Anastasia Yuferova and Charlie (the cat) on lockdown in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, since March 13. April 29th, 2020. (Image: Sephi Bergerson)

Anastasia Yuferova and Charlie (the cat) on lockdown in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, since March 13. April 29th, 2020. (Image: Sephi Bergerson)

When the coronavirus pandemic spread, forcing countries around the world to come to a screeching halt, Sephi Bergerson, 54, an Israeli commercial photographer who has been based in India since 2002, found himself without any work, like countless others. Dependent on a profession that involves physical presence to develop a symbiotic relationship between himself and the subject he photographs, Bergerson found that he needed to improvise.

That is how the photographer’s latest project ‘Portraits in Lockdown’ came about. Using the FaceTime application on iPhones, Bergerson began photographing people around the world, without leaving his residence in north Goa. “Everyone is at home and we have all the time in the world.” The 10-day-old project, Bergerson explains, was a result of conversations with friends around the world. There was no plan to document times during the coronavirus outbreak.

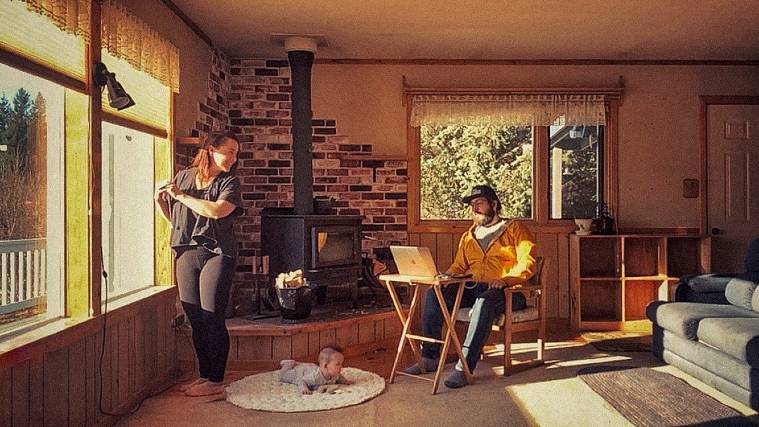

Monica Haim, Arron Kallenberg and Leo Zion Kallenberg. Homer, Alaska, April 29th, 2020. (Image: Sephi Bergerson)

Monica Haim, Arron Kallenberg and Leo Zion Kallenberg. Homer, Alaska, April 29th, 2020. (Image: Sephi Bergerson)

The process of taking portraits using FaceTime isn’t as straightforward as it may seem. It takes some time to make arrangements with people whom Bergerson is going to photograph, as well as a tour around the space in which they live. “I need to see the house and they walk me around it on FaceTime. I tell them to show me the light— the kitchen, the windows, and I decide what the frame looks like.”

Jared and Emmaline Chan at the hotel room in Melbourne. This is their last day in Australia and they will be going into a 14 day quarantine separately upon their arrival in Kuala Lumpur. April 26th, 2020. (Image: Sephi Bergerson)

Jared and Emmaline Chan at the hotel room in Melbourne. This is their last day in Australia and they will be going into a 14 day quarantine separately upon their arrival in Kuala Lumpur. April 26th, 2020. (Image: Sephi Bergerson)

Begerson instructs the subjects where to stand and how to set up the iPhone camera and FaceTime live-videos of 1.5 seconds are taken using a remote camera, all done in a single session. “I shoot while I have a conversation. I tell them I don’t want them to tidy up their home or to dress up. You tend to care less about your appearance during the lockdown,” he says. There is only one instruction for the subjects— for them to come for the shoot as they are. “The less you change for the photo, the more authentic it is.”

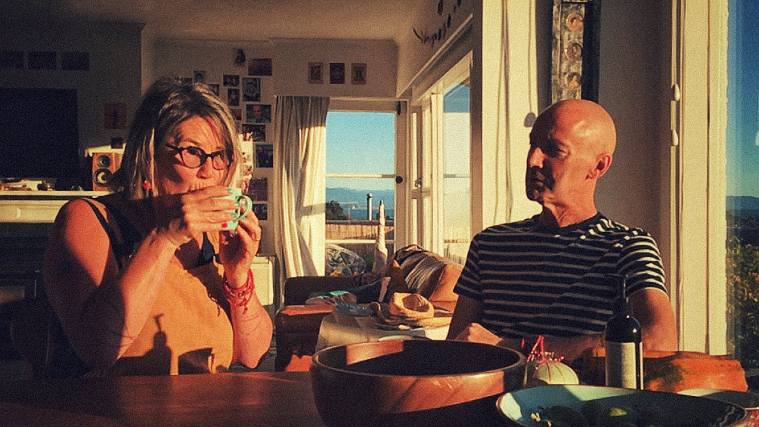

Jolie DeGaia and her husband Ian Gunter at home in Nelson, New Zealand. (Image: Sephi Bergerson)

Jolie DeGaia and her husband Ian Gunter at home in Nelson, New Zealand. (Image: Sephi Bergerson)

The portraits, some available for viewing on Bergerson’s website, are a look into the private spaces of people and how they spend time in a world under lockdown. A motley collection of grainy images of people from around the world, the portraits look very obviously like none of the other high-resolution images that have been taken by Bergerson using digital cameras. But Bergerson says that these FaceTime images aren’t meant to be so.

Angie Ramani- Rohart & Ludovic Rohart on Diani beach, Kenya. (Image: Sephi Bergerson)

Angie Ramani- Rohart & Ludovic Rohart on Diani beach, Kenya. (Image: Sephi Bergerson)

While the first few portraits were a result of referrals and shoots done featuring relatives and friends around the world, Bergerson opened it up to everyone. More recently, people interested in participating in the project have found him on his website and reached out with requests to participate. The photographer is assisted by his wife Shefi Carmi-Bergerson who helps set up initial interviews with the subjects and coordinates other aspects of preparing for the shoot. The subjects used everything from tripods to adhesive tape and empty coffee boxes to set up the iPhones, all under Bergerson’s direction over the phone. According to the photographer, the FaceTime images have been heavily edited in post-production.

Felix Bürkle, Essen, Germany. He spent 14 days in quarantine but is now free to go out. April 19, 2020. (Image: Sephi Bergerson)

Felix Bürkle, Essen, Germany. He spent 14 days in quarantine but is now free to go out. April 19, 2020. (Image: Sephi Bergerson)

Using iPhones to shoot projects is nothing new for the photographer. In 2016, Bergerson ambitiously used only an iPhone 6s Plus to shoot a three-day wedding in India. Over the years, the phone has hence become an important part of Bergerson’s work, where entire projects have been undertaken using only the most upgraded version of the device. “The phone is a working tool. The phone not only became the camera but also the facilitator.”

But the use of the iPhone 11 Pro Max for this project signals a shift in the world of photography for Bergerson as well as in the way he goes about his job. In a post-COVID-19 world, he, like many of his colleagues elsewhere, is experimenting with the craft and what it means for the profession when public health and safety regulations prevent them from travelling and coming in close proximity with others. From a different perspective, it has allowed Bergerson to “travel” to places that he may not have otherwise had access to for photography.

Benny Dayal and Catherine Philipe Dayal in Mumbai, India. April 2020. (Image: Sephi Bergerson)

Benny Dayal and Catherine Philipe Dayal in Mumbai, India. April 2020. (Image: Sephi Bergerson)

As an Israeli passport holder, his citizenship prevents him from travelling to at least 15 countries. Through this project, however, he has been able to access people’s homes and see how they live. His portfolio contains a set of grainy portraits in this ‘Lockdown’ series, in which one photo features a mother and daughter sitting in their home in Dhaka, Bangladesh, a country to which Bergerson is not permitted to travel. An unexpected obstacle that came up in this process was that some countries in the Middle East that Bergerson cannot travel to, for instance Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, and United Arab Emirates, including Dubai, do not permit the use of the FaceTime applications in their territories due to local regulations. For now, Bergerson finds his access to people in these nations completely cut off for the foreseeable future in terms of his project, but hopes to get a diverse range of cities and people into his frame.

Rokeya Quader and her daughter Vidiya Khan. Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Rokeya Quader and her daughter Vidiya Khan. Dhaka, Bangladesh.

In a post-coronavirus world, with widespread travel restrictions for public health and safety and no clarity on when people may be able to travel the way they used to, it may just lead to a rethinking of more ways in which people use technology to get back to their everyday lives, to overcome physical distances, national borders, and in some cases, government regulations.

Sephi Bergerson’s project can be found here