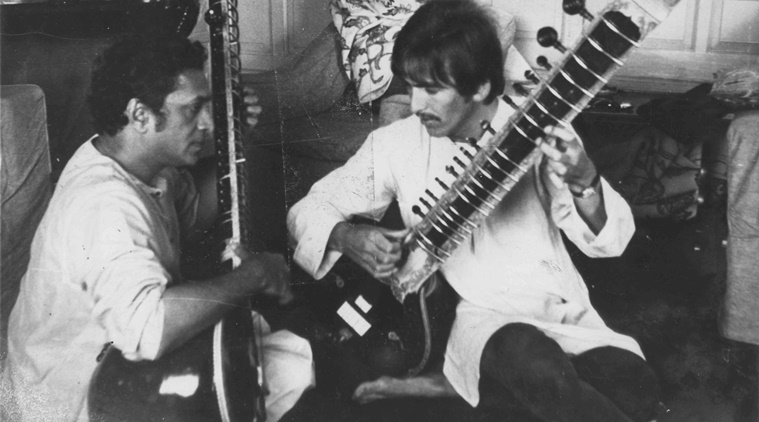

Pandit Ravi Shankar with Beatle George Harrison. (Express Archive Photo)

Pandit Ravi Shankar with Beatle George Harrison. (Express Archive Photo)

On the evening of November 4, 2012, a frail Pandit Ravi Shankar took to the stage at Terrace Theatre in Long Beach, California, a place he had fallen in love with for its moderate temperature and lush spaces. Wearing a nasal cannula, a sandalwood tilak on his forehead, he arrived in a wheelchair. Once seated, he picked up a smaller sitar that had been especially created for him by master sitar maker Rikhi Ram’s grandson, Sanjay Sharma, when he had complained that his older one had become “too heavy to handle”. That evening, he chose to play Pancham se Gara, a raga he created like almost 30 others. After touching each note with tenderness and ending with a tihaai, aided by daughter Anoushka on her sitar, he waved at the audience — who were applauding tirelessly — and broke out in tears. As the applause thundered on, Shankar stood there, held on by his students, tears streaming from his eyes. It was as if he knew that this was the final farewell. He passed away a little over a month later, on December 12. He never contemplated retirement. He was 92.

Grammy-winning cellist Barry Phillips was one of the students who had accompanied Shankar that evening on the bass tanpura. “It remains an extremely sad moment of my life. He loved music, he loved people, he loved giving concerts, he loved life through and through. He gave so much to others in his life. I believe those tears were about all that having to end,” says Phillips. Pandit Ravi Shankar would have turned 100 on April 7.

“It’s been seven years, two months and 16 days exactly. I’ve been counting,” says his wife Sukanya Shankar, 66. “I have had the choice of being completely broken, but I have decided to think that he is still around, and that’s where I get my strength,” she says about an artiste, who, for more than half a century remained India’s greatest cultural ambassador, drafting a blueprint for those who came after him.

Born in 1920 in Banaras as Robindro Shankar Chowdhury, Shankar was the youngest of five brothers in a Bengali Brahmin family. (Photo courtesy: My Music, My Life — Mandala Publishing)

Born in 1920 in Banaras as Robindro Shankar Chowdhury, Shankar was the youngest of five brothers in a Bengali Brahmin family. (Photo courtesy: My Music, My Life — Mandala Publishing)

On April 7, Anoushka, and Phillips along with Shankar’s students from all over the world — Pt Vishwa Mohan Bhatt (mohan veena), Shubhendra Shankar (sitar), Gaurav Mazumdar (sitar), Ashwini Shankar (shehnai) got together and pored over their guru’s another creation, raag Sandhya, and presented it in an almost three-minute presentation. To put together so many threads from so many sounds is a complex matter in Indian classical music. “I couldn’t bear the thought that we wouldn’t be playing any of it tonight, so I asked many of my father’s students to record from their own homes so we could play for you,” wrote Anoushka, who put up the video on her social media platforms. All the concerts around the celebration, including her first-ever concert with half-sister Norah Jones, have now been rescheduled due to the ongoing pandemic.

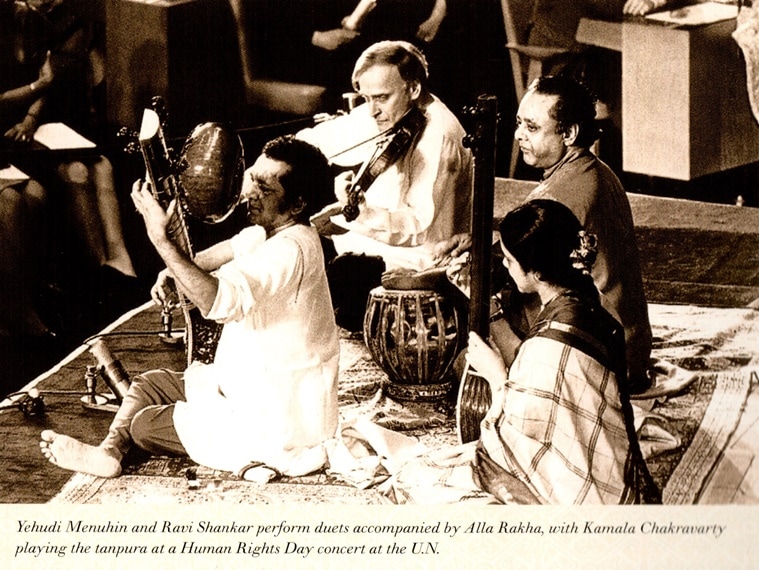

“A maze of noises,” wrote EM Forster in A Passage to India (1924), while describing Indian classical music. Pt Ravi Shankar, whose virtuosity and brilliance would change the way the world understood India and the ingenuity of its music, was yet to burst into the international music scene. Before Shankar, Indian music, for the west, was exotic, monotonous and never considered rich or at par with their classical greats. But Shankar and his corpus of work, according to legendary violinist Yehudi Menuhin, provided “a sense of serene exaltation and how we revere it through the works of Bach, Mozart, Beethoven”. “In him, they (people) recognise a synthesis of the immediacy of expression, the spontaneity, truth and integrity of action suited to the moment, that is a form of honesty characteristic of both — the innocent child and the great artiste. In him they see the mastery and dedication of a discipline born of infinite experience and concentrated effort that are manifestations of not only the artist’s own being but the generations preceding him,” wrote Menuhin about Shankar in the foreword to one of Shankar’s autobiographies My Music, My Life (Mandala Publishing, 2009).

Born in 1920 in Banaras as Robindro Shankar Chowdhury, Shankar was the youngest of five brothers in a Bengali Brahmin family. His father, a Sanskrit scholar and lawyer, was a diwan (minister) in the service of the Maharaja of Jhalawar. He soon left for London to practise law, leaving his family behind. A meagre pension was arranged by the Maharaja for their livelihood. Shankar, a curious child, always had a ear for music. Banaras was full of sights and sounds and a young Robu was in love with it all. A towering figure in his life was his much older brother Uday, who, by then, after studying at the JJ School of Art in Mumbai, had moved to London to study painting at the Royal College of Art. There, in 1923, he met the feted ballerina Anna Pavlova. The meeting led to a collaboration that gave Londoners a glimpse into Indian dance and led to a year-long association between Pavlova and Uday, who was so taken by the experience that he quit painting and became a full-time dancer. He toured with Pavlova’s company, and, later, went on to become a pioneer in modern Indian dance.

Shankar, meanwhile, was learning to sing Rabindranath Tagore’s songs and imbibing the cadences of the river Ganga and the musical incantations of the aarti along its ghats every evening. In 1929, Uday returned, with a dream to tour Europe with an Indian troupe, comprising musicians and dancers. By the fall of 1930, the family was en route Paris by sea. It was in Paris that a young Shankar began tinkering with the esraj, sitar and the tabla. “To me, he (Uday) was a superman, and those days with him did a great deal to not only shape my artistic and creative personality but also to form me as a total human being…,” says Shankar in My Music, My Life. His apprenticeship under Uday in stagecraft, lighting, set design and general showmanship went on to be of great value to him.

For one of these international tours, Uday invited Ustad Alauddin Khan, the sarod player, who was the founder of the Maihar gharana and who he had met in Calcutta at a performance in 1934. The musician agreed to join his troupe in Europe as its music director. It was here that he came across a handsome 14-year-old Shankar, “always chasing girls”. As the legend goes, he told Uday that he would teach the gifted youngster to play “at least one instrument” and to send him to his house. Uday agreed. A few years later, Shankar was sent to Khan in Maihar.

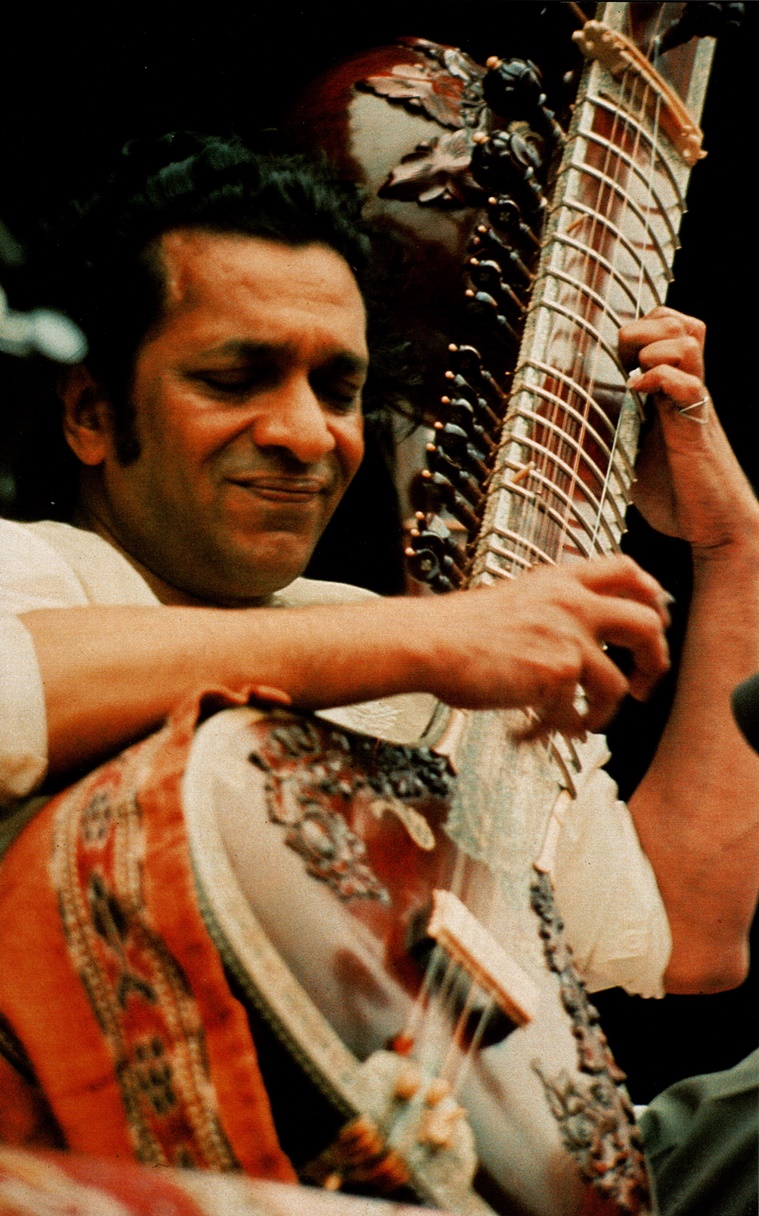

From the dazzling Paris to the austere Maihar was a long journey. The seven-year-long training he received there was to decide the course of Shankar’s life. Every day, at 6 am, he would sit at Khan’s feet, along with his son Ali Akbar, and, sometimes, daughter Annapurna, and learn to coax the sitar into life. It was a tough life for the young man. Khan, fondly called Baba, was a taskmaster. But Shankar understood early on that what he was learning was privileged knowledge; it needed to be imbibed emotionally and intellectually. “You can learn the technique, the speed, but to make each note alive and pulsate with life and feelings so that it can move you, just one sa or one gandhar can bring that particular feeling. This is not something that can be learnt in a year or two. I am strict, orthodox and traditional as far as music goes. The total surrendering to the guru, for whatever vidya, art, technique or craft, this feeling of reverence and respect helps one to learn the sadhana…,” he had said in an All India Radio (AIR) documentary.

Khan had a penchant for crafting individual styles for each of the musicians that he taught. So, he taught Shankar in a certain way. Then there was Shankar’s own personality — charismatic, flamboyant — that added to his style. In 1939, he was ready for his first performance at a conference in Allahabad.

Shankar’s sadhana, meanwhile, had impressed Khan. When Uday suggested an alliance between Shankar and Khan’s daughter, Annapurna, he agreed readily to a Hindu-Muslim marriage — a rarity in those days. The couple had a son, Shubho. The family moved to Mumbai in 1944, with Shankar intending to try his luck in the nascent film industry. They set up home in Malad and began performing at smaller concerts and in music circles in Kolhapur, Pune, Belgaum, Gugali, Aurangabad, Nasik, and Baroda, among others. India was at the cusp of independence and Shankar joined the Indian People’s Theatre Association, where he composed the tune for Iqbal’s famous poem Saare jahan se achha and worked on a ballet project for Indian National Theatre, titled Discovery of India, based on Jawaharlal Nehru’s book of the same name. Nehru was present at its premiere in 1947.

Around the same time Shankar worked as a music composer for two films — Khwaja Ahmad Abbas’s Dharti ke Lal (1946) and Chetan Anand’s Neecha Nagar (1946). A few years later, a family friend, the auteur Satyajit Ray, asked him to compose the music for his film, Pather Panchali (1955). Shankar was so moved by the film that he is said to have composed the score in less than a day. “That was the thing about him. The fact that he could do so much and at an incredible pace,” says Pandit Hariprasad Chaurasia, 81, who was also trying to find his feet as a flute player in the industry. Shankar went on to compose music for the entire Apu Trilogy. Ray was so impressed by Shankar’s work that he created the storyboard of a documentary on Shankar, a project the filmmaker could never finish.

In 1949, Shankar took over as the music director of Vadya Vrind, the radio orchestra at AIR and moved to Delhi, to an apartment on Ferozeshah Road. Classical music was moving out of elitist circles and on to the proscenium stage and the radio. The orchestra had young musicians such as Shiv Kumar Sharma and Chaurasia besides Ustad Alla Rakha on the percussion. It’s during this time that Robindro Shankar Chowdhury became Ravi Shankar. “Ravi Shankar sounded just right, and that was how I told the announcers to introduce me on the radio. All India Radio was heard throughout India, so people came to know me by my new name…I am proud to be a Bengali, but it made me more international, in the Indian sense,” writes Shankar in his autobiography.

Pandit Ravi Shankar at the Human Rights Day concert at the UN. (Photo courtesy: My Music, My Life — Mandala Publishing)

Pandit Ravi Shankar at the Human Rights Day concert at the UN. (Photo courtesy: My Music, My Life — Mandala Publishing)

In Delhi, Shankar came in close contact with businessman and arts impresario Lala Shriram of the Delhi Cloth Mills. The Shriram-Shankarlal family was a patron of the arts and their house on Curzon Road was always brimming with writers, musicians, politicians and philosophers. They often hosted Uday, French dancer Madame Simkie, who performed with Uday, Ustad Allauddin Khan, and, later, Shankar. “In those days, musicians wouldn’t come for a day or two, they would come and spend months,” says Vinay Bharatram, 84, Shriram’s grandson, who learned vocal classical music from Shankar, Annapurna Devi and Ustad Ali Akbar Khan. On one such visit, Alauddin Khan had just tuned in to AIR, when strains of the romantic raga Pilu, being played on the sitar, moved the sarod maestro’s heart. He asked Bharat Ram, Lala Shriram’s son, the name of the musician. Bharat Ram didn’t know, so he sent someone to the radio station to bring the artiste home. A handsome young man walked in. It was Ustad Vilayat Khan. “Baba told him, ‘Tum Enayat (Khan) ke bete ho? Ab tumhare baba toh rahe nahi, par main sikha sakta hoon tumhe,” recalls Vinay, now 84. Vilayat said yes, but never returned. What Khan didn’t know was that a rivalry would soon ensue, between one of his most famous students and this young boy, that would be talked about for years to come.

What Khan didn’t know was that a rivalry would soon ensue between one of his dearest students and this young man, which would be talked about for years to come. It was in 1952, at a concert organised by the family, that this rivalry came to the fore. Vilayat Khan walked into Shankar’s green room and asked him if he could accompany him. Shankar was performing a duet with Ali Akbar, but agreed reluctantly. Khan wasn’t happy. According to Vinay, he “hurled the choicest of abuses” from the audience, that comprised many connoisseurs, including legendary sarod player Ustad Hafiz Ali Khan. Namita Devidayal writes in The Sixth String of Vilayat Khan (2018) that things kept heating up at the concert, each musician going out of his way to better the other. “Maar dala!” exclaimed Haafiz Ali after a particularly enthralling round. Though it was never meant to be a competition, Vilayat had won it.

“Pandit ji (Shankar) would often say that Vilayat Khan’s music is the epitome of shringaar ras. He himself would play from the dhrupad ang. It was meditation of a different kind,” says Vinay, refusing to be drawn into the debate of who was a better artiste. “Everything in my father was the opposite of Pt Ravi Shankar — his music, his dealings with the world. It is exciting to see these two musicians, who were such excellent artistes, doing the same thing but with no resemblance to each other. A rivalry is a good thing. It keeps people on their toes,” says sitar player and Grammy-nominated musician Shujaat Khan, Ut Vilayat Khan’s son.

Singer Mukesh, playback singer Lata Mangeshkar, musician Pandit Ravi Shankar and producer director Trilok Jetly enjoying a joke during rehearsals at the song recording of film GO-DAAN. (Express Archive Photo)

Singer Mukesh, playback singer Lata Mangeshkar, musician Pandit Ravi Shankar and producer director Trilok Jetly enjoying a joke during rehearsals at the song recording of film GO-DAAN. (Express Archive Photo)

There was also Ut Halim Jaffer Khan, the third style, with his famed Jafferkhaani baaj. And also, the inimitable Nikhil Banerjee, a brilliant, warm balance between everything.

Once, at the Berlin airport, an immigration officer looked at Vilayat Khan’s sitar case and asked what was in it. The musician said it was his sitar. The guy said, “one that’s played by Ravi Shankar?” “No, he died five days back,” said an angry Vilayat.

The ’60s was the summer of love in America, with its flower children and their interest in art, spirituality, drugs and the concept of free love. George Harrison, one of the members of the music band The Beatles, decided to learn the sitar from Shankar. Suddenly, Indian music was “the thing”. “I never thought our meeting would cause such an explosion, that Indian music would suddenly appear on the pop scene,” says Shankar in Raga (1971), a documentary on him by Howard Worth.

The association got Shankar two major concerts — Monterey Pop Festival (1967) and Woodstock (1969). Other acts in these festivals included artistes such as The Who, American guitar great Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin and rock giants The Grateful Dead. At the former, while playing Bhimpalasi, Shankar added melodic and rhythmic improvisations to the raga. The audience were spellbound in appreciation. “To have that opportunity, where the biggest pop stars on the planet are saying to all of their fans and the whole world, that listen to this, I don’t think there’s a better PR that you could ever have on this earth for classical music,” says sarod player Alam Khan, Ustad Ali Akbar Khan’s son.

In the coming years, Shankar collaborated with iconic American composer Phillip Glass, Menuhin and famed jazz saxophone player John Coltrane, among others. He was happy with his fame but often wondered if the audience really understood his music. He also started to become uncomfortable with the association of drugs with classical music.

The journey to Woodstock and Monterey required Shankar to make certain tweaks to his music. He shortened his performances, concentrating more on pace. It drew criticism from the purists but enhanced his popularity among his audience. “It’s all about the context. He read his audience and tried to give them what they wanted. His connection to the commercial pop culture scene was unique. That is what shaped the road that he went down,” says sarod player Alam Khan, Ali Akbar Khan’s son. But what Shankar’s popularity in the West really did in the long run was to establish Indian music as a rich tradition to reckon with. It was now on the same pedestal that was reserved for Mozart, Bach and Beethoven.

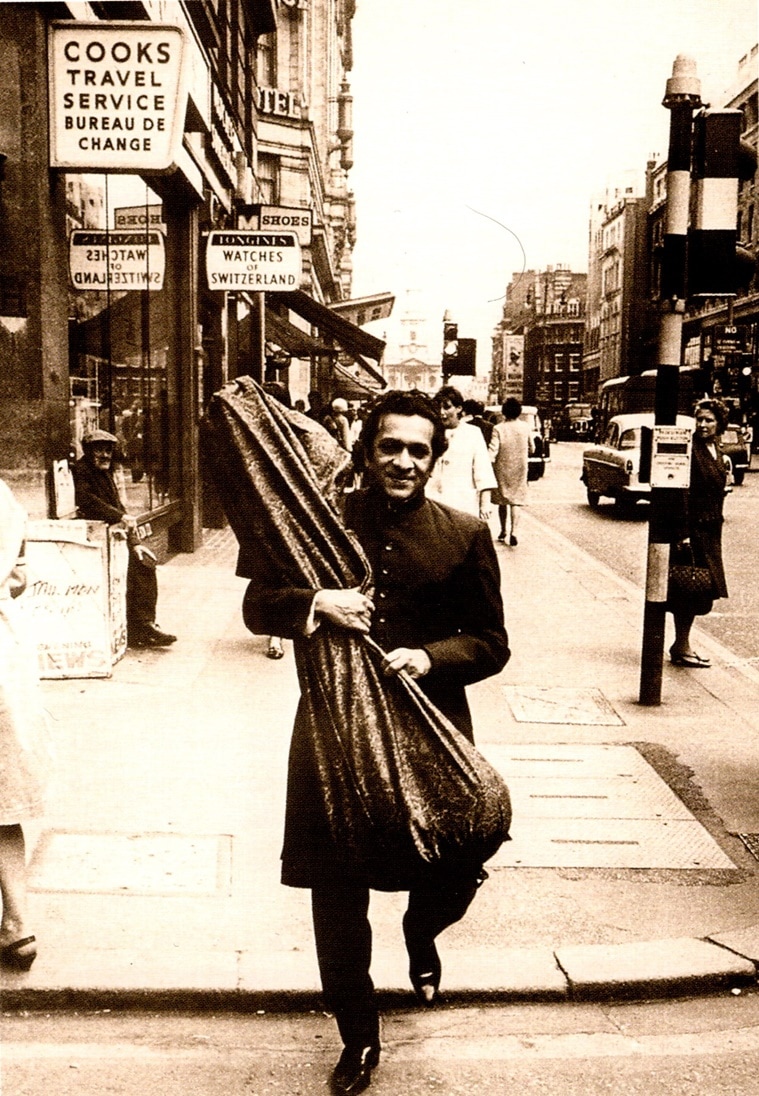

From the dazzling Paris to the austere Maihar was a long journey. (Photo courtesy: My Music, My Life — Mandala Publishing)

From the dazzling Paris to the austere Maihar was a long journey. (Photo courtesy: My Music, My Life — Mandala Publishing)

By this time, Shankar’s marriage with Annapurna Devi was on the rocks. Her meditative music, steeped in her guru’s learnings, was a stark contrast to that of Shankar’s and the two parted ways in the late 50s after her discomfort with Shankar’s relationship with Kamla Shastri, his brother Rajendra’s sister in law. She is seen playing the tanpura in all of Shankar’s concerts abroad in the 50s and 60s. Post this, Shankar would go on to become a superstar, have a slew of relationships, among them with concert promoter, Sue Jones, with whom he lived for about six years. The two had a daughter together in 1979. She was called Geethali, now known as Norah Jones. A relationship with Sukanya Rajan around the same time led to the birth of Anoushka in 1981. Shankar married Sukanya, a London-based banker, in 1989. “People spoke about the many women in his life. I really didn’t care. When he was with me, I was the goddess and nothing else mattered,” says Sukanya.

Shankar would marry Sukanya Rajan, a London-based banker, in 1989. (Photo courtesy: My Music, My Life — Mandala Publishing)

Shankar would marry Sukanya Rajan, a London-based banker, in 1989. (Photo courtesy: My Music, My Life — Mandala Publishing)

In a life so steeped in his art, Shankar’s thirst for music was insatiable till the day he died. His last work, an opera titled Sukanya, was dedicated to his wife of 22 years and partner for 30. He had called upon his longtime friend and collaborator David Murphy, a Welsh conductor, and told him about his vision for it, when he was admitted in Scripps Memorial Hospital in San Diego. “Shankar was very clear about what he wanted to be known as his final piece,” Murphy had said to this reporter in 2017, when the opera premiered at Curve Theatre in Leicester, UK. It went on to be staged at Symphony Hall, Birmingham, and later, at the prestigious Royal Festival Hall in London.

Pandit Ravi Shankar with daughter Anoushka, Norah Jones and wife Sukanya. (Photo courtesy: My Music, My Life — Mandala Publishing)

Pandit Ravi Shankar with daughter Anoushka, Norah Jones and wife Sukanya. (Photo courtesy: My Music, My Life — Mandala Publishing)

“It’s very difficult for a person like myself, who is demanding so much from life and wanting to give so much back. I am so grateful to all of you…I will ask you to bless me, so that till the last day of my life, I can be active and be creative and try to achieve at least half of what I would like to and make all of you very proud of me,” Shankar had said in 1978 in a documentary created by All India Radio. He got what he had asked for — the sitar will forever be remembered as the instrument he made his own.