The Jamaat is amorphous — anyone can associate with it for as long as they wish. (Express File Photo)

The Jamaat is amorphous — anyone can associate with it for as long as they wish. (Express File Photo)

The Tablighi Jamaat has been around for 94 years, born in India but today spread across different continents. Lakhs of people are associated with it. Yet, till about a week ago, few outside the Muslim world had heard of it, and the Jamaat did not concern itself much with affairs beyond its stated mission.

Now, as the coronavirus pandemic explodes in India with the Tablighi Jamaat as its startled centre, those associated with it say there is more to the body than the “oversight”, “irresponsible act”, and “pure bad luck” of falling victim to, and spreading, COVID-19.

“What happened at Nizamuddin Markaz is unfortunate and irresponsible. There is no getting away from that. But the kind of spin social media, and sections of news media, are giving to this is distasteful. The Tablighi Jamaat is not some shadowy, secret get-together of “radicals”. Its aim is to make Muslims the best possible version of themselves – true to their faith, contributing to the society, of help to their fellowmen,” says a 42-year-old employee of a New Delhi private firm, not wishing to be named.

Follow LIVE updates on coronavirus pandemic

So who can join the Tablighi Jamaat?

Anyone. There is no formal joining.

Buses head from Nizamuddin West to quarantine facilities in Delhi on Tuesday afternoon. (Express file photo by Praveen Khanna)

Buses head from Nizamuddin West to quarantine facilities in Delhi on Tuesday afternoon. (Express file photo by Praveen Khanna)

“It’s not, say, the Communist Party, where you get a membership card and say “laal salaam”. It’s also not an order of monks,” says Sakib Zaya, a 22-year-old from Bihar studying in a Greater Noida college. “Jamaat volunteers come from all walks of life. They gather to read and discuss the Quran and other religious books, enrich their knowledge, and spread this knowledge.”

The Jamaat is amorphous — anyone can associate with it for as long as they wish. Some simply attend sessions. Some embark together on trips of three days, 10 days (ashra), 40 days (chilla) or 120 days. No ID proofs are sought for these trips, but people know each other locally, so there is a level of community verification.

What is a typical day for a Jamaat volunteer?

In the morning, after the namaaz, every Jamaat gathers together and decides their plan for the next 24 hours.

“This is a democratic process where everyone gives suggestions. The group elects an ameer (leader) from among themselves, generally a senior, learned member. Work is divided, some cook, some go out to meet other Muslims. But basically the three parts of the day are – readings and discussions on the Prophet’s life, inviting the local Muslim community to join our sessions, then a discussion or lecture on the Quran and the best way to practise Islam,” says Hasnain Beg, a PhD scholar at New Delhi’s Jamia Millia Islamia university. “In cities, the outreach visits can happen in the evenings. In villages, where people sleep early, they are done in the afternoon.”

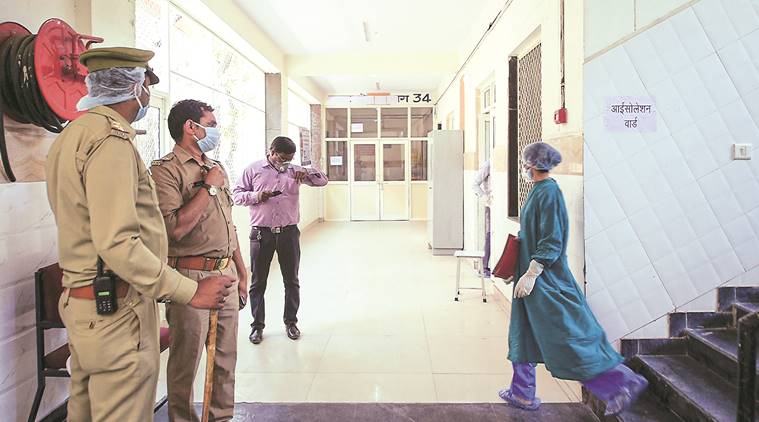

At Ghaziabad hospital where some who were at the Markaz are admitted. (PTI)

At Ghaziabad hospital where some who were at the Markaz are admitted. (PTI)

“The Jamaat believes in six principles – Kalimah (faith in Allah); Namaaz (prayer); Ilm and Zikr (education about and remembrance of God); Ikram-e-Muslim (service of humanity); Ikhlas-e-Niyat (purity of intention); and Dawat-e- Ilallah (call people towards God),” adds Beg.

The Jamaats generally stay in mosques. There are common meals. Every member pays their expenses. “You best learn lessons on which you spend your own time and dime,” says Beg.

What does the Tablighi Jamaat wish to teach Muslims?

The common answer is – to take Muslims closer to the Prophet’s teachings, in letter and spirit.

But does this emphasis on religious education take people away from their worldly duties?

Waseem Ahmed Siddiqui, a Nizamuddin resident who runs a travel agency, says not. “The Prophet’s teachings are as much a guide to everyday life as to spirituality. For example, being a good Muslim entails being sincere in your profession, or you will have to answer to Allah why you did not give your job your best. It involves helping your wife with housework, because the Prophet did that and preached that. It means giving your daughter her fair share in your property. These are the kinds of habits the Tabligh volunteers try to inculcate in themselves and in others.”

An assistant professor in a reputable New Delhi university, not wishing to be named, gives an example. “Once, a group of students was to leave for a Jamaat. College vacations were from Tuesday. Most students had decided to mass-bunk Monday and start the vacation from the weekend. But the Jamaat guys were clear — they wouldn’t embark on the journey by bunking class. They would leave only on Tuesday. Similarly, if you stay away from your job to be involved in Jamaat activities, you are not being a good Muslim. You are not supposed to break any contract, neglect any duties.”

SDMC workers deployed a drone to sanitise out-of-reach areas in Nizamuddin, such as building tops and congested lanes. (Express photo by Tashi Tobgyal)

SDMC workers deployed a drone to sanitise out-of-reach areas in Nizamuddin, such as building tops and congested lanes. (Express photo by Tashi Tobgyal)

Zaya, the 22-year-old student, says: “From the correct way to drink water to how to behave with your elders, there is guidance on everything.”

And what is the correct way to drink water? “With your head covered, taking God’s name, sitting down, and in slow measured breaths instead of one great gulp.”

But is it always possible to cover one’s head while having water?

“Oh, there’s flexibility. The Quran says if you are starving, you can eat even prohibited food. The idea is to follow as much as you reasonably can in your circumstances,” Zaya says.

How is the teaching done?

Leading by example. The college professor gives the metaphor of a lamp. “Your own life should be so luminously upright that people wish to emulate it. There is no question of force or trying to regimentalise someone else. If you do that, people will revert to their ways the moment there is no supervision. But just like one lamp can light a hundred, one virtuous life can inspire many others.”

Once people show an interest in learning, they must not be made to feel inferior, says Siddiqui. “You have to be respectful to the newcomer. Often, even senior citizens don’t know the correct way to offer namaaz. Calling out can embarrass them. So you invite them to “please take a look” at your namaaz. They learn the right way, without being made to feel foolish.”

“Say 12 Jamaatis are travelling in a bus and the conductor deducts money for only 10. So when you reach your destination, you buy two extra tickets. The idea is that the transport body should get its due,” says the professor, giving an example of the principles the Jamaatis are supposed to follow.

Why do some Muslims consider them ‘backward’?

The general consensus is “because of a lack of awareness”.

The Tablighi Jamaat has been around for 94 years, born in India but today spread across different continents. (Express File Photo)

The Tablighi Jamaat has been around for 94 years, born in India but today spread across different continents. (Express File Photo)

“When we say let’s return to the ways of the Prophet, we mean adopt the best practices of going about life,” says Beg, the PhD scholar. “For example, the concept of a dastarkhwan is that often, where tables are not available, people eat on the floor. The dastarkhwan ensures food falls on one cloth or paper that can later be gathered up, instead of dirtying the ground. But no one is asking anyone to swear off table-chairs.”

Most of them had a common query: “Yes, wearing kurta-shalwar and sporting a beard is encouraged. But don’t Sikhs keep a beard and a turban? Don’t Jews wear skullcaps, or Hindu women the sindoor?”

“I would say if you form your opinions about someone based on the clothes they wear, it’s your narrow-mindedness. One can wear a kurta-shalwar and be a nuclear scientist,” says Beg.

“Tablighis are inward-looking, focussed on the deen, yes. But that doesn’t mean they reject contemporary realities,” says the professor. “There were no trains during the Prophet’s time, but we do use trains and planes.”

What of the claims of Jamaatis keeping women at an arm’s length? “I have been talking to you for an hour, haven’t I? You can talk to anyone you need to talk to. The idea is to discourage unnecessary chatter with women who are not your immediate family,” says Beg. “Women participate in Jamaats too,” adds Siddiqui.

After Delhi Police FIR, ED considers probing Tabligh financial dealings

What of the recent Nizamuddin row?

“There are several complaints. What is this proselytisation claim? Jamaatis aren’t trying to convert anyone. They are trying to bring believers closer to the faith. Second, no one gathered at the markaz in one focussed exercise. There is always a 1,000-strong floating population at the Banglewaali mosque, people coming and going, or just passing through,” they said.

Drones being used to sanitise parts of Nizamuddin, New Delhi, on Thursday. (Express photo: Tashi Tobgyal)

Drones being used to sanitise parts of Nizamuddin, New Delhi, on Thursday. (Express photo: Tashi Tobgyal)

Yes, the COVID-19 spread is deeply distressing, they agree. “It was definitely an oversight. The managers at markaz should have had it emptied when the first rumbles of coronavirus were heard. They are so intent on their mission they failed to register what was happening around them,” says the professor. The private firm professional agrees.

Beg, Zaya and Siddiqui point out that the authorities did try to send people out once coronavirus restrictions were imposed, but were prevented by the lockdown. Also, many had gone to other states much before the lockdown was talked about, they say.

All five agree that the media “witch-hunt” is “exaggerated and motivated”. “Doctored, fake videos are being circulated. Whom do they benefit? There is one of Maulana Saad telling people it’s good to die in a mosque. But from what I know, this speech was made after the lockdown. People were panicky and afraid of dying. He was trying to reassure them by saying life is in Allah’s hands and if death must come, a mosque is a good place to die,” says Siddiqui.

What of the allegations of harassing nurses on some Jamaaat members?

The consensus is that it is “extremely unlikely”, the “exact opposite of what the Tablighi Jamaat stands for”. But if the charges are proven, “the guilty must face the law and later answer to Allah”.

“The Markaz authorities should be punished for their irresponsibility, for the loss of life — of Muslims and of others — it has caused. But the glee and consummate ease with which some fell to Muslim-bashing after this is worrisome. This blind hatred, too, claims lives. Who should be punished for that?” says the private firm professional.