NEW YORK: In January 2017, days after President Donald Trump moved into the White House, Justin Connelly was at his home in Washington, bemoaning the fate of scientists.

He wondered: Would scientists resort to using chisels and stone to preserve their findings? Or, perhaps, stitch them into tapestries?

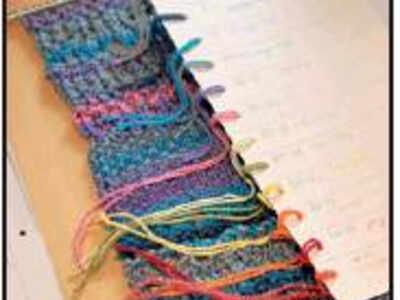

Connelly’s friend, Emily McNeill, worked in a knitting store. The two decided (along with Connelly’s then wife, Marissa) to assemble a kit of coloured yarns that knitters could use to create scarves that documented local temperature changes all year.

They would access data reported by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which knitters would represent in colours from sunny yellow to fiery red and icy blue. Connelly and his colleagues called the endeavor the Tempestry Project and, since then, they have sold more than 1,500 kits worldwide.

“We didn’t want this data lost forever,” he said.

Temperature scarves, as they are commonly called, have more than fashion appeal. Laura Guertin, a professor at Penn State Brandywine, Pennsylvania, uses hers as a teaching aid in the classroom.

So far, scarves have been knitted on behalf of 30 national parks, she said. Even Larry Fink, the chief executive of the investment firm BlackRock, recently wore a temperature scarf at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, to call attention to the climate crisis.

No one can pinpoint exactly when the first temperature scarf emerged but many knitters point to the popularity of the “sky scarf ” in the early 2010s.

Lea Redmond, a conceptual artist from Oakland, California, began knitting scarves in 2011 that reflected the weather. She did not intend it as a political statement on global warming but a reminder to appreciate nature.

In 2017, Guertin was inspired to crochet temperature tapestries to share with her students after seeing a quilt on Twitter. She now crochets baby blankets for friends, chronicling the daily temperature of a newborn’s first three months.

He wondered: Would scientists resort to using chisels and stone to preserve their findings? Or, perhaps, stitch them into tapestries?

Connelly’s friend, Emily McNeill, worked in a knitting store. The two decided (along with Connelly’s then wife, Marissa) to assemble a kit of coloured yarns that knitters could use to create scarves that documented local temperature changes all year.

They would access data reported by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which knitters would represent in colours from sunny yellow to fiery red and icy blue. Connelly and his colleagues called the endeavor the Tempestry Project and, since then, they have sold more than 1,500 kits worldwide.

“We didn’t want this data lost forever,” he said.

Temperature scarves, as they are commonly called, have more than fashion appeal. Laura Guertin, a professor at Penn State Brandywine, Pennsylvania, uses hers as a teaching aid in the classroom.

So far, scarves have been knitted on behalf of 30 national parks, she said. Even Larry Fink, the chief executive of the investment firm BlackRock, recently wore a temperature scarf at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, to call attention to the climate crisis.

No one can pinpoint exactly when the first temperature scarf emerged but many knitters point to the popularity of the “sky scarf ” in the early 2010s.

Lea Redmond, a conceptual artist from Oakland, California, began knitting scarves in 2011 that reflected the weather. She did not intend it as a political statement on global warming but a reminder to appreciate nature.

In 2017, Guertin was inspired to crochet temperature tapestries to share with her students after seeing a quilt on Twitter. She now crochets baby blankets for friends, chronicling the daily temperature of a newborn’s first three months.

Download The Times of India News App for Latest World News.

Coronavirus outbreak

Trending Topics

LATEST VIDEOS

More from TOI

Navbharat Times

Featured Today in Travel

Get the app