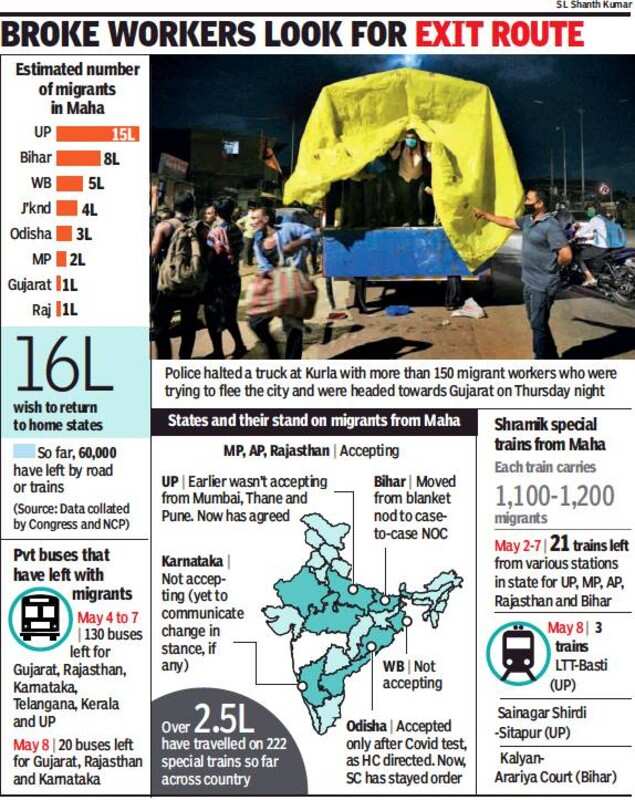

MUMBAI: The exodus of migrants from Maharashtra is no longer confined to those hovering over the poverty line, the masses who made ends meet through daily workmen wages and contractual jobs. A large section now on the long march or riding the interstate bus home are from the Rs 15,000-20,000 income strata employed in industries ranging from jewellery and e-commerce to garments and hospitality.

The gig economy had lifted many by a few notches on the income ladder, but not enough to build a security net that would sustain them during a months-long lockdown. “It is becoming difficult to survive in the city with no job and money. The only way out is get back to my village and do some farming,” said Mohan Bavaliya, 32, from Rajkot. He was employed with a jeweller in Mira Road who paid him Rs 10,000 to tide over the lockdown, but with no end in sight, he has been left to fend for self and family. Bavaliya said a vehicle owner had promised a passage home; he was on his way to a pick-up spot near Kashimira police station when a TOI correspondent met him.

Mumbai-Ahmedabad highway is the route for a constant flow of refugees fleeing the economic miseries wrought by the pandemic. Unlike the first wave—of mostly homeless labourers—who left for Gujarat, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh days after the lockdown was first announced, this time the majority comprises families who are no longer able to pay rents or manage household expenses. They had access to drinking water, sanitation, energy, education, housing and healthcare, but paid for it. Unwilling to survive on handouts, they have now chosen to return to their hometowns rather than depend on the whims of an adopted state.

“We stayed in a rented room in Kandivli but had to vacate as we can’t afford the rent. We decided to start walking and get lifts en route,” said Harsh Sahariya, 30, from MP. Employed at a mobile shop at Indraprastha shopping centre in Borivali, he said he barely got paid in March and has run out of cash. He and some room-mates, all of whom earned Rs 10,000-15,000, said they were not willing to beg for a living.

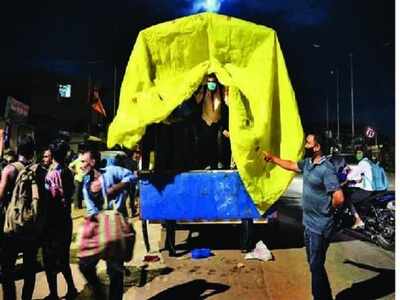

TOI interacted with several who said Lockdown 3.0 was the tipping point. The common reasons were that in the last 40 days they had no work or wages and savings had dried up while food supplies were erratic. Cops said by sunset the highways are now flooded with such people. “These migrants have now started walking after dark. That way they manage to sneak out of the city,” said a cop manning the Ghodbunder Road junction.

A group on Thane-Belapur road en route to Dungarpur in Rajasthan on Friday, said they had filled up inter-state travel forms and paid for medical certificates declaring them “healthy”. But since their turn on the Shramik special trains to their state would take a while, they had decided to walk. “We are not depending on government anymore to take us home," said a member of this group, Kranti Kumar.

The main problem now is the perception that Mumbai is spiralling out of control, said Brinelle D'Souza, assistant professor on TISS' Mumbai campus. “They fear they will get infected or the lockdown will continue through the rains. Government can still reach out to them, open up institutions and ensure they get good food and shelter. Many have complained about quality of food they receive," she said.

The gig economy had lifted many by a few notches on the income ladder, but not enough to build a security net that would sustain them during a months-long lockdown. “It is becoming difficult to survive in the city with no job and money. The only way out is get back to my village and do some farming,” said Mohan Bavaliya, 32, from Rajkot. He was employed with a jeweller in Mira Road who paid him Rs 10,000 to tide over the lockdown, but with no end in sight, he has been left to fend for self and family. Bavaliya said a vehicle owner had promised a passage home; he was on his way to a pick-up spot near Kashimira police station when a TOI correspondent met him.

Mumbai-Ahmedabad highway is the route for a constant flow of refugees fleeing the economic miseries wrought by the pandemic. Unlike the first wave—of mostly homeless labourers—who left for Gujarat, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh days after the lockdown was first announced, this time the majority comprises families who are no longer able to pay rents or manage household expenses. They had access to drinking water, sanitation, energy, education, housing and healthcare, but paid for it. Unwilling to survive on handouts, they have now chosen to return to their hometowns rather than depend on the whims of an adopted state.

“We stayed in a rented room in Kandivli but had to vacate as we can’t afford the rent. We decided to start walking and get lifts en route,” said Harsh Sahariya, 30, from MP. Employed at a mobile shop at Indraprastha shopping centre in Borivali, he said he barely got paid in March and has run out of cash. He and some room-mates, all of whom earned Rs 10,000-15,000, said they were not willing to beg for a living.

TOI interacted with several who said Lockdown 3.0 was the tipping point. The common reasons were that in the last 40 days they had no work or wages and savings had dried up while food supplies were erratic. Cops said by sunset the highways are now flooded with such people. “These migrants have now started walking after dark. That way they manage to sneak out of the city,” said a cop manning the Ghodbunder Road junction.

A group on Thane-Belapur road en route to Dungarpur in Rajasthan on Friday, said they had filled up inter-state travel forms and paid for medical certificates declaring them “healthy”. But since their turn on the Shramik special trains to their state would take a while, they had decided to walk. “We are not depending on government anymore to take us home," said a member of this group, Kranti Kumar.

The main problem now is the perception that Mumbai is spiralling out of control, said Brinelle D'Souza, assistant professor on TISS' Mumbai campus. “They fear they will get infected or the lockdown will continue through the rains. Government can still reach out to them, open up institutions and ensure they get good food and shelter. Many have complained about quality of food they receive," she said.

Coronavirus outbreak

Trending Topics

LATEST VIDEOS

More from TOI

Navbharat Times

Featured Today in Travel

Quick Links

Kerala Coronavirus Helpline NumberHaryana Coronavirus Helpline NumberUP Coronavirus Helpline NumberBareilly NewsBhopal NewsCoronavirus in DelhiCoronavirus in HyderabadCoronavirus in IndiaCoronavirus symptomsCoronavirusRajasthan Coronavirus Helpline NumberAditya ThackerayShiv SenaFire in MumbaiAP Coronavirus Helpline NumberArvind KejriwalJammu Kashmir Coronavirus Helpline NumberSrinagar encounter

Get the app