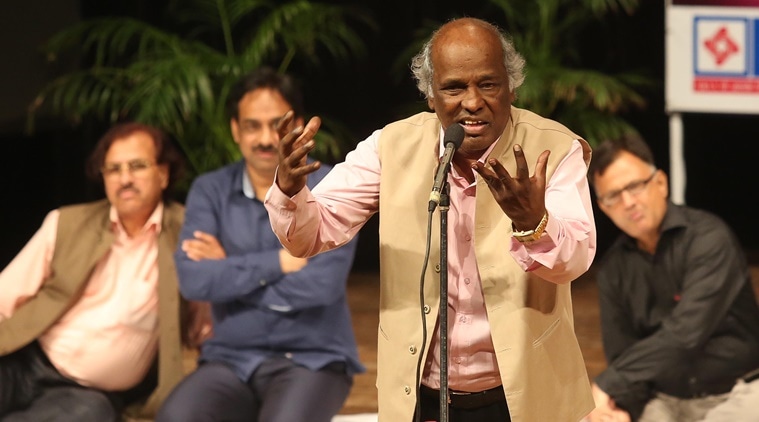

Noted shayar Dr Rahat Indori performing during Jashan E Azadi ‘Kul Hind Mushaira’ at Tagore Theatre in Chandigarh in 2017. (Express Photo by Jasbir Malhi)

Noted shayar Dr Rahat Indori performing during Jashan E Azadi ‘Kul Hind Mushaira’ at Tagore Theatre in Chandigarh in 2017. (Express Photo by Jasbir Malhi)

Subah phir hai wohi maatam dar-o-deewar ke saath

Kitni laashen mere ghar aayengi akhbaar ke saath

(Yet again in the morning, there’s mourning in every nook and corner/ How many corpses will come to my house along with the newspaper)

It was on the morning of March 27 that poet Rahat Indori sat in his home in Indore and penned this couplet. The death toll from COVID 19 had spiked to 919 over a 24-hour period in Italy — the highest number of deaths recorded in a single day since the beginning of the outbreak. Spain’s death toll had just crossed that of China. And back home, in India, people were walking hundreds of kilometres, to get back home, some making it, some letting go of themselves out of hunger and tiredness.

The disconcerting lines, that speak of the vulnerability of life, were a direct response to what he saw happening around him. The coronavirus pandemic had laid bare a shrouded fragility of a system that had, for very long, felt absolute. “Likhne ke alaava, ab chaara bhi koi nahi hai (There is no other way out except to write),” he says in a telephone conversation from Indore. “Ab corona ke zamaane me siyaasi pehlu par kya likhen? Zindagi aur maut par hi likh sakte hain (Now, in times of corona, what political angle should I write about? One can only write on life and death). If his March 27 couplet felt unsettling, Indori’s words on the 21-day-lockdown showed the arrival of more tender poetry from him. Apne ghar mein rakhenge inhe mehmaan ki tarah/ Kuch dino mein humse ghul mil jayenge ikkis din… Unn gareebo ka bhi rakhna hai humein pura khayal/ Jinke yahan hai ye fikr ki kya khayenge ikkis din (We will keep them in our house like our guests/ In some days these 21 days will mingle with us/ We have to also look after the poor/ Ones who are worried what they’ll eat in these 21 days). The piece came to him as he stared at the walls of his house, which had been turned into a canvas by his young grandchildren. “I have been so busy travelling that I had never seen those lines this carefully,” says Indori.

“April is the cruellest month,” begins TS Elliot’s The Waste Land. Why did the greatest poet of our times feel uncomfortable with a month that’s synonymous with spring in many parts of the world? Because, the time of the year that usually is beautiful, romantic, to him is only a stark reminiscence of what once was. It merges memory and desire. Elliot’s early 19th-century poem is also a reminder of today’s reality.

Veteran lyricist and writer Gulzar arrives to pay his last respects to actor Shashi Kapoor at Prithvi theatre in Mumbai. (Express Photo by Vignesh Krishnamoorthy)

Veteran lyricist and writer Gulzar arrives to pay his last respects to actor Shashi Kapoor at Prithvi theatre in Mumbai. (Express Photo by Vignesh Krishnamoorthy)

A plethora of poets around the world are writing at this time, in some ways documenting a crisis and finding new meanings and adjectives for life, death and everything in between. Then there is the matter of what it feels to have been confined in one’s homes. When California-based church minister Lynn Ungar watched the world around her understand the concept of social distancing on March 11, she began writing with a germ of an idea — “the question of how do we become closer through becoming more distant”. She wrote, Know that our lives/ are in one another’s hands/ Do not reach out your hands/ Reach out your heart/ Reach out your words/Reach out all the tendrils/ of compassion that move, invisibly, where we cannot touch. The poem went viral on social media. “I wanted to suggest that staying away from one another didn’t only have to mean that we were less connected, but that it was, in itself, a loving choice that acknowledged our responsibility to one another,” wrote Ungar in an email to The Indian Express. She is a minister with the Church of the Larger Fellowship, which is an online congregation and strongly believes that arts are crucial in these times. “Fear and isolation can bring out the worst in us, including the feeling that since there must be an enemy to fight, some other group of people must be the enemy. The arts remind us that we can respond to stress with creativity, adapting to changing circumstances and remembering that we all do better when we remember the ways we are connected to one another and to our sources of inspiration,” she writes.

Lynn Ungar

Lynn Ungar

Famed writer-director Gulzar’s verses deal with time and the current way of life. Waqt rehta nahi kahin tikk kar, Iski aadat bhi aadmi si hai/ Aap ruk jayiye, ye waqt bhi nikal jayega… (Time doesn’t stay in one place, its habits are like that of a man/ You come to a halt, the time will also pass).

A few days ago, actor Amitabh Bachchan had also made a video reciting his Bhojpuri poem on coronavirus. He attempted to speak about various precautionary measures one should take to stay safe. While lyricist and adman Prasoon Joshi recited his chant-styled Haan ghar mein rahega desh…(Yes the country will stay at home), actor Ayushmann Khurrana spoke of concepts of charity and gratitude in a poem he recited in a home video in his balcony.

Journalist Kuldeep Mishra

Journalist Kuldeep Mishra

But amid many, what managed to find space in the most obscure nooks of the heart was poet and journalist Kuldeep Mishra’s evocative and poignant piece, Ye Hindustan hai aur yeh March ka mahina hai, aur ek faisla aapko karna hai. His piece was a reality check that was wrapped in hope and desire in about six minutes. Vasant koi train ya plane mein baith kar nahi aata/ Wo chala aayega aapke band pade gharon ki khuli khidkiyon se/ Kuchh din ghar mein rahiye jahan apne rehte hain/ Issi bahane fursaton ko jee leejiye… (Spring does not come sitting on a train or plane/ It will come in through the windows of your closed homes/ For a few days stay in the home where our own live/ It will help you find an excuse to live the free time…) It concludes with Dar hai toh ho, par nafrat na ho/ qaid hai toh ho par akelapan na ho/ shaq hai toh ho swarth ki jagah na ho/ beemari hai toh hogi apni jagah, aatma beemar na ho. This was honest, organic and intelligent at the same time. There was science and spirituality in the same breath. “I wrote exactly what I saw around me. But what backs a piece is what one has read in life and understood.

That definitely enters the poetic crevices,” says Mishra. The recitation of the piece was taken by Kathak dancer Mrinalini, who performed it in her apartment corridor, with much poise. A line in his poem, Yahudiyon ke tajurbe padho jahan ummeed ka ek kan na deekhta tha, came from knowing Austrian neurologist, psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl’s famed book Man’s Search for Meaning.

Indori feels that one needs to know of one’s death and the one from Covid 19 is preventable. “This calamity, which has come from the skies, has been felt by the entire world. Ab kamsekam apni maut se aankhen toh milaani hain na? Isliye dehleez ke bahar na jaayen. (At least, death needs to be looked in the eye, right? Therefore, do not step out),” says Indori.