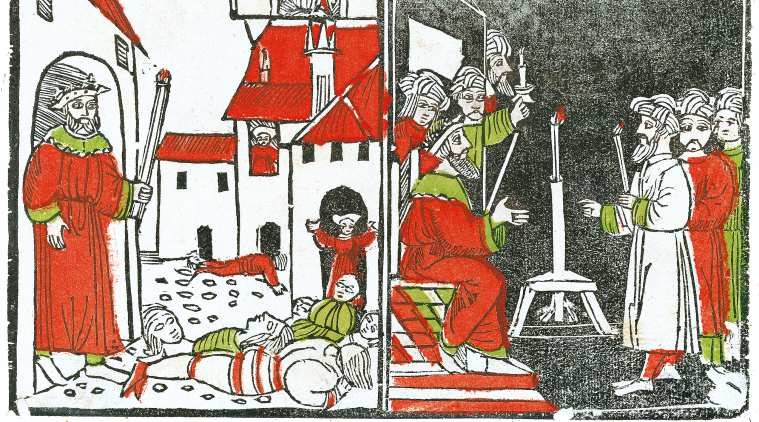

A Spanish 15th century woodcut, Massacre of the Firstborn and Egyptian Darkness, depicts a Bibilical plague. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

A Spanish 15th century woodcut, Massacre of the Firstborn and Egyptian Darkness, depicts a Bibilical plague. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Every disease is a story. It has a beginning, middle and, hopefully, an end. Some illnesses are little more than anecdotes or riddles. Others are parables and allegories. A few grow into epics, containing a multitude of episodic tales, one leading on to another. The novel coronavirus, which is responsible for COVID-19, sounds like something out of science fiction. It is still in the process of being deciphered, a mystery told in a language that has yet to be translated. Nevertheless, it spreads among us with very real and immediate results. In early January, my wife, Ameeta, and I both got sick with pneumonia in Denver, Colorado. When we were tested for the flu, the results were negative. Our symptoms — fever, cough, shortness of breath, inability to taste food, etc. — seem to match everything I’ve read about COVID-19. The worst of it lasted two weeks and for half of that time, I needed supplemental oxygen to breathe. The doctors who treated us offered no diagnosis beyond pneumonia and prescribed drugs that had little or no effect.

All of this happened before the disease began killing people in large numbers around the world. Phrases like “social distancing” and “shelter in place” hadn’t yet become a regular part of our vocabulary. Perhaps, one of these days, when medical technology catches up with the pathogen, Ameeta and I will have an opportunity to get tested for antibodies and learn whether or not our pneumonia was a result of COVID-19. Until then, it is a story without a clear conclusion, full of enigmatic ambiguity, like something Milan Kundera might have written.

Of course, doctors can be storytellers too, as Abraham Verghese demonstrated in his powerful memoir of the AIDs epidemic, My Own Country (1994). Through the personal traumas and collective fears of his patients in the Smoky Mountains of rural Tennessee, Verghese recounts a terrifying yet compassionate tale of infection, treatment and death, as well as the constant hope for a cure. While the Human Immunodeficiency Virus may be the main character in Verghese’s book, it is the stories of the people it attacks that allow us to understand the disease.

Over time, the many ways in which we tell our stories have changed. While oral traditions continue today, they have been replaced by succeeding generations of new narrative devices, including social media. The epic of Gilgamesh, one of the first stories ever told, was preserved on clay tablets impressed with a cuneiform script that was decoded by modern scholars four millennia after it was written. Much of Gilgamesh’s story revolves around the hero’s search for a healing herb that will bring his friend, Enkidu, back to life. Similarly, the plagues of ancient Egypt are chronicled in hieroglyphics on the walls of their victim’s tombs, as well as in Jewish and Christian scripture.

As a writer who works at home, I am fortunate that my daily routines have been largely unaffected by the many restrictions and anxieties that the contagion has produced. At the same time, it is impossible to ignore the widespread fear, disruption, unemployment and hardship that the coronavirus has unleashed on the world. The death toll is tragic and seems to be rising in a merciless curve. Confusing, conflicting rumours spread through the internet, adding to a helpless feeling of being besieged by an invisible, insidious force that respects no borders and overwhelms its victims without warning.

Travel has been severely restricted. Most of us are quarantined, locked-down or subjected to curfews in an effort to slow the progress of this disease. Whatever metaphors we use to describe these desperate conditions, they seem inadequate and trite. Even the constant talk of “waging war” against the virus, a favourite analogy employed by world leaders, doesn’t adequately describe the kind of response that is required. As human beings, our adversarial nature demands an enemy and since the virus itself is faceless, we often transfer our hostilities to those we blame, telling and retelling stories that point fingers in various misconceived directions.

Up until the beginning of the 20th century, Tibetan authorities only opened Himalayan passes for the summer, after ensuring that there was no cholera or other epidemic on the other side. If any news of a disease was reported, the passes were kept closed and no traders, shepherds or pilgrims were allowed to cross over into Tibet. Travellers have always carried their maladies with them just as they transport and transmit stories. During the current global pandemic, our journeys have been curtailed and most borders have been sealed to try and contain the virus. At the same time, stories continue to circulate, whether we read them in books or find them online. For any storyteller, the fundamental question will always remain, “What happens next?” even if we don’t know the answer.

(Stephen Alter is the author of Wild Himalaya: A Natural History of the Greatest Mountain Range on Earth)