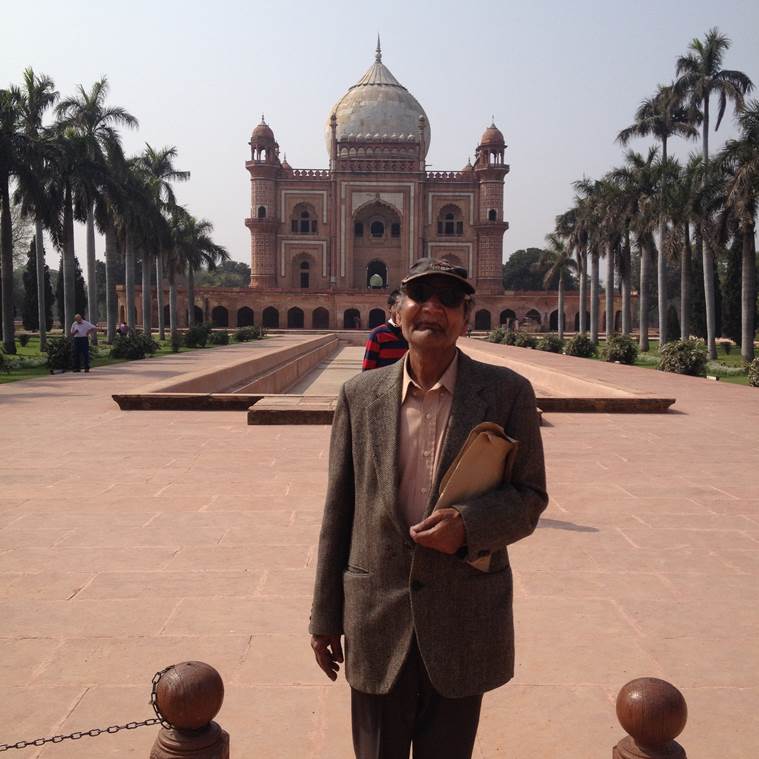

Smith could weave facts and received wisdom with mysteries and gossip to produce a colourful tapestry – with larger-than-life characters and buildings forming the main narrative, interspersed with curiously-placed, jewel-bright cameos. (Photo: Ipshita Banerji)

Smith could weave facts and received wisdom with mysteries and gossip to produce a colourful tapestry – with larger-than-life characters and buildings forming the main narrative, interspersed with curiously-placed, jewel-bright cameos. (Photo: Ipshita Banerji)

Born in an Anglo-Indian family in Agra, Ronald Vivian Smith came to live in Delhi in 1961. And for the next sixty years, Delhi became his dayaar-e shauq, his home of love. When young, he walked its streets and later took to riding buses that took him across the length and breadth of this city. He watched it change and grow from a fledgling capital to a big, bewildering metropolis.

Age and ill-health confined him somewhat to his trans-Yamuna neighbourhood, but Smith sahab’s memories remained alive and alert as ever; they roamed the city, its streets and alleys, its tombs and pavilions, its parks and arcades as freely as his feet once did allowing him to continue to write his columns and to earn his livelihood through the only means he could – through his pen, or to be more precise, his typewriter since he remained, happily, computer illiterate.

In his mind’s eye he could still recall the places he had seen and the people he had met, the food he had tasted and the sights and sounds he had once soaked in; he also had a near-perfect recall of the stories he had once told with such elan and the ones he heard had or even the ones he had heard from those who had, in turn, heard from others before them.

All of this combined to give a piquant charm to his writing. Those who knew him or had spoken to him can vouch for the fact that Smith sahab wrote exactly as he spoke. Like a chatty but prodigiously knowledgeable family elder, he could answer all one’s questions about our city, questions that one didn’t know who else to ask.

Also Read | R V Smith: The raconteur of Delhi, lover of its charms, chronicler of its secrets

For instance, why and how did the saint disappear and why is an observatory (Pir Ghaib) known by his ‘absent presence’? Who was Matka Pir and instead of the usual offerings of flowers and petals, why do devotees offer clay pots (matkas) at his shrine? Who was the Bhure Shah who lies buried in a tomb outside the Red Fort? Who is buried in the exquisite but little-known tomb of Lal Kanwar inside the Golf Club: a dancing girl who became the mistress of Jahandar Shah, or the mother of Shah Alam II? Who was the Jat Hero Suraj Mal? Who was the mysteriously named Bhooli Bhatiyari who has not one but two buildings named after her, that too, situated at a fair distance from each other?

How do monuments acquire the names they do: the Chauburji Masjid that is a hunting lodge and not a mosque yet is called one. Equally well-versed about the city’s Anglo-Indian past, he could be relied to tell you all about ‘masihi shairi’, or tell you what was a Delhi Christmas like in the 1890s. And what of the Bhure Khan, Bade Khan, Kale Khan…. who were they and why did they have the handsomely rugged tombs named after them in the South Extension neighbourhood?

The professional historian has little regard for anecdotes and oral histories and none whatsoever for myths and legends. The Bhure Khans and Bhooli Bhatiyaris would have slipped through the cracks of history were it not for city chroniclers such as Smith sahab. No nugget of information, no whiff of a story was too small or inconsequential for him.

He could weave facts and received wisdom with mysteries and gossip to produce a colourful tapestry — with larger-than-life characters and buildings forming the main narrative but curiously-placed cameos that were small but jewel-bright and minutely detailed. It was this skill of seamlessly placing the ‘big picture’ alongside the ‘small picture’ that was, to my mind, Smith sahab’s greatest skill. Like Jane Austen’s proverbial two-inches of ivory, Smith sahab’s micro-histories add nuance to our understanding of the city that so many of us are happy to call home. Distilled from the city’s heat and dust, its scents and sounds, mixed with dollops of piquant humour and a generous world view, his version of history was, in a word, humane.

Personally speaking, I have always found Smith sahab’s work extremely valuable. I feel no amount of bookish knowledge can compete with the sort of insights and real, lived memories he had. The Delhi he knew at first hand is all but gone, lost irretrievably and hence can never be accessed by the generation of writers who came after him. What is more, he had a fund of anecdotes and qissa-kahanis about Delhi, its people, places and passions. He had enjoyed a long and colourful innings in this city and it showed in his writings.

Evidently, he was a voracious and eclectic reader; what made his writings on Delhi so different from others was his own fund of memories and insights into the city as well as his vast and varied reading. And yet what was most refreshing was that he made no pretense at being a scholar. Perhaps his greatest charm — both as a person and as a writer — was his affableness and humour, and his eye for the offbeat.

Like the archetypal wanderer of yore who walked the city streets, whose self-appointed task was to provide what Honore de Balzac once memorably described as a ‘gastronomy of the eye’, Smith sahab was a constant chronicler. In column after column and essay after essay, he introduced us to sights and sounds not to mention people and places that we would have remained blithely bereft of. I must say I have been an avid reader for years and, each time, found myself charmed by the easy intimacy to his writings about the past.

Like the city flaneurs (the word being derived from the French noun flâneur, means “stroller”, “lounger”, “saunterer”, or “loafer”), Smith sahab’s seemingly aimless ramblings over six decades yielded a rich crop of memories: vivid, colourful, detailed, graphic to the point of photographic recall. The painter with the pen, the urban explorer, the connoisseur of the street, R.V Smith died early this morning and was buried at the Burari Christian cemetery. Untethered from a life that had been difficult for him in the last few years, he is hopefully free to roam the streets of his beloved city whereas we, his friends and admirers, can only mourn his passing.

Filled with regret for not reaching out as often as I should have, I am reminded of these words by Muneer Niazi:

Hamesha deir kar deta huun main har kaam karne mein

Zaruri baat kahni ho koi vaada nibhana ho

Ussey awaaz deni ho ussey wapas bulana ho

Hamesha deir kar deta huun main …

(Jalil is a Delhi-based writer, translator and literary historian)