Express photo by Shuaib Masoodi

Express photo by Shuaib Masoodi

The lobby had been appropriated. Writers sat on sofas, talking. Any reminder of the purpose of their visit was met with resentment. Indian musicians hate sharing their repertoire with students. They eke out what they know with reluctance. It looked like the writers were no different. They were content to be “Indian writers” as if the category were a caste. They appeared — the word is emphasised as a caveat against taking appearances at face-value — uninterested in writing. Periodically, they burst into laughter. If you overheard a snatch of the conversation, you’d realise that the subject of mirth was writers who weren’t in their company. Their anecdotes proved the truism that every second writer is a fool.

I must say two things here. First, this story is from a long time ago. Twelve years have passed since the 60th anniversary of Independence brought us together in a strange foreign city. I’m using both adjectives despite the fact that a foreign city is bound to be strange because Frankfurt is stranger than most. If it had city-like characteristics (the poor; the working class; cafes; bus shelters), we — made to gather in the lobby; then herded off in groups to do readings — were kept from them. I saw little of Frankfurt and a lot of the writers.

The other thing is that the story is fictional. There may be a skeletal correspondence with an event that’s elapsed, but the tissue is fiction. The writers in it don’t exist. Their namesakes might, but they’re as independent of the “characters” I’m about to introduce as they are from their other namesakes. For instance, there may be many Javed Akhtars in the universe. They’re not to be confused with the one I spotted in the lobby, who shouldn’t be confused with the lyricist of the same name.

*

I say “long time ago” because 12 years is a long time in the life of a nation. Our country’s achievements at the time, its stupidity, its misguided ventures (of which the railway platform-like congregation in the hotel lobby could be counted as one), its generosity, its self-serving disagreements — all these seem as unreal now as frictions and friendships developed over a holiday. Some of the writers — Mushirul Hasan, Girish Karnad, Ananthamurthy, Dilip Chitre — are dead. Others may be in a state of siege.

The longstanding tension that simmered in the lobby — between those who wrote in Indian languages and the ones who wrote in English — still rankles, but — like people and misunderstandings that belong to a vanished world — also makes me smile. There was mutual contempt between the camps, and inequality — but no violence. Barring a few national figures, I preferred the bhasha writers. They comprised the old artistic order; we, the new social order, for which there was no “art” — only “nation”. We had breakfast together; one camp paid obeisance to the other, then moved on, since there was nothing to be gained by being in their company.

*

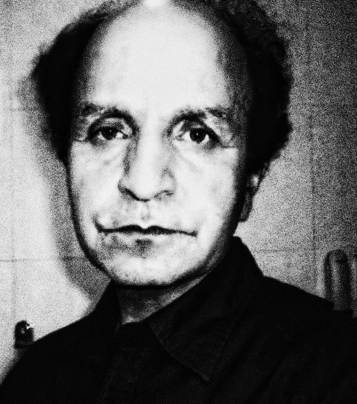

Among those I met was a small, suited Kashmiri poet called Shafi Shauq. The term “Kashmiri poet” carried a mild voltage. I was speechless for an instant, then said, “Hello!” Not that a Kashmiri poet is an impossibility, but that Shafi Shauq represented a concatenation of impossibilities, to do with his presence here, with a resolution to the problem being found, and peace ever being regained. I wanted to study him closely and ask him for forgiveness. He was diffident, as non-Anglophone writers — especially poets — are. Kafka-like, he’d adopted the guise of normalcy — I mean his twentieth-century appearance, the black suit, meant to sidestep attention. He was fair; his eyes shone gently. He had lost hair, like a Jewish intellectual. Keep in mind that he is a character in a story. There is a Kashmiri poet called Shafi Shauq, who’s very different, as this photo bears out:

We spent some time in proximity to each other, as writers were driven in vans to buildings to read in different rooms. The Germans had developed a taste for chaotic self-regard; they sat in unprotesting groups. Anyway, even if Mr Shauq and I had liked each other (which we did), what could we have talked about? I had examined him for signs of past explosions (any tell-tale residue on his jacket) and was relieved he was more intact than I was. I was also disabled by my sense that he’d lived, while I hadn’t; that writers in English, to make up for not having lived, must be relentless spokespersons. My love for Shafi Shauq was real, but we exchanged few words. Still, I went discreetly to one of his readings. He was mumbling into the mike, and then every few seconds the lines were repeated in German translation. The small audience was cowed into silence, either by the theme or the Frankfurt Book Fair. I still have the handouts with the English versions of the poems he read out.

Carthage

If there’s a paradise on earth, this is it.

He repeated ‘this is it’

three times, because once wasn’t enough

to dispel doubt. The first time he muttered

to himself, the second

and third declamations were to the world.

The exhortation reached Roman ears.

Carthage no longer stands.

The second poem is from the same page, just under ‘Carthage’.

Crossing a Street

Crossing a street, I lower my head

in case of danger. Sometimes, it’s something’s

absence I sense — nothing as tangible

as rocket or gun. I must be careful.

I cross the street, to find the house

where I’d expected it to be not there. I look

around in case I’m in a new neighbourhood.

Easy to lose your way.

It’s easy to lose your way at home,

to cross the street and never look back.

I lower my head instinctively

to protect myself from what I can’t see.

*

What struck me weren’t individual phrases — I couldn’t judge the translation — but the absence of overt politics, the lack of specific contemporary references or of protest. What’s stayed with me — reconfirmed as I revisit the page — is the poet’s lostness, his unsureness about the world.

*

Something happened the next day which became a matter of discussion in the lobby. We heard Shafi Shauq had gone out for a walk; he’d discovered a bridge. When he was on it, he saw a man in uniform approach him from the opposite direction. The man asked to see Mr Shauq’s papers, and then demanded to have a look at his wallet. Once he had the wallet, he made off with it.

*

We were scandalised. Is there no free country for a Kashmiri? To be ambushed here of all places! Might the terrors of home have a familiarity that you feel safer negotiating than an encounter with a stranger? Shafi Shauq seemed out of sorts, but he smiled. He looked like he wanted to go back. Liberty had begun to feel inimical. But go back to what?

*

No more was achieved at the Frankfurt Book Fair than at a family wedding. There was the same unfocussed jubilation and aimlessness. As in a phased mass migration, we were put on trains to Brussels. Some people arrived earlier, some later. It depended on when your panel was scheduled. Brussels had decided to take advantage of the large contingent at Frankfurt and, in the Book Fair’s aftermath, host its own extravaganza. Western Europe was showing signs of an “Indian culture” contagion. Who were we to argue with our role in the epidemic?

*

My panel was the next morning, with writer and diplomat Pavan Varma, poet and lyricist Nida Fazli, and another well-known Hindi poet whose name I have forgotten. We were supposed to start at 11, but heard that Nida Fazli and the other poet hadn’t reached Brussels. At 11.30 am, Pavan Varma and I were told to hold the fort, and we embarked on a variant of the debate — common to festivals at the time — to do with whether or not writing in English was a betrayal.

At 12.30 pm, Nida Fazli and the other poet walked in, heads bent, silent, like escapees from a calamity. Pavan, who was also a translator au fait with Hindi and Urdu literature, leapt up when he saw them. They greeted him gravely, and occupied the chairs left empty for them. Nida Fazli, in a patient, wounded voice, informed us of the reason for the delay. He and the other poet had been received at the station by festival volunteers. They’d been taken to a car, their luggage loaded in the back. Just as they were about to be driven off, a man knocked on Nida Fazli’s window and told him that there was something wrong with the rear bumper. Nida Fazli got out to have a look. The driver urged him to get back in immediately: the station was full of pickpockets. A little while after they’d finally set out, Nida Fazli found that his passport, money, and a notebook of unpublished poems had vanished from his overcoat pocket.

“I don’t care about the money,” he told us. “Money will come and money will go. It’s the loss of the notebook I can’t get over.” People made consoling remarks.

“They have no use for the notebook. You may get it back.”

“A passport was once found in a garbage bin.”

Express photo by Shuaib Masoodi

Express photo by Shuaib Masoodi

Without preamble, Nida Fazli plunged into a poem — interrupting himself only to say: “Those were dark days in Bambai! Human being had turned on human being”; we knew he was speaking of the riots at the end of 1993, when Muslims, terrified by the toppling of the Babri Masjid (“ab gira!” Uma Bharti had shouted as she’d struck a blow), were punished in Bombay for being terrified — “Dark days had descended and there was no light! And then one morning in the midst of that violence I saw a child getting ready as usual for school and I thought: There is still light! There is a tomorrow!” So addressing the audience, he resumed:

हुआ सवेरा

ज़मीन पर फिर अदब से आकाश

अपने सर को झुका रहा है

कि बच्चे स्कूल जा रहे हैं

morning comes —

again, the sky

lowers its head

towards the earth in salutation

because the children are going to school

Rising from his chair and looming over us in his long kurta, he repeated the verse, in the slightly irritating looping manner of Urdu and Hindi shairi, where tension is built up by retracing a path.

*

in order to bathe in the river, the sun,

wearing a turban

of gold malmal,

is standing

on one side of the road, smiling

that the children are going to school

*

Each verse was doubled, trebled, its span expanded, and money, notebook, and passport were placed in abeyance. Great bereavement and optimism converged. Is it the lot of those who have been besieged to recurrently relive their past? Is it worse to be a visitor without a passport or in a home where you have no status? Do we falter terribly without the birthplace that threatens us?

Coda

All this is from a long time ago. I was reminded again of the theft of Shafi Shauq’s wallet in 2014 or 2015 while I was teaching a creative writing workshop in Kolkata. Among the participants was a young Kashmiri writer called Asiya. She’d come from Baramulla on the recommendation of a well-known novelist. She was shy and, when she thought she was out of my sight, effervescent. She composed vivid accounts of her small town.

The participants, of course, went off exploring the city in their spare time. On one of these excursions, a tiny misadventure was averted. The details have become hazy: I had to get them corroborated by Asiya. In itself, the anecdote may not be worth repeating. It was reported to me by Flavius, a French participant, before one of the classes began. “We almost lost Asiya yesterday!” he said. “Lost?” I asked. “What do you mean?” Asiya was standing next to him, diminutive, dramatic, shaking her head in denial. “We were in the metro going to Park Street. We wanted to walk from there to Victoria Memorial. We’d got off the metro when, suddenly, the doors closed before Asiya could get off.” “Is that right?” I asked Asiya. “Oh but,” she exclaimed, “then the doors opened again! He’s exaggerating, sir. You should know Flavius by now! It was a temporary technical fault.” Asiya tells me that I then said (I don’t recall my exact words, but I know I said something of the kind): “You Kashmiris tend to get into trouble outside Kashmir.” She laughed loudly, as if at an observation that was not only absurd but incontrovertible. I then told her that Shafi Shauq had had his wallet taken from him in Frankfurt. “Do you know him?” I asked. She said she did: after all, she’d already written a book of poems in English — Asiya is part of Kashmir’s literary terrain.

She attended two workshops, returning to Kolkata in 2015. Maybe she liked the experience. I later met up with her in Delhi, when I told her of my longstanding plan to write a story about the depredations Kashmiris face when they’re placed in an environment in which unhindered movement can take place. “It will be about Shafi Shauq,” I said, “but not the actual Shafi Shauq.” “You must!” she cried passionately: I wonder if she had doubts in retrospect.

I had a chat with her on the phone when she was in Delhi last month, to ask after things that have no direct relation to this story, but which had to do with unfolding events. Communicating with her — on Messenger or by email — has become out of the question when she’s back in Baramulla. My sketch isn’t reliable as there are several facts I can’t check up on. Nida Fazli died about four years ago of a heart attack. Shafi Shauq, like most Kashmiris, is out of reach.

2nd December 2019

(Note: The poems by Shafi Shauq have no existence outside this narrative)