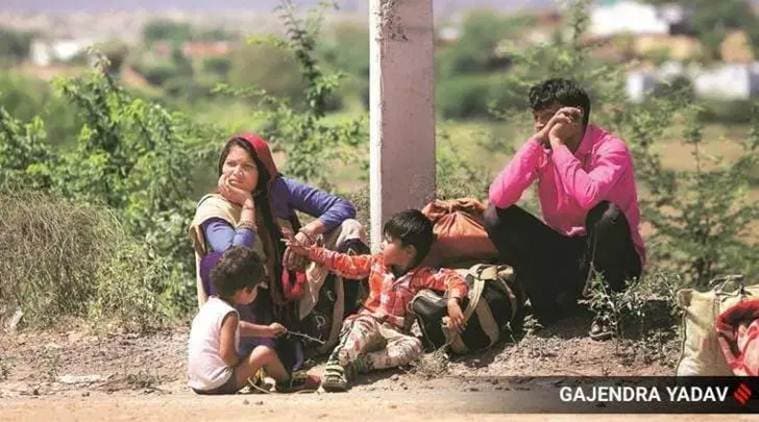

The digital medium has emerged as a powerful passport for millions of citizens to register their expectations from the state and make their voices heard. (Representational)

The digital medium has emerged as a powerful passport for millions of citizens to register their expectations from the state and make their voices heard. (Representational)

It was about 9:30 pm. The phone rang. A well-meaning lady was calling to inform that Sujoy Raj and eight others, all migrant workers from West Bengal, didn’t have any rations left. She had seen the social media coverage of the police’s food-aid initiative and found my number on the district website. She expected the police to help. An hour later, the phone rang again. This time a small uncertain voice spoke at the other end. It was Sujoy, warily telling me that he had been called by the police to his local chowki. I explained to him that all chowkis had been supplied with rations to help those in need. A brief silence followed. He hesitatingly asked, “Mujhe maarenge toh nahin?” A lump rose in my throat at the tragedy of distorted perceptions.

An aware citizen, armed with correct and complete information, had felt it well within her right to assert for the need of others. But a starving man thought of raising the issue of his desperate hunger as a crime. Sujoy did receive rations that night. I hope that we managed to redeem ourselves a little in the eyes of Sujoy and his companions and that the police chowki became a less forbidding place in their mental map.

The difference between the confidence of Sujoy and his self-assured advocate could clearly be attributed to an information divide, fuelled most acutely by the digital divide, particularly in the present scenario.

The digital medium has emerged as a powerful passport for millions of citizens to register their expectations from the state and make their voices heard. The lockdown is witnessing the informed and digitally connected take to Twitter and other platforms to express their concerns about everything — from the urgent requirement of a permit for the last rites of a loved one to the pressing need for a specific baby food customised to their child’s allergies. The authorities respond with alacrity, for social and digital media have evolved as potent barometers to determine the popularity and effectiveness of the state, pinning down the responsibility and accountability of government agencies and gauging their levels of sensitivity and promptness. This is a remarkable empowerment of India’s citizens and the rise of a new proximate relationship between the state and its digitally connected people.

But what about those with no Twitter handles or a platform to highlight a particularly aggravating personal situation? India’s deep digital divide is in ever-sharper focus with most physical means of carrying out business and governance rendered dysfunctional. For instance, most emergency permits being issued by various government authorities are e-passes, which must be applied for and received digitally. As such, the exigencies of the unlettered and the digitally deprived must, by default, languish behind the great divide. We cannot underestimate the disproportionate burden of the lockdown, both psychological and material, being borne by them.

The way to lighten this burden is through an aggressive bridging of the digital divide. A national network of decentralised virtual call centres could be operated in local languages and dialects for the purpose of accessing e-governance. Digitally empowered citizens, remotely serving as “digital volunteers” could be equipped with the relevant helpline numbers, website addresses and URLs for accessing public services. The digitally disconnected could seek help through a simple phone call, which would be queued in the system. A digital volunteer could then connect with the caller in her language, understand her requirement, and initiate the necessary procedures.

Similarly, leveraging India’s vast mobile phone penetration, an artificial intelligence-powered Interactive Voice Response (IVR) mechanism of placing automated calls could be harnessed for proactive dissemination of area-based vital information. Such digital inclusion is essential for the reassurance of India’s teeming millions that the state is in their service and won’t let them languish without an anchor. In this digital age, there is no other way to make every citizen feel like a valued stakeholder than to find a way of connecting them to the power of the digital ethos.

As educated empowered citizens, we must take it upon ourselves to serve as ambassadors of the digitally disconnected. So let us share our awareness. Share our access. Share our Twitter handle for those on the wrong side of the digital divide.

The writer, 31, is an IPS officer serving as DCP in Noida, Uttar Pradesh. Views are personal

This article first appeared in print I Tweet Therefore I’m Heard