Though footfall has gone up, Home Needs Supermarket has had to face disruptions in procurement and distribution (Express Photo by Gajendra Yadav/Praveen Khanna)

Though footfall has gone up, Home Needs Supermarket has had to face disruptions in procurement and distribution (Express Photo by Gajendra Yadav/Praveen Khanna)

Baking powder to cornflakes, vegetables to chips, bread to eggs, milk to oil. The Indian Express follows the delivery chains running night and day across Mayur Vihar, East Delhi, which saw the Capital’s first coronavirus case, to see how items in your kitchen are reaching you through a lockdown

Shampoo sales down, running out of Maggi

At the ‘Home Needs Supermarket’ in Delhi’s Mayur Vihar Phase-1, Arunima, a government school teacher, has been browsing through shelves. She is looking for cocoa powder to bake a cake. “We have run out of cocoa powder,” Rashid, the cashier at the store, informs her, and offers the 34-year-old a bottle of Nutella instead.

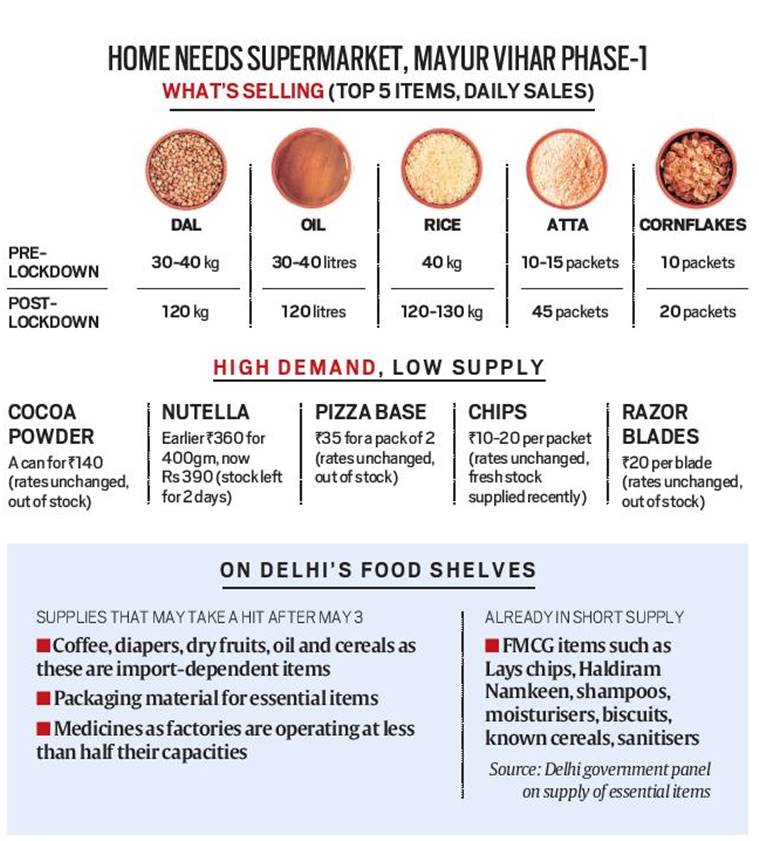

In the past two weeks, since a second lockdown was enforced across the country to check the spread of COVID-19, says owner Sumit Kumar, many of his customers have had to leave disappointed. “There has been a surge in demand for baking products such as vanilla essence, cocoa powder and baking soda, as well as ingredients for making pizzas.

But we ran out of most of these items two weeks ago,” says Kumar.

Established five years ago, the store’s stock of items such as Maggi and chips — also in high demand in lockdown — have dried up too. “We don’t have tissues and toilet paper either. We will run out of sanitary pads in a week,” says Kumar. “With salons shut though, the sale of razors and trimmers has picked up.”

Vegetable vendors like Inder Dev Sah spend hours at mandis to stock up. (Express Photo by Gajendra Yadav/Praveen Khanna)

Vegetable vendors like Inder Dev Sah spend hours at mandis to stock up. (Express Photo by Gajendra Yadav/Praveen Khanna)

On March 2, a 45-year-old businessman in Mayur Vihar, East Delhi, became the Capital’s first COVID-19 case. Since then, there have been 201 cases in East Delhi, and 10 of its areas are containment zones — upsetting the area’s food supply network.

Despite essential industries being allowed to continue operations under the lockdown, grocery stores such as Kumar’s, and several vendors linked to the supply chain, have been facing disruptions in procurement, distribution, and even demand.

While the sale of non-perishable items such as wheat, rice, dal and sugar have increased by 20%, says Kumar, “they have become expensive for us to procure”.

“Earlier, distributors gave us a 2% discount on grocery items, and we would pass on the benefits to customers. Now, there has been a 3% hike in prices. Fortunately, the sale of these products has increased, and people are buying in bulk. Price of cornflakes has increased by Rs 15, but there has been a surge in its demand too,” says Kumar.

However, he says, the demand for otherwise fast-selling daily use products such as shampoo, face cream and deodorant has dropped, and the store has decided not to purchase new stock. “We get more customers now than earlier, but they are only buying a few items. Hand-sanitisers are our fastest-selling product,” he says. Nearly 300 customers visit his store now, compared to 100-200 earlier.

Costs up, sales down for farmers, vegetable vendors

Three kilometres away, in Mayur Vihar’s Yamuna Khadar area, a hailstorm has delayed farmer Chenpal Mandal’s trip to Ghazipur wholesale market. Around 1 am, when it ends, the 42-year-old finds that his coriander and spinach crops spread over five bighas have been destroyed. Left with just a quintal of cucumber now, he packs the produce in a sack, loads it on to a tempo that he has hired for Rs 500, and arrives at Ghazipur market around 2 am.

Most of the vegetables and fruits supplied to grocers in Mayur Vihar are sourced from the 300 shops in Ghazipur market. While the vegetables come here from Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, and Haryana, a considerable portion is also supplied by farms in Delhi — the Yamuna floodplains, Burari and Najafgarh areas.

The Ghazipur mandi opens for business at 10 pm, with trucks, tempos and wooden carts lining up outside through the day. When Mandal arrives at the market, about 50-60 farmers and buyers — without masks or gloves — are already queued up outside each shop, run by a ‘commission agent’. The agents have extra staff to ensure social distancing but their pleas go unheard. Mandal joins the queue, a gamcha around his face.

To avoid overcrowding, the market has replicated the Azadpur mandi system, where three people tested positive for COVID-19 and a 57 year-old trader died. Only 1,000 vehicles are allowed inside at a time, between 6 am and 10 pm, with each batch getting four hours. The wholesalers are allowed between 10 pm and 6 am.

It takes Mandal two hours to sell his cucumber. “Usually, we get Rs 1,000 for a quintal of cucumber. Today, I was paid only Rs 300. Now my family will have to wait another month, when we will harvest spinach,” says Mandal. Along with 15 members of his family, the 42-year-old cultivates onion, spinach, coriander, cucumber, brinjal, radish and cabbage on 16 bighas of land in the Yamuna floodplains.

“Nuksaan ka koi hisab nahin (There is no limit to our losses),” he adds, about the lockdown. “I buy seeds from a seeds market in Laxmi Nagar (in East Delhi). This time, the cabbage seeds alone cost me Rs 60,000. To maintain a bigha, I have to spend Rs 10,000 over three months, and Rs 600 for operating a tractor. I already owe Rs 65,000 to commission agents and farmers,” he says.

In shop after shop at the market, large piles of vegetables lie unsold. At one stall, with tomatoes from UP, Haryana and Bengaluru, the commission agent is selling a kilogram for Rs 5 — down from Rs 12 earlier. Another commission agent nearby is complaining about his unsold bottle gourd. Earlier, a 30 kg sack was sold for Rs 400. He is now willing to give it away for Rs 150.

Read | Central Vista: Nod for new Parliament after nearly 1,300 objections

“The farmers usually hand over their produce to commission agents, who sell it to the highest bidder. Now, if police do not allow people to visit the market, prices will drop. Vegetables start rotting and so are eventually sold at throwaway prices,” says Rajender Sharma, former chairman of the Agricultural Produce Market Committee, Azadpur.

As Mandal begins the 6-km walk back home, with only Rs 300 in his pocket, he worries, “Police peet rahi hai, corona peet raha hai (Both police and coronavirus are hitting us). Who cares for farmers?”

Read | Back-channel used to ‘urge’ Pak to release Kulbhushan Jadhav: Harish Salve

At Bhagyawan Society in Mayur Vihar Phase-1, Inder Dev Sah is among the handful of vendors who has set up his cart on a Tuesday morning. “I have been selling vegetables to the 95 families in this apartment for five years. Today, I woke up at 5 am to go to Ghazipur mandi. It took me two hours to buy vegetables worth Rs 4,000. I crossed three police checkpoints,” he says.

For the next three hours, he does not get any customers. Finally, around 11 am, a retired government officer stops by to purchase peas for Rs 15. Before the lockdown he would make Rs 400-500 every day. “Now it’s Rs 100-150.”

Sah has been asked to leave the spot on several occasions by police. “But I return every day,” he smiles. “My son has a medical condition because of which he can’t walk. I have to work to pay for his medicines.”

Problems in the breadline: manufacturer to godown, shop

SOME distance from his shop, outside the ‘park wala market’ in Mayur Vihar Phase-1, Jitender Dwivedi is shouting into his phone: “Ten crates of brown bread, five crates of milk bread… need it now.”

The 42-year-old delivers bread to shops in the area. “At 5 am, I take my tempo truck to a local godown in Trilokpuri and pick up 50 crates of bread. The godown owner pays me Rs 300 for a day’s work,” he says.

Read | Four security personnel ‘trapped’ in house as J&K encounter on after 8 hours

The bread godown, a kilometre away, operates from a 6×6 ft ground-floor room. Maina Devi (56), the owner, has been in the business for over 30 years, earning around Rs 1,200 a day selling 150 crates to shops in Trilokpuri and Mayur Vihar. “I have two rickshaws, a scooter and a tempo truck for delivery… While our bread supply has not been affected, I am concerned about my delivery boys. They go into areas which may have COVID-19 patients,” says Devi.

She, in turn, sources her bread from a middleman, Mujahid, who buys it from a manufacturing unit in Samaypur Badli.

“Earlier, I used to buy around 3,000 loaves. Now, since the demand is down, I buy 1,500 loaves, paying Rs 7 a loaf. At 8 every night I queue up outside the manufacturing unit and sometimes wait till 2 am. I then deliver the bread to around 15 small godowns in Trilokpuri area,” says Mujahid, 22.

Read | Rush for seats as first train leaves from Surat, site of migrant unrest

While both Devi and Mujahid deny any disruption in bread supply, Dwivedi warns of a shortage.

Industry sources say that with most bread manufacturing units functioning with skeletal crews, and sourcing of raw material becoming tough, production is a challenge. “It takes eight hours to make a packet of bread. It’s a labour-intensive job which involves heating, cooling, moulding, and quality-testing. Furthermore, the raw materials comes from millers based in Haryana and UP, and ensuring drivers for transportation has been challenging,” says a official from Big Basket.

Another official, who looks after bread supply at the online grocery portal, says the disruption is due to many factors.

Read | Arvind Subramanian on Covid response: ‘We should be driven by need’

“For example, packaging. The plastic covers, which are manufactured in Bengaluru, are in short supply. We are even running low on the stock of ink used to print manufacturing dates. How can we send out bread packets without a manufacturing date?” he says.

Hotels shut, poultries see egg sales plunge

Between 6 am and 8 am, 70-year-old Ramjilal delivers 100 crates of eggs to grocery stores in Mayur Vihar Phase-1. “I can earn up to Rs 300 a day. In the past weeks, the supply of eggs has reduced considerably. I also keep getting batches of bad eggs. There are days I don’t make even Rs 100,” he says.

Three km away, in New Ashok Nagar, Ramjilal’s supplier Sitaram lies on a bed with crates of eggs stacked around him.

In a corner, a worker shifts rotten eggs to a crate, while a cashier gives salary to two drivers. These drivers bring Sitaram’s stock of eggs from Haryana’s Panipat every day, which may now be a problem due to the state sealing the border with Delhi.

“I get 1,800 trays of eggs, each with 30 eggs. A tray costs Rs 102. My drivers leave for Panipat at 4.30 am and return around noon. The eggs are then supplied to areas in East Delhi,” says Sitaram. However, he too complains of rotten eggs, “sometimes more than 100 trays”.

At the Panipat poultry farm, owner Raj Kumar is anxious about his debt of Rs 5 lakh. “I have been a poultry farmer for 40 years and own about one lakh chickens. I send out about 80,000 eggs daily. Now I am getting Re 1 for an egg, from Rs 4 earlier… No wholesaler comes. The hotels are shut and the demand is very low,” says Raj Kumar.

Surinder Bhutani, general secretary of the Central Haryana Poultry Farmers’ Association, says transportation hurdles have hit the industry. “There are 2,000 poultry farms in Haryana. Our main customers are in South India. It has become difficult to transport eggs. Even if we get the eggs to the street vendors, their business is shut. In the last one year, the cost of chicken feed has also increased. Then, there is the cost of medicines for them, labour, trays. All poultry farmers have sustained heavy losses.”

Mother Dairy at helm, milk flows smoothly

Apart from the grocery stores that stock milk, most residents of Mayur Vihar depend on the neighbourhood’s 22 Mother Dairy outlets. At one such outlet, Anmol, 27, is making a list of the inventory. Her father has been running the milk booth since 2005. It is 12.30 pm, and the outlet has run out of its high-selling double-toned milk.

“The fresh batch will come only in the evening,” she says, adding that while they had never seen anything like the lockdown, “the supply of milk has remained steady”.

Read | Daily tests up from 4,300 to 75,000 since April 1

This is a fact attested to by most stores and milk booths, unlike in the case of other essential grocery items. “In the early days of the lockdown, there were some issues, but they were sorted out on a daily basis. One main concern was of drivers going hungry while covering longer routes. We have now ensured adequate ration on their journeys,” said a Mother Dairy spokesperson.

The milk at Anmol’s booth is procured from a processing plant in the Patparganj industrial area. The plant gets its supply from 10 states, including Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan, Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh. “The milk is procured through a network of pooling points in villages, where strict quality control is maintained, right from the milking of animals to the processing plants. The milk collected is chilled to below 4 degrees Celsius in our bulk coolers/milk chilling centres to ensure good quality of raw milk during transportation to Delhi,” the spokesperson added.

Read | Finding doctors to certify them fit, obtaining clearances test migrants’ patience

When it arrives in Delhi, the raw milk undergoes a series of tests at various stages of processing. As per Mother Dairy records, 50-55,000 litres of milk is delivered to the 22 Mother Dairy booths and nine milk distributors in Mayur Vihar every day.

Trucks carrying token milk and pouch milk make 24 trips to the neighbourhood every day, and each truck carries between 1,500 and 8,000 litres of milk.

Milk and cheese products at Sumit Kumar’s grocery store are sourced from a distributor based in Patparganj.

In Mayur Vihar, about 90 people, including booth operators, distributors, salesmen and drivers are part of the Mother Dairy supply chain.

At grocery store, now a daily trip to stock up on supplies

Back at the Home Needs Supermarket, Sumit Kumar and his cashier Rashid are waiting for the day’s supply of cold drinks and pulses. Earlier, explains Kumar, distributors would take their order over the phone and deliver the stock to the store. But since the lockdown, with the supply chain disrupted, the burden of transportation has fallen on them.

Amit Kumar, a distributor based in Patparganj, supplies to Kumar’s store Maggi, ketchup, cheese and milk products for infants, procuring the stock from wholesalers in Ludhiana, Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh. “There has been a 50% fall in my stock procurement. Many of my orders from other states have not arrived. Some of the trucks were turned away by police, while some orders could not be delivered due to staff shortage. Last week, I shut down my warehouse following an order by the district magistrate. I was unable to ensure social distancing among my staff. We are trying to deal with these issues to kickstart the supply again,” says Amit Kumar.

So, for now, cashier Rashid heads out on his scooter to distributor godowns in Kondli to get items such as cocoa powder, Maggi, chips, soft drinks and toiletries for the shop, but most of them, he says, have run out of supplies. “I have to go every day, whereas earlier, the stocks sent by distributors would last over 15 days,” he adds.

What has also changed in the lockdown, says Kumar, is that distributors have stopped giving goods on credit. “Earlier, I would pay them after the products were sold. Distributors have even stopped accepting cheques. I have to pay them in cash. This has also driven up prices,” he says.

To avoid a burnout, Kumar recently hired a rickshaw-puller to deliver the supplies in the afternoon. Around 4 pm, the rickshaw-puller arrives, bringing with him 50 bottles of cold drinks and two sacks of dal. Paid Rs 30 for the delivery, he requests a helper at the store for an additional Rs 10.

“Nahin. Abhi naukri hai, isi mein khush raho (No. You should be happy that you at least have a job),” the helper shoots back, going back into the store.