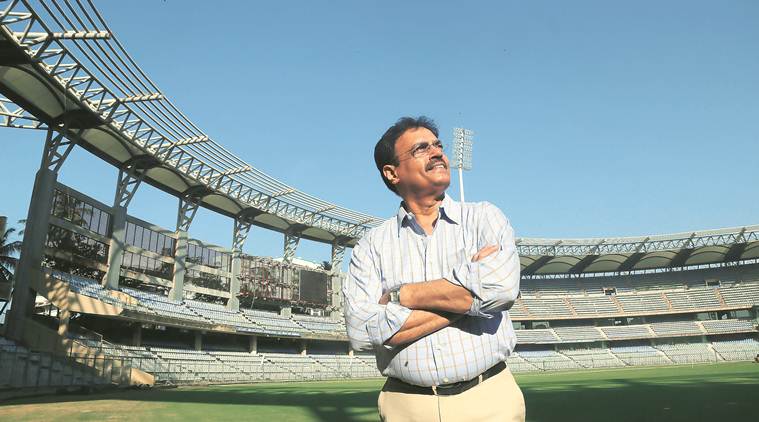

Dilip Vengsarkar scored 103 in 1979, 157 in 1982, and 126* in 1986 at Lord’s. (Source: File Photo)

Dilip Vengsarkar scored 103 in 1979, 157 in 1982, and 126* in 1986 at Lord’s. (Source: File Photo)

Oh, to walk half a mile in Dilip Vengsarkar’s shoes. Especially, the stretch from St. John’s Wood tube station to the time capsule that is Lord’s cricket ground. His first visit was more than 40 years ago, but admirers, lugging their old-school photo albums, still flock around when the only overseas batsman to score three Test centuries there makes the walk.

“I am always surprised whenever I am at Lord’s. The English fans know who’s who. They still believe in autographs and photographs. But they don’t disturb you. They wait for their moment to approach you,” says Vengsarkar. “When I first toured in 1979, everybody had said that you’ll be written about only if you score runs in England. And Lord’s, well, you read so much about the ground, hear so much about it on the commentary that you want to succeed there. More than two centuries old, and the way they care about their history and tradition is unbelievable.”

“Now, just making that walk to the stadium, walking on the greens there, you get goose pimples. It feels like yesterday, yaar.”

Win-win

Never had Vengsarkar been more nervous at the venue than he was during his third England tour in 1986. The previous two visits had yielded two etchings on the Lord’s Honours Board for Vengsarkar, who was batting at 85 when No. 11 Maninder Singh walked in. India were 303/9 and had earned a first-innings lead of nine runs, and Vengsarkar’s mind wavered to the summer before, when he was left stranded at 98 in Sri Lanka.

“That match, Maninder was playing well until he got bowled playing across. It was on my mind, a hundred per cent,” Vengsarkar laughs. “I just reminded him once and Maninder batted extremely well. I got the third hundred but more importantly, we got a good lead.”

The unbeaten 126 set up India’s first win at Lord’s — “I just looked around and felt the happiness on every Indian’s face. They all drank and danced under the balcony, on the ground itself”.

Two weeks later at Headingley, 61 and an unbeaten 102 from Vengsarkar secured a series victory for India.

“I was on top of the Deloitte ratings for 21 months straight,” says Vengsarkar, who finished 1986, his most prolific year, with 793 runs at an average of 132.16 with four centuries. “But these things were always a by-product. Records, centuries, all that will happen. Winning matches were always the most important.”

Cruelly though, Vengsarkar had to witness Indian cricket’s biggest triumph from the sidelines of his favourite haunt. In the heady footage of the 1983 World Cup win, Vengsarkar is relegated to one frame, that of him shaking his head, clapping on the dressing room balcony as Mohinder Amarnath plucks a stump as souvenir.

He had already scored centuries at Lord’s in 1979 and 1982 (Vengsarkar is quick to add a fiery 96 in a tour game against MCC) but an injury inflicted by a Malcolm Marshall snorter kept him out of the final.

“I was injured in the middle of the tour, almost two weeks from the final. I was fit for the match but the Indian team was doing really well. And when the team is in good form and performing, the winning combination always stays. Of course, you feel bad missing out on an iconic game.”

Summer of ’79

Dilip Vengsarkar finished 1986 with 793 runs at an average of 132.16 with four centuries. (Express Photo)

Dilip Vengsarkar finished 1986 with 793 runs at an average of 132.16 with four centuries. (Express Photo)

However, it was not ‘love at first sight’ between Vengsarkar and Lord’s.

After the initial excitement came the intimidating, lonely walk from the pavilion to the centre, which very well could have been half a mile on its own. And as mortifying as a walk to the school principal’s office. It starts from the large door in the corners of the dressing room, through the creaking corridors lined with photographs and member rooms, down the sectioned staircase, across the fabled, uncarpeted long room that doubles as a museum with its paintings and paraphernalia, down the stone steps, between the throng of spectators and onto the hallowed green.

For his first Lord’s innings, a 12-ball duck, Vengsarkar made that to-and-fro at least six times.

“Rain interruptions, but you soon learn that’s no excuse in England. And at Lord’s, if you score a duck, it’s a long way back. So the second time I went in, I was muttering ‘I don’t want to get a pair at Lord’s. That will be a disaster’,” Vengsarkar recalls. “I didn’t want that against my name in the record books.”

He scored 103 in the second innings and, along with Gundappa Vishwanath (113), helped save the Test. He cut, slashed, pulled, glanced, guided, punched. And he drove. And for a fine driver like Vengsarkar, slopes be damned.

“I never thought about that slope,” Vengsarkar says of the famous peculiarity of Lord’s, a two-and-a-half metre drop that runs diagonally across the pitch. “In the later part of my England tours, when I played league cricket (unofficial games played across venues such as West Brom, Sunderland and Chester-le-Street), I came across many grounds with massive slopes. In England, they don’t level the grounds. Headingley too has a slope, it goes the other way, east-west. You could see Bob Willis running uphill.”

READ | The story of Motera stadium

“Players who went in with a positive frame of mind succeeded. At that level, it isn’t like an international bowler will only bring it back in because of the slope. They took it away and you had to adjust,” adds Vengsarkar. “Technically, it is very important in England to stay absolutely side on and play on the off-side. The bowling used to be middle and off to taking it away. If you opened up, you’re gone. You’ll square up, you will edge it to slip. Side on, you got a better view of the ball moving away. I loved to drive, but you had to be very careful of the movement.”

The bowlers were menacing and the conditions more so. Everybody remembers the Bothams, Willises and Pringles but Vengsarkar swears by the miscellany of seamers that made the ball talk in cold English summers.

“Mike Hendrick, John Lever, Graham Dilley. These were all top county bowlers, and our England tours took place in very cold and gloomy conditions. Facing the pace you don’t mind, but the balls wobbled when the English bowlers bowled, you wouldn’t know which way it would go.”

Twin edges

Then there were the lost causes at Lord’s. Vengsarkar singles out two innings when he was squarely in the zone before untimely dismissals stopped his charge.

First was the opening Test of the 1982 tour, the middle piece of his Lord’s trifecta. Following on after the hosts had piled on 433, Vengsarkar scored 157 but says he could have carried on a lot longer.

“I was on the way to score a double hundred, more than that,” recalls Vengsarkar. “We were shot out early in the first innings (128 all out), so we were trying to save the match. It’s all ifs and buts. It was a slow bouncer from (Bob) Willis, edged it and was caught at deep fine leg. That was an enjoyable inning. The wicket was good. Sunshine throughout the day, wicket became a beauty. That one delivery I played badly. Call it complacency, overconfidence.”

Then there was the 1990 tour, Vengsarkar’s last, when the 34-year-old couldn’t make it four in four. The visitors were always playing catch-up after Graham Gooch’s first-innings 333. Centuries from Ravi Shastri and Mohammad Azharuddin raised hopes of a fightback, but Vengsarkar was caught behind at 52.

“I remember I was stroking the ball really well. At 52, there was nobody on the leg side, and it was such a faint nick (against offie Eddie Hemmings). In India, you wouldn’t hear such edges and you could just stay. In cold England, you could hear such nicks from the pavilion. It was very obvious. I scored 35 in the second but we lost.”

In addition to being the only non-English centurion to make the honours board three times — “It’s not like they do it aaram se, in a day or two. Immediately after your innings, your name is there” — Vengsarkar had a tavern suite named after him by MCC in 2001, and six years later his portrait (along with those of Kapil Dev and Bishan Singh Bedi) went up outside the visiting team dressing room.

Lord’s wasn’t the most successful ground for Vengsarkar (four centuries at Feroz Shah Kotla) neither England his favourite opposition (he scored six tons against West Indies). Does he ever get bored of fielding questions about the Lord’s passages?

“Absolutely not,” Vengsarkar says. “You can win many Grand Slams. But people will always go through the list to see how many Wimbledons you’ve won.”