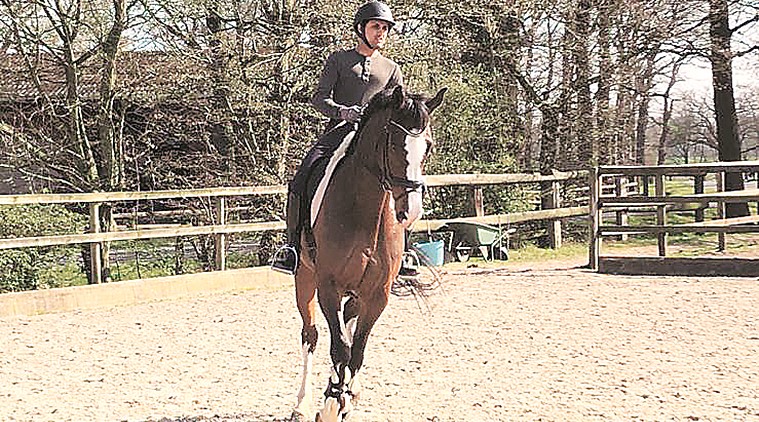

There are 60 horses stabled at the facility where Fouaad Mirza trains. (Source: Express)

There are 60 horses stabled at the facility where Fouaad Mirza trains. (Source: Express)

Far from his home, in a German hamlet, when the world was shutting its borders and people were beginning to lock themselves indoors, Fouaad Mirza was wrestling with a dilemma: whether to return to India to be with his family, or stay put in Germany to take care of his horses.

The equestrian rider hadn’t been home, in Bangalore, for more than a year. This seemed like a good opportunity, given the sporting calendar was wiped out for the foreseeable future. But he also felt responsible for the horses, who relied on him for their everyday routine. “They are like children in many ways,” Mirza says. “You don’t look after them, they won’t survive.”

Not surprisingly, he chose the equines.

Unlike other sportspersons, the Olympics-bound rider says he didn’t have the option of chucking his playing kit to one corner and waiting for things to get better. Horses have to eat every day, go out on the field, exercise and rest.

So, in Bergedorf, a village in Northwest Germany so remote that even the coronavirus hasn’t reached there, Mirza and his four horses – Siegneur Medicott, Touching Wood, Fernhill Facetime and Dajara 4 – continue to live a normal life. “Not more than 100 people live in this village, and most of them are farmers so they are allowed to work,” Mirza says.

“The nearest post office and supermarket are around 8-10km away in a town called Ganderkesee. So we don’t come in contact with many people.”

Still, there are distancing measures enforced. Earlier this month, a tiger in New York became the first animal to test positive for COVID-19, and even though no symptoms were noticed among horses, precautions have been taken.

There are 60 horses stabled at the facility where Mirza trains. Eight of them, which belong to the Embassy International Riding School that backs the Indian, have been kept separately in their own barn.

The training facility has also prohibited the entry of outside horses to ‘restrict the chances of another horse bringing in something’ apart from staggering the work timings. “People who live on the property can work throughout the day. However, those who have their horses here but come from other towns or villages, they have been given specific timings. It’s also made sure that their times do not overlap with ours,” Mirza says.

Following a routine

All this means the 27-year-old’s daily schedule hasn’t changed much since the outbreak of the pandemic. The Asian Games medallist still wakes up at 6am and heads for the stables, roughly 30 metres from his apartment, where his four horses wait for their daily exercise. The only thing that is different now is there are no competitions on the horizon. And even when the shows resume, Mirza predicts the ‘sport will change profoundly’; not in nature but more in terms of the number of big-ticket events that might get cancelled and the horse-rider teams that are likely to be broken.

Recently, the international equestrian federation president Ingmar de Vos told L’Équipe they’ve had to cancel 400 contests because of the virus. “And we do not know when we will be able to start up again. The loss could be €6m or €7m, if the season resumes in July-August,” de Vos added.

Mirza fears the heavy costs involved in maintaining a horse and transporting them for events could further drive the sponsors away in these times of economic distress. That, in turn, could have a bearing on the riders’ careers as well. “In this sport, you’re only as good as your horses. You’ll see a lot of good horses being sold because a lot of a top horses are owned by sponsors and riders are given horses to ride,” he says. “Horses are very valuable, it’s luxury goods for the owners so that’s the first thing they’d like to sell.”

Embassy, he says, have assured him support, which gives him the mental space to keep preparing for the Tokyo Olympics. Next summer, Mirza, who ended India’s 36-year medal drought at the 2018 Asian Games, will become the first Indian since Imtiaz Anees (Sydney, 2000) to compete at the Olympics.

Before that, he will have to navigate through a tricky period when the sport resumes in the post-Corona world, whenever that will be. “I wonder what they might do to restart the shows,” Mirza says. “They might like to possibly test everybody before the show to check they are not carrying the virus.”

A vet performs a health check and conducts a blood test on horses every time before they can leave the country for competition. That, though, is for routine equine diseases. “I don’t know if they have a (coronavirus) test for horses yet,” he says.

At the moment, though, he is enjoying his downtime with the horses, with no pressure of competition.

“You get time to really enjoy the time with the horses. It’s not work, work, work,” he says. “If I had made the decision to go back (to Bangalore), it would have been a bad one.”