BENGALURU: Like all big cities in the world, it’s no secret that Bengaluru was built by migrant workers. But notwithstanding their contribution to the city’s development — often without minimum wages — they remain invisible. Reason: Most governments have no data on migrant workers, resulting in non-implementation of laws that guarantee their rights.

However, the Covid-19 crisis, which has hit migrants very hard, rendering them jobless and homeless, has thrown up an unexpected result. The government is now scampering to collect information about them and making efforts to provide relief.

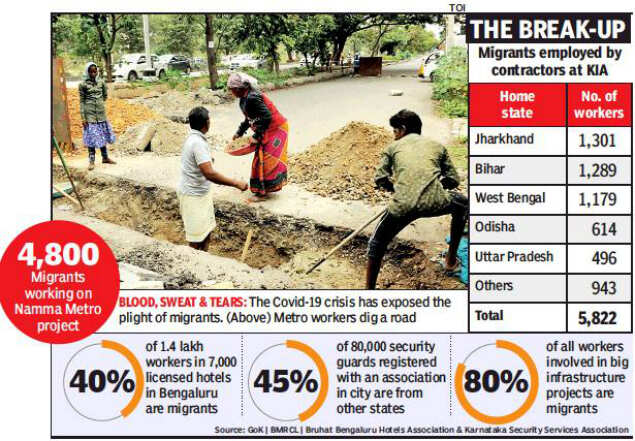

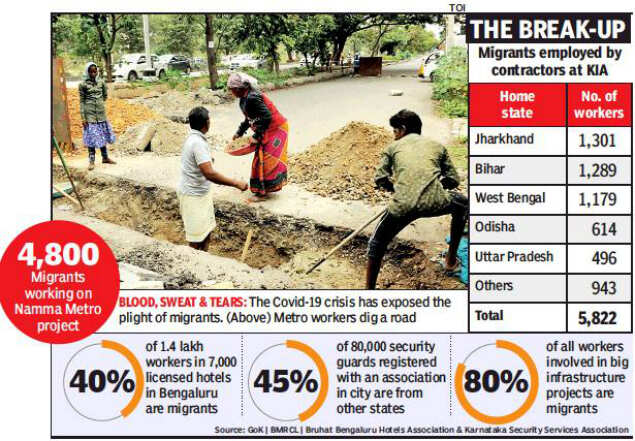

One such report submitted by various contractors implementing the Kempegowda International Airport (KIA) expansion project has been accessed by TOI. It shows there are nearly 6,000 migrants working on the second terminal (T2) and other related projects at KIA.

Advocate Clifton Rozario, who works closely with several workers’ unions and labourers, said: “It’s unfortunate that it took a pandemic to realise the social reality of migrant workers. They are all around us — domestic workers, construction workers, security guards, migrants from the northeast working in the hospitality industry, and so on. But most administrations and cities don’t give them their due.”

KIA, one of the fastest growing airports in India, handled 33.7 million passengers in 2019, compared to the previous year’s 32.3 million. It’s people from Jharkhand, Bihar, West Bengal, Odisha and Uttar Pradesh that make up most of its workforce. According to the data with TOI, at least 5,822 people from these states and a few others have been employed by contractors like L&T, AIC Infrastructure Private Limited, Starworth Infra, URCC, BICPL and others. A majority of them are from Jharkhand, followed by Bihar (see graphic).

“If Bengaluru is booming today it is because of the contribution of migrant workers. But many contractors have fled, leaving workers in the lurch. The government doesn’t know all the places where workers live, and our lax compliance of the law and neglect of these workers as fellow human beings has led us to where we are,” said Vinay Sreenivas from the Alternate Law Forum.

All of the city’s major infrastructure projects have migrant workers — both intrastate and interstate — as their backbone. Namma Metro has about 4,800 migrants going by official figures, but activists like Ekta M from Maraa estimate the number is much higher. Maraa will bring out a report on Metro workers later this week.

NP Samy, general secretary, National Centre for Labour, while pointing out that the state government has been implementing mega infrastructure projects to transform Bengaluru, said: “But it has not taken appropriate steps to register all the workers involved in large infrastructure projects with the Karnataka Building And Other Construction Workers Welfare Board.”

Needed: Better facilities

Sreenivas and Rozario argue that the government should implement the Interstate Migrant Workmen (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) Act, 1979, which mandates registration of establishments employing them, besides making it a must for them to have access to housing, adequate allowances and other facilities. “If the labour department had paid attention to violations of this Act and registration was done, we wouldn't be in this position today,” Sreenivas said, pointing to the Covid-19 crisis.

Sathya Mukund of AITUC argues that failure of the government to register all migrant workers has allowed many contractors, especially smaller ones, to exploit workers. “They are seen in makeshift tents across the city while laws mandate that they get living quarters and other allowances...,” he said.

However, the Covid-19 crisis, which has hit migrants very hard, rendering them jobless and homeless, has thrown up an unexpected result. The government is now scampering to collect information about them and making efforts to provide relief.

One such report submitted by various contractors implementing the Kempegowda International Airport (KIA) expansion project has been accessed by TOI. It shows there are nearly 6,000 migrants working on the second terminal (T2) and other related projects at KIA.

Advocate Clifton Rozario, who works closely with several workers’ unions and labourers, said: “It’s unfortunate that it took a pandemic to realise the social reality of migrant workers. They are all around us — domestic workers, construction workers, security guards, migrants from the northeast working in the hospitality industry, and so on. But most administrations and cities don’t give them their due.”

KIA, one of the fastest growing airports in India, handled 33.7 million passengers in 2019, compared to the previous year’s 32.3 million. It’s people from Jharkhand, Bihar, West Bengal, Odisha and Uttar Pradesh that make up most of its workforce. According to the data with TOI, at least 5,822 people from these states and a few others have been employed by contractors like L&T, AIC Infrastructure Private Limited, Starworth Infra, URCC, BICPL and others. A majority of them are from Jharkhand, followed by Bihar (see graphic).

“If Bengaluru is booming today it is because of the contribution of migrant workers. But many contractors have fled, leaving workers in the lurch. The government doesn’t know all the places where workers live, and our lax compliance of the law and neglect of these workers as fellow human beings has led us to where we are,” said Vinay Sreenivas from the Alternate Law Forum.

All of the city’s major infrastructure projects have migrant workers — both intrastate and interstate — as their backbone. Namma Metro has about 4,800 migrants going by official figures, but activists like Ekta M from Maraa estimate the number is much higher. Maraa will bring out a report on Metro workers later this week.

NP Samy, general secretary, National Centre for Labour, while pointing out that the state government has been implementing mega infrastructure projects to transform Bengaluru, said: “But it has not taken appropriate steps to register all the workers involved in large infrastructure projects with the Karnataka Building And Other Construction Workers Welfare Board.”

Needed: Better facilities

Sreenivas and Rozario argue that the government should implement the Interstate Migrant Workmen (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) Act, 1979, which mandates registration of establishments employing them, besides making it a must for them to have access to housing, adequate allowances and other facilities. “If the labour department had paid attention to violations of this Act and registration was done, we wouldn't be in this position today,” Sreenivas said, pointing to the Covid-19 crisis.

Sathya Mukund of AITUC argues that failure of the government to register all migrant workers has allowed many contractors, especially smaller ones, to exploit workers. “They are seen in makeshift tents across the city while laws mandate that they get living quarters and other allowances...,” he said.

Coronavirus outbreak

Trending Topics

LATEST VIDEOS

City

Delhi Health Minister meets 82-year-old cured COVID-19 patient

Delhi Health Minister meets 82-year-old cured COVID-19 patient  Centre considering states' request to extend lockdown: Sources

Centre considering states' request to extend lockdown: Sources  COVID-19: Ranchi admin bans movement of persons, vehicles after 2 novel coronavirus cases reported

COVID-19: Ranchi admin bans movement of persons, vehicles after 2 novel coronavirus cases reported  COVID-19: Educational institutions will be closed till Apr 30 in state, says Meghalaya Deputy CM

COVID-19: Educational institutions will be closed till Apr 30 in state, says Meghalaya Deputy CM

More from TOI

Navbharat Times

Featured Today in Travel

Get the app