Evidence shows that when a crisis leads to school closures, boys return to school but girls often don’t — they just drop out to take care of siblings and do housework until they are married off. (Photo: Getty)

Evidence shows that when a crisis leads to school closures, boys return to school but girls often don’t — they just drop out to take care of siblings and do housework until they are married off. (Photo: Getty)

Written by Manjima Bhattacharjya

In the pre-corona times, I remember returning from a field visit to Jaisalmer feeling hopeful. I’d visited a village where 11 girls were going to join Class IX in a school in the neighbouring district. It was remarkable because no girl from that Rajasthan village had ever studied beyond Class VIII. The local school was only till that level, and it was unthinkable that girls in their teens (considered of “marriageable age”) would be allowed to go so far on their own. There was no public transport, and besides, what if she was sexually harassed? What if she talked to a boy? What would people say?

It had taken the ASHAs (women community health workers) and the NGO staff working locally with them months to convince the parents to let the girls enrol. The girls were to join the school this month. With schools closed because of the COVID-19 lockdown, it won’t happen now. It may never happen now.

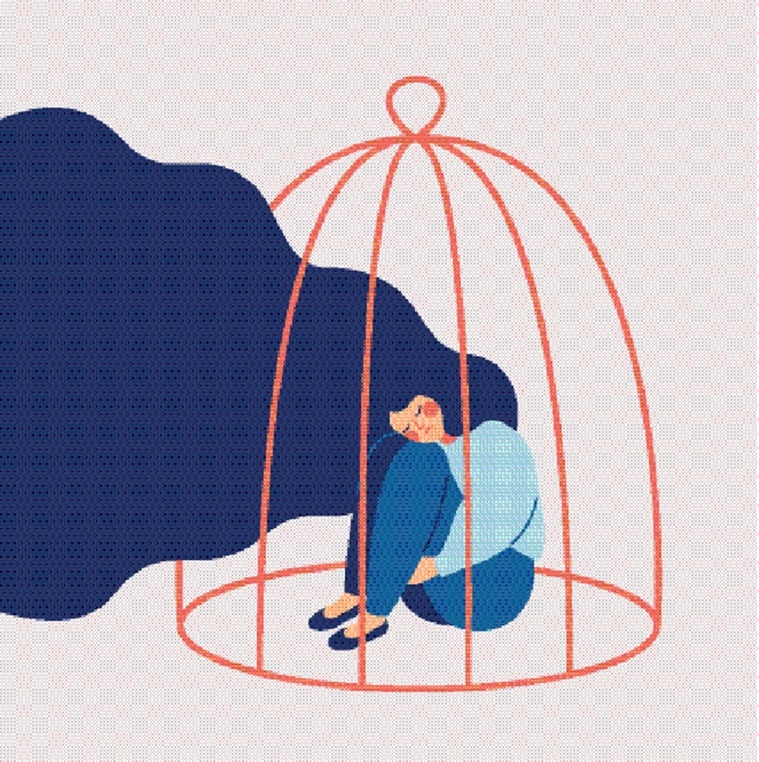

Evidence shows that when a crisis leads to school closures, boys return to school but girls often don’t — they just drop out to take care of siblings and do housework until they are married off. That’s just one of the many ways the lockdown and enforced “stay at home” affects women differently than men.

Staying home is premised on the assumption that a home is a safe place. We know that for one out of three women (at least), it is not. That’s over a billion women and girls and queer people living with violence — physical, sexual, verbal — from partners and parents and others they live with.

Staying home means being nearby 24/7 with their abusers. The UN Secretary-General recently announced “a horrifying global surge in domestic violence” due to the COVID-19 lockdown, saying that in several countries the calls for help had doubled.

In India, however, calls to domestic-violence helplines have dropped. Women’s groups handling these cases are concerned that this is partly because, with the rise in the burden of household and care work falling on them, women don’t have the time to seek counselling for abusive behaviour. Women also don’t have a chance to speak freely into phones (that are often not their private phones) or write emails on the family computer that are now taken over by children doing classes online or playing games.

The switch to online classes that many schools have started has a different implication: India’s digital gender divide is among the worst in the world. If being online is keeping us sane and connected, think of this: despite being the world’s second-largest internet user base and having cheap mobile data prices, only 16 per cent of Indian women use mobile and internet services.

Most women and girls don’t have access to personal devices as men and boys do — often, for the same reasons, the girls in rural Jaisalmer are not allowed to go to school. The fear that it will give them “too much freedom”. In an already unequal and divided society, the move to online-everything will leave millions behind.

Most women and girls don’t have access to personal devices as men and boys do. Only 16 per cent of Indian women use mobile and internet services. (Photo: Getty Images)

Most women and girls don’t have access to personal devices as men and boys do. Only 16 per cent of Indian women use mobile and internet services. (Photo: Getty Images)

This lockdown will sharpen existing inequalities, and relief workers are seeing this every day, keeping a lookout for the especially vulnerable groups — tribal communities, sex workers, single women, female-headed households, those without ration cards, migrants, the homeless. An economic crisis as a result of COVID-19 is in front of us, a rise in unemployment imminent.

When World War II ended, women who had joined the workforce for the first time (because the men were at war) were asked to go back home. Many didn’t. The war had opened a crack in the door for women to enter the thus-far male domain of paid work. In other such moments — India’s independence, Partition, civil wars — women have pushed through cracks to enter the public domain. Even so, we have the alarming statistic of barely 27 per cent of women being in the formal workforce (the world average is 48 per cent).

The lockdown has pushed women back into the private domain. Will it be harder for them to come back out when this is over? Experience tells us that in economic crises it is women who are fired first, and hired last — they’re already a shaky hire because of prejudices around women “needing” maternity leave, the fear of #MeToo, and other excuses companies make to avoid hiring women.

What this means is many women will lose whatever little, precarious, joyous financial independence they had. A woman knows what that feels like. To not have control over spending, not have their “own” money, to quash ambitions. To stay home.

Going out of the house is a hard-fought victory for women. One that women struggle to preserve, being told (by families, communities, the state) that “a woman’s place is in the home” at every opportunity. For many young women and girls across the country — lockdown is their normal. They live under the surveillance of family and society, with limited mobility in the name of “protection”. As adults in colleges in different cities, women are forced by authorities to be back in their rooms by sunset, even as male students are allowed access to the library till late hours at night. This is what has prompted initiatives like the Pinjra Tod campaign in girls’ colleges and hostels; fight the everyday curfews young women face. Welcome to their world. Maybe this experience of the COVID-19 lockdown will make families more empathetic to the captivity of girls and young women in society, and they will be able to step out in the new cautious world with greater freedoms than before.

(Manjima Bhattacharjya is a researcher and writer based in Mumbai)